The Gift of South Dakota

Subscriptions to South Dakota Magazine make great gifts!

Subscribe today — 1 year (6 issues) is just $29!

The Violinist and the Sculptor

|

| Ruth Ann Karlen has traveled across the country to research and preserve the nearly-forgotten history of a woman who contributed greatly to the Crazy Horse carving. |

Rapid City's Ruth Ann Karlen believes Dorothy Comstock Ziolkowski Moreton fell through the cracks of Black Hills history.

The two women never met, but Karlen sometimes feels as though Dorothy is sitting in the room with her as she reads decades-old letters. She routinely calls her research subject by her first name. She describes a woman who was an accomplished violinist, writer, world traveler, and force behind the establishment of Crazy Horse Memorial.

“Dorothy was the first wife of Crazy Horse mountain sculptor Korczak Ziolkowski,” says Karlen, who believes the world’s biggest carving might not exist without Dorothy’s early efforts. Karlen can paint a detailed life story, in part because Dorothy’s cousin turned over to her photographs, writings and other documents.

“I would have been happy with a shoebox of materials,” Karlen laughs. “Instead, I got the jackpot.”

And eventually more. Karlen’s investigation has taken her coast to coast, spurred by a graduate history course that she took in 2005 while working as a Rapid City public school librarian. The class stressed how educators can uncover significant history by seeking out primary sources. Karlen’s travels included Vassar College in Poughkeepsie, New York, where Dorothy graduated in 1919, and the campus chapel where Dorothy and Korczak exchanged wedding vows in 1934.

Like most women at Vassar a century ago (the all-female school wasn’t yet coed), Dorothy came from East Coast social standing and wealth. Her father was a highly respected surgeon at Roosevelt Hospital in New York City, and in 1905 he took his family on an ocean liner to the Far East — an incredibly rare travel opportunity. The trip was only part of Dorothy’s early international experiences. She lived in England for five years with her family, and after attending Vassar she moved to Paris to study violin with the renowned George Enescu.

Her trek into the interior of the American continent — specifically the Black Hills — can be traced to an encounter in Massachusetts after returning from France. She met Boston sculptor Korczak Ziolkowski, several years her junior, who later told Dorothy he was sometimes his own worst enemy because of his brash, gruff manner. Dorothy experienced that immediately. Trying to make small talk by telling Korczak she admired two New York sculptors, she heard Korczak scoff, saying that most sculptors he liked were dead, artists of previous centuries who cut images from stone rather than molding clay for bronze statues, as Dorothy’s New York artists did.

Korczak revealed great admiration for one contemporary American sculptor: Gutzon Borglum, who at the time was carving presidential likenesses from hard mountain granite in South Dakota.

Despite Korczak’s antisocial ways, and possibly somewhat because of them, too, Dorothy found herself in love with the young sculptor. The attraction proved mutual, and the president of Vassar himself participated in their wedding because of his friendship with Dorothy. She was 36, Korczak 26, both driven by artistic spirits. Dorothy would play with the Boston Symphony. Korczak always called her Dorrie.

“She was very much an East Coast, proper lady,” Karlen notes. “I’m not sure she owned a pair of slacks.”

|

| Korczak Ziolkowski and Dorothy Comstock were married in 1934. They adopted a daughter, Anne, and moved with Dorothy's mother, Bertha Comstock, to the Black Hills in 1948 as Ziolkowski prepared to begin work on Crazy Horse Memorial. The family is pictured above in January 1944. |

An East Coast lady, perhaps, only because she hadn’t yet experienced the American West. But five years after the wedding a dream position opened for Korczak: assistant sculptor under Borglum at Mount Rushmore for the 1939 carving season. Traveling to South Dakota by automobile in that year, of course, didn’t compare to steaming to Asia in 1905, but to some Easterners the adventure didn’t fall short by much. Dorothy’s writing documented the journey.

She described crossing South Dakota east to west — early summer croplands East River that looked like they could use rain, eerily fascinating Badlands and, finally, the splendor of the Black Hills, where they drove “up, up, up endlessly, into the dark pines which had been the sacred temples of the Sioux.” Dorothy called the Black Hills “mystic,” a region where, “anything might happen except the expected — and strange events lost their strangeness.”

For example, Dorothy and Korczak loved the area’s songbirds. Always attuned to classical music, Dorothy identified one “that repeated deliciously the theme of a Schubert Rondo!”

“We led the life of pioneers in Dakota,” Dorothy wrote to former Vassar classmates, “in a log cabin with porcupines, mountain lions, elk and rattlesnakes for company! Every day Korczak worked on the Mount Rushmore Memorial, as Borglum’s only sculptor assistant, and I spent all my dimes in telescopes, watching my only husband dangle on a tiny cable over the cliffs. In the studio below, I did publicity for Borglum, and I wrote a pageant, which was given there for the Golden Jubilee of the State of South Dakota.”

Dorothy’s pageant commemorating 50 years of statehood was part of the Theodore Roosevelt head dedication (each of the four Rushmore figures had its own dedication over the years). “Held on a Sunday evening, it was by far the best attended of all the Rushmore dedications,” wrote historian Rex Alan Smith in his 1984 book, The Carving of Mount Rushmore. Three thousand cars carrying 12,000 people showed up, and that number was dwarfed by a national CBS radio audience listening live.

While Smith wrote glowingly of Dorothy’s efforts at Rushmore, he did not mention her by name in the book — only as “Ziolkowski’s wife.” Researchers today won’t find Dorothy’s name in an anonymous Wikipedia article about Korczak, although the story makes clear he had two wives, the second of whom is named. Those kinds of omissions triggered Karlen’s thinking decades later about what sometimes happens to women in history, especially those from an era when no wife kept her original surname after marriage and often lost even her first name in newspaper accounts.

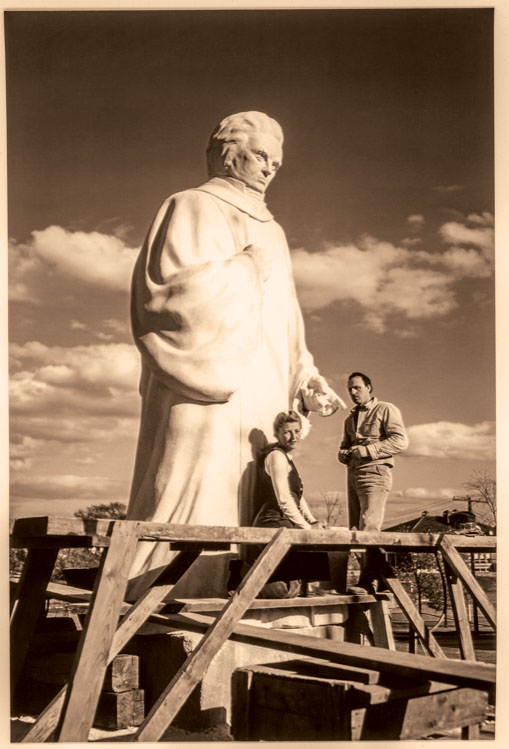

|

| Before coming to South Dakota, Ziolkowski carved likenesses of great leaders in history. He and Dorothy (pictured) gifted this statue of Noah Webster to the city of West Hartford, Connecticut. |

The year 1939 was significant for Dorothy and Korczak for reasons beyond Mount Rushmore. Korczak’s sculpture of Ignacy Jan Paderewski, a musician and Prime Minister of Poland, won first place in a New York World’s Fair competition. Korczak suddenly had the international arts community’s attention. But the summer didn’t end well. Lincoln Borglum, Gutzon’s son and a key part of the Rushmore project, got into a fistfight with Korczak. Lincoln and Korczak made up quickly and, Dorothy later wrote, the pair “are good friends.” But Gutzon decided the men couldn’t work together and dismissed Korczak. The Ziolkowskis left the Hills, not certain they would see them again, and certainly not guessing that the Paderewski sculpture would aid in their return.

Back East, in Connecticut, the two immersed themselves in the lifestyles of professional artists. “Korczak has had no vacation since I have known him,” Dorothy wrote to her Vassar friends. “One piece follows another without so much as a half-day’s interim. We don’t even take weekends off. While he works, I fiddle, for there seems to be a lot of programs to be given.”

Music of another style came into their lives when they formed a patriotic drum and fife corps that performed as New England soldiers and sailors deployed for World War II service. Dorothy’s widowed mother, Bertha Comstock, lived with the couple and crafted authentic-looking colonial costumes.

Korczak himself left for the Army in 1943 and hit the bloody beaches of Normandy in 1944. Dorothy noted that war changed Korczak — made the hardened man harder still. Korczak railed against “what he called the veneer of civilization,” Dorothy wrote, and “was much more intolerant of people in general.” Karlen thinks Dorothy’s ability, well-practiced, to stand as a buffer between Korczak and others was a key to his acceptance in the Black Hills in the late 1940s.

His post-war vision of himself and his family was life in South Dakota or Wyoming; he had accepted Lakota elder Henry Standing Bear’s invitation to create a mountain carving honoring American Indians. Standing Bear had been impressed by Korczak’s World’s Fair accomplishment, and his time in the Black Hills was a plus. The Bighorn Mountains of Wyoming were considered as a site, but South Dakota’s quality granite won out. Korczak selected Thunderhead Mountain near Custer and declared he would shape it into Crazy Horse astride a horse. The land and mineral rights were purchased in 1947. The same year, Korczak built an on-site house, and his family followed him West — Dorothy, Bertha and a little girl, Anne, adopted by the Ziolkowskis (Standing Bear called her Maiden of the Dawn). They were prepared to live in the Black Hills for as long as it would take to complete a mountain sculpture considerably bigger than Mount Rushmore.

Also arriving from Connecticut were half a dozen young women who would volunteer at Crazy Horse Memorial. The drums and fifes and costumes came West, too, for occasional Black Hills performances but, of course, the focus was the mountain. A dynamite blast in June 1948 was a baby step in removing rock to reach carving surfaces — a process that continues 73 years later.

But in 1949, for reasons known only to the couple, the Ziolkowski marriage ended. A year later, Korczak married Ruth Ross, one of the young volunteers from Connecticut. Certainly, there were those who guessed the recently arrived Dorothy would return to New England, but she didn’t. She, her mother and Anne set themselves up in a little house on Franklin Street in Rapid City. Dorothy went to work as a Rapid City Journal writer. She also joined other Rapid City musicians as violinist in a small orchestra and endured an unhappy second marriage.

Divorce from Korczak didn’t mean complete separation from Crazy Horse Memorial. Dorothy watched its development, believed in it fully, and sent encouraging letters to Korczak. Two years before her death she mailed a note to Korczak, saying: “I am always extremely interested and stimulated as I hear of the tremendous progress for which you alone are responsible, and which is your gift to a world in need.” Considering both the sculpture and sculptor to be of permanent historical importance, Dorothy penned a 300-page Korczak Ziolkowski biography (never published).

|

| The Ziolkowskis created a patriotic fife and drum corps while living in New England. The group came with them to South Dakota and is pictured with Henry Standing Bear, the man who convinced Ziolkowski to create a mountain carving in the Black Hills that honored all American Indians. |

When it was time for Anne to go to college, she looked west, not east, and selected the University of Arizona. Dorothy and Bertha moved to Tucson with her in 1960. Dorothy played with the Tucson Symphony and gave violin lessons. Bertha died in 1961 and Anne sadly followed in 1968 after developing leukemia. Dorothy passed away in 1978 and Korczak in 1982.

Twenty-seven years after Dorothy’s death, Karlen took that history course and was advised by her neighbor, who had known Dorothy slightly, that the sculptor’s wife for so many years might make a good subject for a paper. Karlen found Dorothy’s obituary and noticed a cousin in Tucson listed as a survivor.

“Nobody’s ever asked about her before,” said Lenci Loring of her accomplished cousin when Karlen phoned out of the blue. She invited Karlen to Thanksgiving in Tucson in 2005. The women spent the holiday going through boxes Dorothy left behind — content Loring later gifted to Karlen.

Back home, Karlen looked up people who had known Dorothy and Korczak as a couple, including journalist Bob Lee. Lee gave Karlen a 1948 Rapid City Journal feature he wrote that mentioned Dorothy’s own artistry and credited much of the Crazy Horse project’s “super-salesmanship” to Dorothy and Bertha, who “showed hospitality-wise westerners how to entertain in a grandiose style.” In 2018 Karlen flew to Vassar, where no one in the alumni office or library knew who Dorothy was. “But they were mesmerized by her story when we talked,” Karlen says. Vassar staff helped her search registrar files and the library to find transcripts and the newsy letters Dorothy wrote to her class of 1919 friends (“Dear 1919,” each begins). Karlen had enough information and perspectives to do occasional history talks in Rapid City and typically found audiences no less mesmerized than the Vassar staff. Now and then, however, she met people who told her she had to be mistaken about Dorothy’s very existence.

She fully understood the confusion. Two generations of South Dakotans knew the second Mrs. Ziolkowski — Ruth Ross Ziolkowski, mother to Korczak’s 10 children, and the iconic leader who stepped up after Korczak’s death to take Crazy Horse Memorial into the 21st century. Ruth can be credited for the decision to complete Crazy Horse’s face, handled millions of visitors from around the world, and fulfilled an educational mission.

“She did a wonderful job,” says Karlen, who met the second Mrs. Ziolkowski a few times before her 2014 death.

But Karlen is making it her task to remind South Dakotans of Dorothy, remarkable in her own right and certainly deserving of a recognized place in state history.

Editor’s Note: This story is revised from the November/December 2021 issue of South Dakota Magazine. To order a copy or to subscribe, call (800) 456-5117.

Comments

Thank you for a wonderful piece on Dorothy. Would love to talk with you. Thanks much, Paul Anger, 504-940-8683.