The Gift of South Dakota

Subscriptions to South Dakota Magazine make great gifts!

Subscribe today — 1 year (6 issues) is just $29!

The Little Giant of USD

Editor’s Note: Bill Farber died in Vermillion in March 2007 at the age of 96. This story is revised from the July/August 2005 issue of South Dakota Magazine. To order a copy or to subscribe, call (800) 456-5117.

|

| Bill Farber taught political science at the University of South Dakota for 38 years, and mentored many of South Dakota's most successful people. |

The small man with the mighty legend prefers his brown recliner just inside the front door of a small house across the street from the University of South Dakota campus.

It’s been Bill Farber’s favorite spot for years. His call, “Come in!” has welcomed students and politicos, dreamers and those who needed a firm kick. Set to celebrate his 95th birthday on July 4, Doc, as many of those students still call him, has become a living history lesson whose hand has moved behind the scene for decades in South Dakota, but whose reach has extended far beyond our borders to tackle questions of international cooperation.

When I was asked two years ago to help Doc write his autobiography, I had no idea how many lessons he still had left to teach. They’re the ones rooted in history, the ones we’re doomed to repeat unless we pay attention.

We began in March 2003 with a transcript of interviews from nine years earlier. We began with Doc’s dream of writing his autobiography from those transcripts. We began believing my job would be to write, rewrite and massage. Instead, we — Doc, political science secretary Mary Smart and I —embarked on a treasure hunt that became that history lesson.

The basement was our Shangri-La. A trip downstairs suggests Doc never threw out a piece of paper that crossed his desk, mailbox or any conference table at which he sat. Minutes and agendas — often multiple copies — from meetings held everywhere from Vermillion to Paris for the last eight decades. Letters to Doc and from him. Speeches and bits of speeches mixed with copies of the high school newspaper and yearbook he edited, old report cards, college papers, reports and research material.

The basement yielded treasures, but none so good as the day Doc wondered what was in the battered suitcase under another tall pile of papers. Inside, we found the letters he’d sent home from World War II and asked his mother to save. We also found letters he’d sent from Korea when he was setting up a school of public administration.

More than two years later, Footprints on the Prairie is due from the publisher this month (July) in time for Doc’s birthday celebration. At nearly 95, nothing seems to quench his interest in the world. Maybe to the chagrin of administrators and lawmakers, nothing can stop the endless flow of suggestions to improve government.

Just this spring, as committees discussed how to revitalize the legislature, Doc suggested that lawmakers meet quarterly, so they could deal with problems continuously through the year. Bills could be introduced in one session, adopted the next. Legislators could take advantage of what’s being done in other states.

Since money has always been a problem for state government, Farber also suggests adding 2 percent to everyone’s federal income tax returns and designating the revenue for health and education. “It’s simple,” he said.

|

| A believer in travel and public service, Farber served in the Air Force at Hickman Field in Hawaii. |

His rallying cry for more laws to encourage government consolidation in a state with few people never ends. “We need to do some bold thinking and not be afraid of experimenting,” he said.

The broad outlines of Doc’s story have often been told. He was hired to teach government at USD in 1935, and long before he retired as department chairman in 1976, he had become a force to reckon with. He’s still tickled that his July 4 birthday — just after the cutoff — meant he could teach until he was almost 66, instead of the previously state-mandated 65.

Here is the rare man who practices what he preaches. He believes in teaching and in public service. He helped establish South Dakota’s Legislative Research Council, and worked for constitutional revision, home rule, and single-member legislative districts. Besides the school of public administration in Korea, he helped set up an international training program for public administrators in Bruges, Belgium.

And he taught, his students becoming his family as he challenged them to do more than they thought they could. Among others, he prodded Tom Brokaw and Pat O’Brien — arguably the state’s best-known television personalities — out of college failure.

“His influence reaches well beyond the courses he taught in political science or the forums he organized, the research projects he supervised and the papers he graded,” Brokaw wrote in the introduction to Footprints. “Bill was a life force on campus, a roly poly energy cell constantly encouraging students in his department and others to look beyond the horizons of the Great Plains, to take their place in the wider world as well as in their home towns and counties across the prairie.”

At Farber’s retirement dinner, O’Brien remembered: “Doc and I talked about the fact that he is setting people up in life all over the country. He said to me, ‘I feel like the playwright sitting in the balcony looking down on stage at all my creations.’ I must say this playwright has had more success than Shakespeare.”

Besides that noteworthy duo, Farber mentored Rhodes and Fulbright scholars, and his students run multinational corporations, teach at the nation’s largest universities, run for political office and write books.

Most of Doc’s protégés are men. Mary Lynn Myers, one of the few exceptions, said there weren’t many women political science majors in her era. Besides, many of the men Doc mentored were those who were dropping by the wayside, she said. “Young women didn’t do that very often.” Women had to be smart, determined and wear thick skins if they went into political science.

Farber’s house is packed with miscellany from around the world. A Korean screen was a gift from a grateful father after Doc wrote a tuition check for the son. Doc’s dad started the collection of barber bottles. And there are books and photographs, more photographs than anyone would want to count.

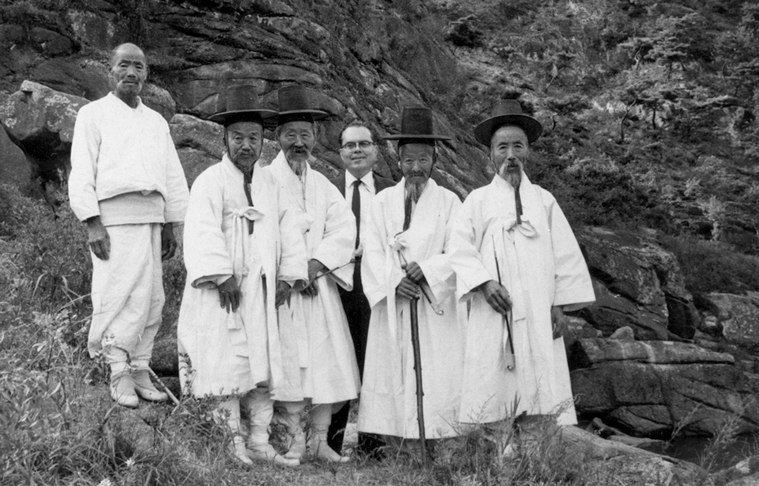

|

| In the 1950s, Farber helped to establish a school in South Korea and was pictured with a group he called, "five wise men." |

Bill Farber, the legend, is a small, portly man with a deceiving twinkle in his eye. He knows what he wants, and he usually gets it. The story began July 4, 1910, the day Doc was born but not breathing. The doctor swished him between hot and cold water and slapped him on the buttocks to make him cry. As Doc wrote in the book: “Some might suggest that from that point on I have never ceased to express myself in emphatic terms.”

Doc’s South Dakota accomplishments are well known. When racial equality became an issue in the courts and on the streets, Doc helped found the Institute of Indian Studies at USD, which brought tribal leaders together to talk about challenges they faced. When state senators and representatives saw the need for better information, Doc pushed and helped organize the Legislative Research Council. But his eye has never been confined by the state line.

In the two years we worked together, America invaded Iraq. Farber had lived through and helped shape national and international policy during the Cold War; he believed then, and he believes now, there’s no reason to go into combat. “Footprints” doesn’t dwell on war and peace, but the times threw war in our faces.

Doc has believed in a global community since he was president of the international relations club at Northwestern University during the Depression. He still remembers the German speaker who predicted that war would come, and Germany would be blamed. He does not excuse Hitler, but he says the economic roots of World War II were fostered by greed in countries like the United States.

When war broke out in Europe a decade later, Farber was teaching at USD. What many have forgotten is that this country was largely isolationist in the 1930s. In 1940, Doc debated against Roosevelt’s lend-lease deal with Britain, believing it would draw America further into the war. He taught a Sunday school class for young men who knew they would have to go.

At 30, he asked a local minister whether a Christian could kill, even in military duty. The minister preferred not to answer. Today, Farber still feels guilty he wasn’t a conscientious objector. “I just didn’t have the guts,” he said.

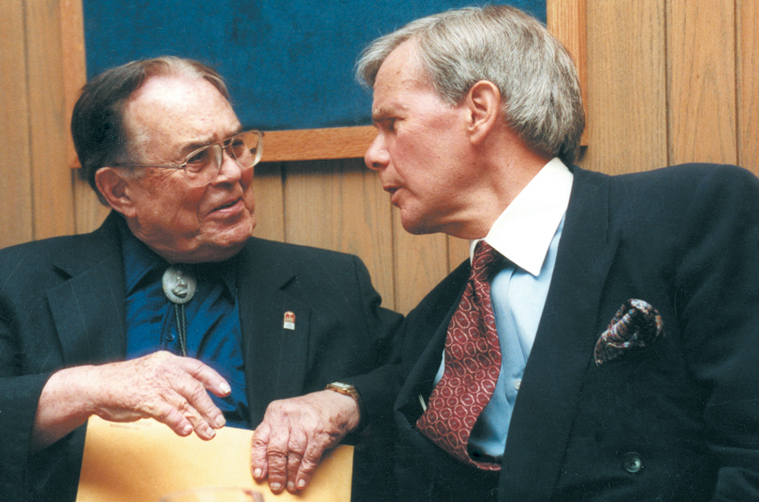

|

| Farber advised a young Tom Brokaw to quit college until he was done partying. Brokaw returned to campus with a better attitude and the rest is broadcast journalism history. |

As a political scientist, Doc watched the war propaganda machine spring into motion, and he remembered how British propaganda had deceived America during World War I. Viscount James Bryce, an author of a well-used American government textbook, verified that Germans had killed Belgian priests, then hung them, heads down, as bell clappers. Knowing Bryce, the American political scientists supported war. Doc wrote: “Evidence after the war, however, showed the Germans had not massacred the priests. When confronted by the political scientists, Lord Bryce said he wanted to save as many English lives as possible and thought his report would help if it convinced Americans to get involved.”

Doc lived through war pricing and rationing, and his basement yielded sheaves of letters to merchants and manufacturers. A Des Moines manufacturing company learned how to set South Dakota prices for salad dressings; the Watertown War Price and Rationing Board was not allowed to add an extra charge for sacking sugar; an Iowa café was allowed to raise its milk prices.

At 33, Doc was drafted and spent the next three years in the history division of the Army Air Force in Texas, Hawaii and Guam. At one point he convinced Vermillion’s George Johnson to carry his 80-pound barracks bag because it was too heavy and his shoulders too small. When it came to marksmanship, he wrote home: “As you can guess, I am the class dumbbell on most of these outdoor things, and the corporal has a worried look every time he glances in my direction.”

The warrant officer test also proved a challenge: “I’ve only rarely been able to chin more than once — one jump up, then down. I knew I couldn’t do it until a guy asked me if I was really stupid enough to want to go overseas. When I said yes, he grabbed me around the knees and pushed me up 10 times so I could qualify.”

Doc did not dispute that a country should go to war if attacked. But he could not stop questioning the why of sending young men into the Army. He wrote to friends in 1943: “The great tragedy of those in the army is, as I see it, in all the time that is being taken from real living. The tragedy is all the greater for those in their twenties. To see these alert young men being conditioned to army thinking and ways of doing things, and to the army type of social contacts is most discouraging. War is blight from which not many recover.”

|

| No university professor in South Dakota history has been accorded the honors of Dr. Farber on USD's Vermillion campus, where there is a Farber lecture series, a Farber scholarship fund and Farber Hall. An outdoor bronze of the genial prof was unveiled in 2002 on the university lawn near Old Main. |

From war, Farber learned to trust international organization; he’s convinced the 1945 formation of the United Nations should have eliminated combat. But he’s been discouraged. “Here we are again not seeing to it that the United Nations is the institution it ought to be,” he said recently. He’s convinced that the United States still does not understand the importance of international problems.

“We are all human beings on this globe,” he said. “We all ought to be concerned with the welfare of everybody on the planet.”

A dedicated traveler, Doc learned about fitting into another culture when he spent six months in late 1958 — just five years after the end of the Korean War — in South Korea helping set up the school of public administration at Seoul University.

The school hoped to train senior public servants to be more efficient and effective, so democracy would be more readily accepted. Doc writes: “In a country plagued by red tape, poorly paid personnel and duplication, our challenge was to adapt medieval society to the modern world overnight.”

In true Farber fashion, Doc half adopted a troupe of high school boys, helping them with their English, taking them out to eat and to see sites in Korea they would not see on their own because they had no transportation. And he learned.

“Very quickly one discovers … that that which one had thought of as being rather firmly fixed principles, may not be so firmly fixed at all,” Doc wrote in 1961. “One finds himself examining almost at once the fundamentals of his so-called science. Indeed, it goes much further than that, and one has some real questions to raise about things in the conduct of his own living that previously have been accepted without examination.” American representatives in foreign countries ought to be humble, Doc wrote, remembering an old Korean proverb: “Don’t speak too soon; wait and see.”

The lessons continued when South Dakota’s Sen. Karl Mundt asked Doc to be minority counsel for the Senate Subcommittee on National Policy Machinery, a committee charged with making government more efficient. In his first Washington stint, 1960-61, Doc studied New York Governor Nelson Rockefeller’s proposal that would allow the president to appoint a first secretary of government to reorganize the executive office and improve response to national security and foreign affairs — an idea Farber would still like to see implemented.

Although Farber left Washington when John Kennedy arrived, he still believes firmly in Kennedy’s words after the Bay of Pigs invasion was averted. “The world knows that Americans will never start a war,” the president said. “This generation of America has had enough of war and hate … . We want to build a world of peace where the weak are secure and the strong are just.”

“Unfortunately,” Doc wrote, “this century has proved Kennedy wrong. The current Iraq war shows we still must learn to make peace.”

Returning to Mundt’s service in 1965, Doc became the senator’s consultant to the North Atlantic Assembly’s Committee on Education, Information and Cultural Affairs. In that capacity he helped set up an international training seminar for mid-level government administrators. This was Doc doing what he believed in most: Training public servants to be the best they could be.

The North Atlantic Assembly assignment sat Farber across the table from Sir Fitzroy Maclean, a British representative, who already in 1966 predicted America would never win the Vietnam War. “The most important thing would be the propaganda effort with the people to get them to support you,” Maclean told Doc. “Americans think all they have to do is bomb the hell out of anybody and they’ve won. You can’t do it that way.”

Another message stuck.

Doc despairs at America’s inability to avoid war. “We ought to be better, and I am not confident, on the basis of our past record, that we can successfully avoid another major conflict — and that could well be the end of civilized society as we know it,” he wrote. His conviction has not changed.

After two years with Doc Farber, his vitality — even in his 90s — remains with me. I understood best when I told him I’d just turned 50. Doc’s bright eyes peered out from a Yoda-like face. “Well,” he said matter-of-factly, “then you’ve got another 50 to go.”

That’s when I understood Doc’s magic.

Comments