The Gift of South Dakota

Subscriptions to South Dakota Magazine make great gifts!

Subscribe today — 1 year (6 issues) is just $29!

Herbert Hoover, The Historian

Editor’s Note: Herbert T. Hoover, longtime South Dakota historian and professor of history at the University of South Dakota, died on March 21 at age 89. This story, written by fellow South Dakota historian Jon Lauck, appeared in our November/December 2007 issue.

In the spring of 1973, newspapers across the country carried reports from the Pine Ridge Reservation in western South Dakota, from the village whose name recalled a tragic episode in our nation’s history: Wounded Knee. More than 200 activists, led by members of the American Indian Movement, occupied the town and held law enforcement officials at bay. South Dakotans had watched from the sidelines as riots convulsed America’s big cities during the 1960s. Wounded Knee brought those troubles home.

|

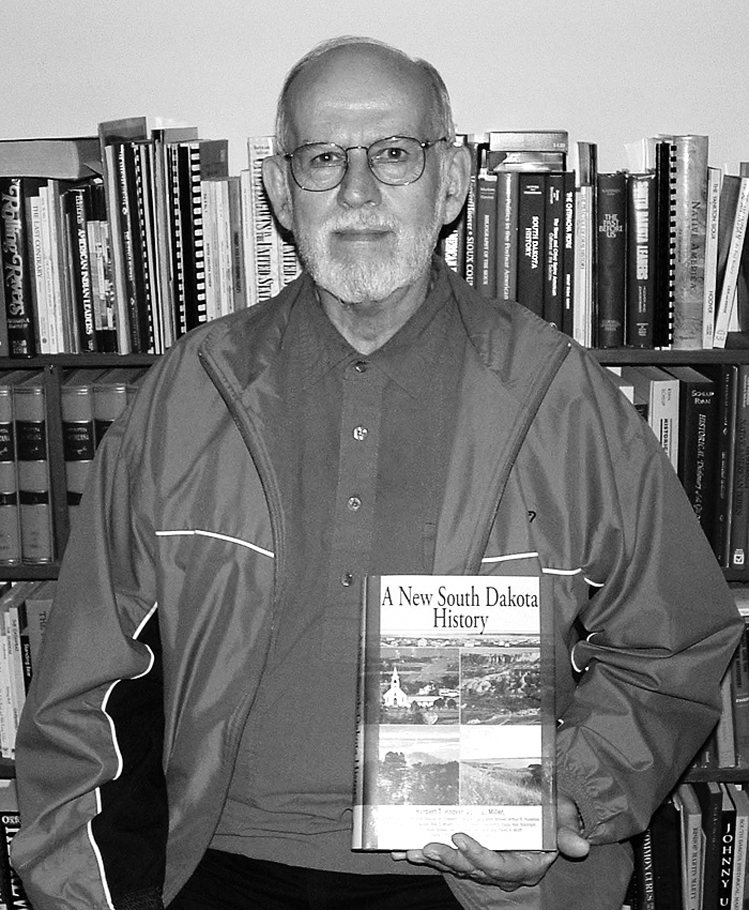

| Herbert T. Hoover taught for four decades at the University of South Dakota and became one of the state's premier historians. He provided an introduction and five chapters to A New South Dakota History, published in 2005. |

Few people outside the law enforcement perimeter could relate to those inside as well as Herbert T. Hoover, a professor of history at the University of South Dakota. He learned of the planned occupation beforehand, while participating in a sweat lodge ceremony at St. Francis, and lent both monetary and ceremonial support to the effort. Once the occupation commenced, he was invited into the village, where he participated with tribal leaders in traditional ceremonies.

Later, when AIM leader Russell Means was on trial in Sioux Falls, Means announced he might go down to Vermillion and take over the University of South Dakota. His threat was a joke, apparently, but in the wake of Wounded Knee, and given South Dakota’s racially tense atmosphere at the time, people took him at his word. Police and highway patrol officers took up positions around the town.

Because of Hoover’s experience and credibility with AIM, USD President Richard Bowen called upon him to help manage the situation. When Hoover went to find his history department colleague, Joe Cash, at the USD Oral History Center, he discovered just how seriously the other professor took Means’ words: Cash had a pearl-handled revolver on the desk in front of him.

“They will never get the oral history collection,” Cash said grimly.

Hoover’s response was, “Get real, man.”

No one ever did try to occupy the USD campus, but Herbert Hoover’s involvement underscores the role he’s played in some of the most significant, highly-charged episodes in Indian affairs of recent memory. He has been rightly recognized for his many years of work chronicling Indian history, but he’s lived it as well.

In 2006, after more than four decades teaching South Dakota history, Herbert T. Hoover retired from the USD history department. All those who care about the history of South Dakota should know Hoover’s story. He is part of an elite group of historians who have delved deeply into our state’s past; their work, hopefully, will help us better understand South Dakota’s present and future.

What is most immediately striking about Herbert Hoover is his name, particularly for those who lived through the Dirty Thirties, the most traumatic decade in South Dakota’s history. When Hoover’s parents named him in 1930, Herbert Hoover was still a Midwestern hero, a small-town Iowa boy who became president. They weren’t alone: the Hoover Library in West Branch, Iowa, has 13 folders of letters from Americans who wrote to President Hoover and proudly announced they had named their sons after him.

Hoover’s middle name is Theodore, after Theodore Roosevelt. With such namesakes his passion for American history was virtually guaranteed. After the Great Crash of the American economy in the 1930s, and the staining of President Hoover’s reputation, our Herbert Hoover wisely chose to go by the name “Teddy” until the animus against President Hoover passed.

Hoover was raised on a farm in Wabasha County, Minnesota, which is also the home of Eugene McCarthy. Hoover’s mother, a school teacher, instilled a love of books in her young son. He attended Plainview High School, then went on to the University of Minnesota. After his studies were interrupted by service in the Marine Corps during the Korean War, Hoover returned to UM as a more serious student and completed the requirements for a degree in chemistry. Hoover preferred history, however, and quickly abandoned the “dull” life of being a pharmacist. He enrolled at New Mexico State University and in 1961, earned a master’s in history.

In graduate school, Hoover turned to the history of the American West. That wasn’t a cutting-edge field at mid-century, but by the 1970s Western history was booming. After finishing his master’s thesis, he moved on to the Ph.D. program at the University of Oklahoma, which was known for its study of American Indian history. His Ph.D. advisor was Eugene Hollon, who was himself a student of Walter Prescott Webb. (Students of the history of this part of the United States will recognize Webb as the author of The Great Plains, a seminal tract published in 1931 that is still in print.)

While at Oklahoma, Hoover came to know another famous South Dakota historian, Gilbert Fite, who was beginning his career in the University of Oklahoma’s history department. (Fite’s first book, Prairie Statesman, a biography of South Dakota governor Peter Norbeck, was recently reissued by South Dakota State Historical Society Press.) Fite helped set Hoover on his path to a lifetime of teaching South Dakota history. In 1967, long-time USD historian Herbert Schell was reaching mandatory retirement age. Fite, who had studied under Schell as an undergraduate at USD, recommended Hoover to the university.

As the years went by, Hoover’s courses at USD increasingly focused on American Indian history, one of the most explosive areas of historical research in recent decades. Hoover’s great interest in the history of the Sioux was complemented by the large body of work generated by other historians. Hoover once noted that, “no other province in the United States ever attracted greater attention,” than that claimed by the Sioux. In the recently released A New History of South Dakota, to which he contributed the introduction and five chapters, Hoover wrote that the Sioux have garnered more international attention than any other tribe, in part due to their famous resistance to white encroachment. “You couldn’t push the Sioux around,” Hoover says. “They never lost a battle against the U.S. Army.”

Hoover’s interest in the Sioux stems in part from his own Indian heritage. His father was part Ioway, the tribe which gave the state its name. “I was always the dark guy in the school picture,” says Hoover. “Every time I got in trouble they would say it was that Indian blood.” He endured much less than other Indians because of his heritage, says Hoover, and in later years it was “a marvelous asset” in his professional development.

Hoover helped spur scholarly interest in Indian history with his published writings and research work in archives and library stacks. These professional interests also positioned him to appreciate what he terms the “Indian renaissance” of roughly 1965-85, when traditional spiritual ceremonies and cultural practices that had been driven underground were revived on the reservations.

Hoover’s interests and academic position made for a unique opportunity. Several of the movement’s leaders asked if he would host traditional ceremonies on his farm near Vermillion, which would give Indians in the east and whites alike a chance to learn about and participate in them. Hoover built a sweat lodge and environment for the sacramental use of peyote on his farm. “I had to be careful of the peyote church, because the FBI was creeping around,” he recalls.

As a lodge keeper, Hoover came to know many medicine men, “who wanted to educate the people of South Dakota about the fact that they weren’t a bunch of heathens, or pagans.” Indian leaders, including members of the American Indian Movement, also took part in the ceremonies. Hoover’s involvement with AIM and his research on American Indians unfolded against the backdrop of growing Indian activism in both the nation and South Dakota, creating a unique fusion of academic standing, experience with traditional Native culture, and first-hand knowledge of a burgeoning social movement. “That farm made things out of my career that I could not have made any other way,” Hoover says.

Hoover’s experience and years of study have made it possible for him to begin work on his next book, a history of the American Indian renaissance. Many of Hoover’s photographs from the days on his farm and the period of the Indian renaissance are currently being placed at the Center for Western Studies, on the Augustana University campus in Sioux Falls.

Hoover also became involved in a famous murder trial during his early years at USD. In the late 1960s Baxter Berry, a West River rancher and the son of former governor Tom Berry, shot and killed an Indian who was trespassing on his ranch. Berry was acquitted of murder charges but ended up suing NBC News for defamation for the story they ran about the shooting. When Hoover testified for NBC, he was accosted on the steps of the courthouse in Pierre by one of his university students who sympathized with Berry.

While at USD, Hoover also began writing for encyclopedias, and, with the aid of a grant from the Doris Duke Charitable Foundation, he began collecting oral histories of Indians on all of South Dakota’s reservations. Hoover interviewed over 750 people and deposited many of the interviews in an archive at USD. With the help of a National Endowment for the Humanities grant, Hoover also completed a study of Indian-white relations in Sioux Country. For South Dakota’s centennial, Hoover organized a book of essays entitled South Dakota Leaders, which chronicled the lives of prominent South Dakotans.

In one of his greatest accomplishments, Hoover collected two bibliographies of publications about South Dakota, one of which was completely dedicated to the history of the Sioux. After countless days “in dusty archives and libraries across the United States and Canada,” Hoover compiled and annotated a list of 4,614 sources relating to South Dakota history.

That experience caused Hoover to realize there is no “state in the history of the West that has received as much attention from legitimate scholars.” With good reason, he says. South Dakota has been favored with what he deems exaggerated diversity, a mix of races and nationalities that few other states can match. Compared to South Dakota, the history of neighboring states “is really dull.”

Hoover thinks that the production of books about South Dakota could have been larger, however. USD’s master’s degree program in history should be complemented by an equivalent program at South Dakota State University, he says. He also believes the state is limited by the lack of a Ph.D. program in history, one which could promote historical research on South Dakota. Even so, Hoover opposes the creation of such a program without a substantial increase in the size of the history departments at the state universities, additional funding or the merger of the state’s largest universities.

Hoover is not afraid to break with conventional wisdom and ruffle feathers. Despite his great respect for Indian culture, he believes that Indians are as much to blame as whites for any remaining racial enmity between the two groups. On another matter, he thinks tribal governments desperately need a civil service system because, “every time there is a turnover in the presidency or tribal council, everybody gets fired,” causing political instability on Indian reservations.

Hoover also believes that the disappearance of “legitimate medicine men” has created a vacuum of spiritual leadership in Indian Country. The political and spiritual problems on the reservations today represent a step backward from the revival years of the 1970s. “The renaissance gave Indians a chance,” says Hoover, “but they are losing it.” In his next book, he hopes to explain what went wrong.

After many years in the trenches of South Dakota history, Hoover joins the pantheon of the state’s great historians, which includes Doane and Will Robinson, George Kingsbury, Herbert Schell, Howard Lamar, Gilbert Fite, Lynwood Oyos, Gary Olson and John Miller. Never afraid to speak his mind, Hoover plans to continue his writing regimen and his contributions to South Dakota’s historical corpus. His coming history of the Indian renaissance will not pull any punches, he promises. He will not spare Indian leaders the failures he’s seen in Indian country during recent years.

Yet Hoover is unafraid. “I mean, who’s going to knock off a 77-year-old man who wears glasses?”

Comments

Working with Dr. Hoover and his children helped me become more aware of the challenges of living is SD and about being of Native American heritage in the area. Dr. Hoover and his family changed my life as a teacher and positively influenced my views more than anyone in my professional background. To live in South Dakota should require a knowledge and understanding of the Native American history here , of which he is a vital part..