The Gift of South Dakota

Subscriptions to South Dakota Magazine make great gifts!

Subscribe today — 1 year (6 issues) is just $29!

Mountain-made Furniture

|

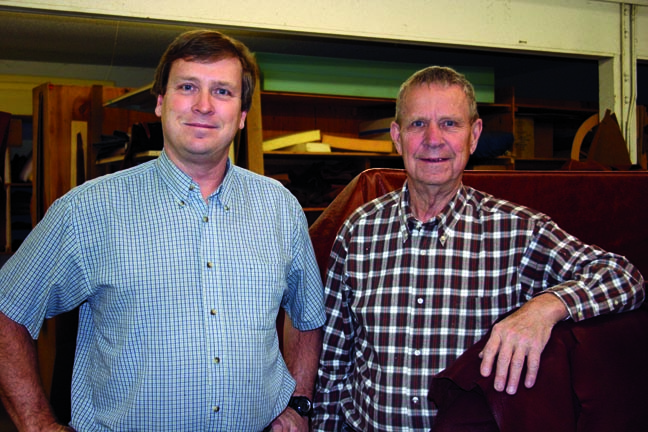

| Greg and Harold Stone in their Rapid City shop where they create over 200 pieces of buffalo leather furniture yearly. |

Step inside the Dakota Bison Furniture showroom and you’ll know instantly that you’re not in a generic chain store. The rich buffalo leather scent hints of the wild Black Hills. The sound of workers confirms that the furniture you see was built just a room away. That doesn’t mean the wingback chairs, sofas, love seats, and ottomans all stay in South Dakota. Greg Stone, the third generation of Stones to build furniture in Rapid City, says Black Hills aficionados from coast to coast buy the furniture. “I’d estimate we’ve shipped to 75 percent of the states,” he says. “But we don’t have our furniture in stores anywhere else. It’s like Black Hills Gold jewelry used to be. You can only buy it in the Black Hills.”

And every piece is handcrafted and one-of-a-kind. “Because of patterns in the leather, every piece is different,” notes Harold Stone, Greg’s dad. “Buffalo furniture would be hard to mass produce.”

Only a handful of furniture makers operate in the Hills. Not surprising for a region that has always nurtured individuality, most local builders are known for singular products or niche markets. While Black Hills furniture may be shipped anywhere, like Stone’s products, there’s a market close at hand: people who move to the region not so much for careers as for a Black Hills lifestyle. Furniture can be an expression of that lifestyle.

The first Stone to build furniture in Rapid City was Hans, a Norwegian immigrant who started in 1933. “Furniture building wasn’t something he brought over with him,” says his grandson, Greg. “He got started by doing upholstery work, and it was an evolution from there. When you do upholstery, it’s easy to start taking ideas from the furniture you work with and to develop ideas for building your own things.”

|

| A bedroom set by Perdue Woodworks in Rapid City. |

Greg says the basics of sofa or armchair construction are simple. There are mainly four wooden pieces: seat, back, two arms. Of course, cautions Harold, that construction had better be solid. “If you’re shipping it around the country,” Harold says, “and you’re worried the frame might not hold up, you’re in trouble.” After a frame is completed, the builder has decisions to make about springs and foam. Then the real craftsmanship comes into play in working with the surface material.

For more than 60 years the Stones took pride in high quality upholstered furniture with fabric or cow leather surfaces. Then, in the late 1990s, bison rancher Duane Lammers stopped in with some buffalo hide. Could the Stones build him a customized chair with that leather? They did, and while the chair was still in their shop, another customer wanted something similar. The little company was quickly transformed. “It was a nice thing to come along in the twilight of my career,” says Harold with a smile. “I was at the age where most people retire.” Instead he remains part of a production workforce of five, producing what’s been called “instant heirloom furniture.”

These heirlooms should survive a few generations, says Greg. He believes buffalo leather has about twice the durability of cow leather. Customers remark that they find the surfaces soft to the touch, and often they are drawn by the furniture’s oversize design — a Stone trademark.

More than 200 furniture pieces are made annually. “We’re small enough that we often get to know our buyers,” says Greg. “Some of them will come with photos of furniture they like, and ask us to make something like it using buffalo. We’re happy that very few come back to us with complaints. I guess you could say we like meeting our customers, and then not meeting our customers.”

|

| John English makes his own furniture and also teaches others the trade at the Black HIlls School of Woodworking. |

There’s not much exposed wood in a Dakota Bison Furniture piece. But an hour north of Rapid City John English creates — and helps others create — furniture that’s all about wood. He is one of South Dakota’s best-known woodworkers, building pieces and explaining exactly how he did so with readers around the world, usually in American Woodworker magazine. He’s authored or contributed to several books. Born and raised in Ireland, English realized his dream of living in the American West with his family. He isn’t fazed by the fact that most quality hardwoods for furniture grow in the eastern United States. English’s friend, Rod Schaeffer, trucks in walnut, cherry, maple, oak, and other varieties from Pennsylvania and English stores them in Spearfish.

“The Black Hills is mostly a softwood region, and that wood is used primarily for building construction,” English says.

To be sure, there are Black Hills woodworkers who build much-loved furniture entirely from Black Hills woods. That includes builders who like a knotty pine look and those who manufacture rustic log pieces. A South Dakota material English thinks deserves more respect than it gets is cottonwood. “Cottonwood has to be dried for five or six years,” English says. “I think it’s gotten a bad reputation because of people who cut it one year and try to build something the next.” Other local woods English likes for accent components in furniture are juniper, diamond willow, and Russian olive. “But you don’t want those woods for the main component, because they aren’t cut straight and won’t stay straight,” he warns.

Some of English’s furniture creations are sold at Gallery 97 in Belle Fourche, located on the ground floor of the old city hall building. Upstairs English runs the Black Hills School of Woodworking, where people make their own high-quality furniture (along with other wood creations).

“Someone walks in with a picture from a magazine, or something they drew on a napkin, and we show them how to use all the tools,” says English. “We put a strong emphasis on hand tools.”

About 40 percent of his visitors are women. End products have included dining room tables, cabinets, tall boys, toy chests, and much more. “Most people do three to five projects, and then they’re weaned, ready to work on their own,” English observes. The very best products may be juried and deemed suitable for display downstairs at Gallery 97.

|

| Eric Shell displays an oak table he designed and created at English's Belle Fourche school. |

That’s what happened to a stunning oak table created by Eric Shell, who lives at Upton in Wyoming’s strip of the Black Hills. The local oak Shell used is spalted. That means the wood began to decay when the tree died, and the slow process of decay resulted in random color streaks. “I like to take structured designs and blend them with natural materials to give my work a contemporary Western flavor,” Shell wrote in a placard displayed with the table.

Natural yet contemporary — if there’s a credo for the Black Hills’ most creative furniture makers, that may be it.

The bulk of mass-produced furniture Americans buy has traditionally come from the East Coast, where the hardwoods grow. In recent years Chinese products have claimed a big share of the market. A Rapid City company keeping 115 South Dakotans employed in these competitive times is Perdue Woodworks, producing particleboard and medium density fiberboard furniture. “We make competitively-priced bedroom furniture — chests of drawers, night stands, bookcases,” says Richard Perdue. His father, Don, started the operation in Montana in 1970 and moved it to Rapid City in 1987. Last year about 220,000 pieces of furniture were trucked to 3,000 retail outlets.

Dakota Textiles of Sturgis established an unusual market niche and is betting that its high industry standards will keep demand steady. The products: small upholstered sofas, easy chairs and ottomans that accommodate young children. The furniture pieces aren’t toys. They conform to the same construction expectations as their counterparts for adults. Workers with disabilities from Black Hills Special Services Cooperative work alongside non-disabled staff to build, pack, and load three-piece sets for shipping. That production arrangement began in 1987, and since then the furniture has gone to all 50 states and a handful of nations overseas. Much of it goes to day care centers, preschools and pediatric waiting rooms.

|

| Marlene Lawton and Thomas Vaughn put finishing touches on a piece of children's furniture at Dakota Textiles in Sturgis. |

“Right now we have seven fabric colors available,” says production coordinator Taylor Carlson, “and we’re willing to customize colors if someone wants to buy their own fabric.”

While people often call the miniature furniture cute, make no mistake. It’s also Black Hills tough with solid frames of locally harvested pine. “I saw one of our sofas fall off a moving pickup once,” recalls Bob Markve, who set up the production shop in 1987. “It bounced down the highway. We picked it up and the only damage was a little scabbing of the fabric.”

Recently a day care center brought back two Dakota Textile furniture sets for new upholstery after 16 years of daily use. In other words, the toddlers who originally climbed all over these sofas and chairs were off to college or into careers by the time the furniture started looking worn. “We rehabbed it for free,” says Carlson.

Good for another generation.

Editor’s Note: This story is revised from the March/April 2010 issue of South Dakota Magazine. To order a copy or to subscribe, call 800-456-5117.

Comments