The Gift of South Dakota

Subscriptions to South Dakota Magazine make great gifts!

Subscribe today — 1 year (6 issues) is just $29!

Rails to Trails

|

| The Mickelson Trail follows the old Burlington Northern railroad line through the Black Hills. Photo by Chad Coppess/S.D. Tourism. |

For nearly a century, trains thundered along this north-south route. Passing over high railway trestles and through canyons, tunnels and the very heart of the Black Hills, they hauled passengers, freight and coal for Homestake Mine's boilers.

Then the trains stopped rolling. Three years later, in the summer of 1986, Guy Edwards, a former state legislator and then city councilman in Rapid City, got word that someone was tearing down old trestles along the route with a chainsaw. He was asked if someone could investigate the possibility of converting the Burlington Northern rail line to recreational use under the federal Rails to Trails Act.

|

| The 109-mile long trail includes more than 100 converted railroad bridges and four rock tunnels. Photo by Chad Coppess/S.D. Tourism. |

Edwards agreed to make a couple phone calls. Eventually he made about 5,000. He also spent a lot of his time and money. But a dozen years after the trail first was proposed, the final sections opened in the fall of 1998.

Known as the Mickelson Trail, the route once reserved for trains has become the domain of hikers, bicyclists and horseback riders. Its 109 miles are almost guaranteed to bring people face to face with deer, porcupines and wild turkeys. Spotting an elk or mountain goat isn't uncommon. Neither is spying towns since the trail connects to destinations that all Black Hills people know — Deadwood, Hill City, Custer — as well as lesser known places like Dumont, Mystic and Pringle.

Though it's not far from the more rugged Centennial Trail, which runs parallel to the Mickelson a few miles east, this trail is accessible to those unable to consider a strenuous hike. The grade never exceeds 4 percent. The surface is a smooth layer of crushed limestone. Promoters say perhaps short sections might be paved someday, allowing those in wheelchairs to experience a few miles under their own power.

Among the project's first supporters was George Mickelson, who had served in the legislature with Edwards. Mickelson came through with an early $50 contribution, and was elected governor just weeks after Edwards began organizing. The governor actively supported the effort during his administration, and after his 1993 death the trail was named in his honor.

Supporters, though, seemed in short supply early on. "Probably 95 percent of property owners along the trail were against us at first," Edwards says. “I could understand their position. After years of having trains go by their property, it appeared the corridor might quietly meld into the landscape when the line was abandoned."

In some cases, Burlington Northern was preparing to transfer land leases to adjacent property owners. In other cases, the railway never held the properties, but had easements as long as the line wasn't abandoned. Some property owners hoped for more privacy, and some had come up with development plans. When Edwards and fellow trail proponent Dick Lee appeared at meetings to discuss their project, they often faced 50 angry property owners. Especially vivid in Edwards' memory is an older man who visited him, almost teary, to say he'd worked on a development project for two years. But Burlington Northern wouldn't complete the property transfer, that man told Edwards, "because of a commitment they made to you."

|

| The trail surface is mostly crushed limestone and gravel and includes 15 trailheads between Edgemont and Deadwood. Photo by Chad Coppess/S.D. Tourism. |

The opponents, Edwards says, "put up a valiant, cohesive, well organized attempt to block the trail. They were good people. After five or six years, the opposition faded away."

It faded as Edwards and his supporters successfully argued that the line hadn't been abandoned. True, Burlington Northern was granted permission by the Interstate Commerce Commission to stop running trains, but trail supporters believed a rail line itself can't be considered abandoned unless the courts or Congress say so.

"When you look at federal laws related to railways, and easements for railways, you're looking at stacks of reading," Edwards says. "There aren't many fields where there's been more federal legislation."

All that reading paid off. The courts agreed the line wasn't abandoned. "Everyone thinks of Rails to Trails projects as primarily recreation," Edwards says. "But there's more to them than that. This is a means of keeping established public corridors in existence. A hundred years ago there was an economic need for the Black Hills corridor, and a hundred years in the future there may be another need for it that we can't even guess now. Meanwhile, we're using it for recreation."

|

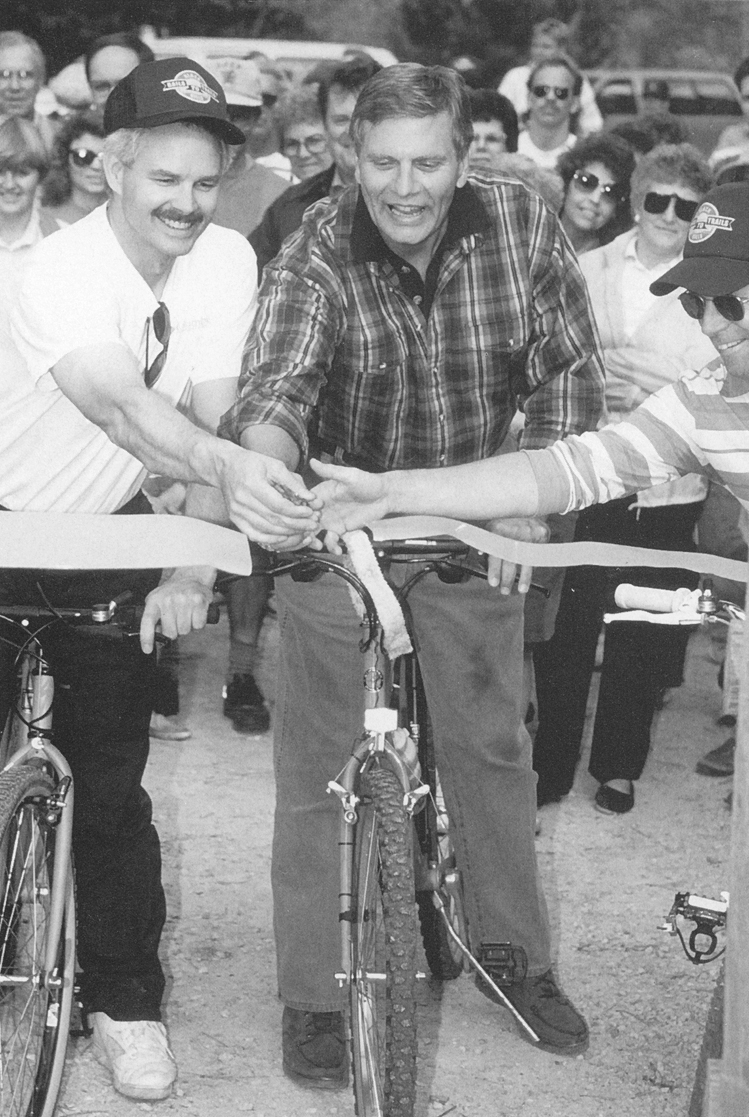

| The late Gov. George Mickelson was one of the trail's early supporters. |

He cites a rail corridor in Los Angeles that the city gave up when it appeared that trucking was driving freight trains to extinction. Later the city had to recreate the corridor at a tremendous cost.

Successfully arguing for the corridor, of course, was just the beginning of the work. Volunteers raised money and decked and railed old trestles. On board climbed an impressive coalition of federal, state, and private organizations: the National Guard supplied labor over the years, as would state Department of Corrections trustees. The U.S. Forest Service, state departments of Game, Fish and Parks and transportation, private building contractors and Burlington Northern all played key roles.

Burlington Northern, in fact, grew so supportive that it relinquished all its interest along the route — land, trestles, other wood that could have been salvaged — for just $20,000. The project expanded north to south: Deadwood to Hill City, Hill City to Custer, Custer to Edgemont. By the third phase, Custer to Edgemont, Burlington Northern had become so involved that it donated everything and became the first operating railroad to take a leadership role in invoking federal Rails to Trails status.

"The cooperation between individuals and agencies, all of whom have made this a high priority, has been amazing to see," says Harley Noem, West River regional manager for Game, Fish and Parks' Division of Parks and Recreation.

For three years prior to its opening, the trail was a big part of Noem's life. Prior to 1998, about half the trail was open. Trail completion meant a busy summer spent refurbishing trestles and two tunnels, in addition to surfacing and culvert work. Another massive job, taken on by a Department of Corrections crew, was building fences in compliance with adjacent landowners' needs. There are about 300 landowners, some of whom required barbed wire fences for cattle, or smooth wire for horses, or even wooden privacy fences for cabins.

Although developed for non-motorized travel, there are some winter exceptions, with stretches designated for snowmobilers. Trail towns have seen new businesses, such as bed and breakfasts and cycle shops, catering to trail users. But Black Hills residents and visitors alike see the most benefits. They see the countryside from a new perspective as they watch landscapes pass by slowly and quietly.

Editor’s Note: This story is revised from the September/October 1998 issue of South Dakota Magazine. To order a copy or to subscribe, call (800) 456-5117.

Comments