The Gift of South Dakota

Subscriptions to South Dakota Magazine make great gifts!

Subscribe today — 1 year (6 issues) is just $29!

Serenity in the Pocket

Feb 14, 2022

|

| The Pocket features Missouri River bottomlands and rough breaks rich with native grasses, ideal for grazing cattle. |

It was often a spontaneous decision motivated by the appearance of a fall storm front out of the northwest. In many ways we were like the migrating ducks and geese we were pursuing, driven half by the elements and half by instinct.

We would load into my friend Wes’ blue 1959 Chevy surrounded by the warmest clothes we could find at the Salvation Army, including vintage World War II wool storm coats and flight pants. Being 15, Wes had a learner’s permit that allowed him to drive from dawn to dark and no further than 50 miles from our hometown of Mitchell when not accompanied by an adult — limits that we constantly pushed, often leaving just as the sun set.

Our destination was his grandfather’s ranch in a little-known place called The Pocket, a farm and ranch neighborhood which lies just west of the Missouri River’s historic Big Bend. When we arrived in the dark and trudged through the front porch of the ranch house with our shotguns and clothes — past the saddles, spurs, branding irons and wire stretchers — often his grandfather Duffy wasn’t home. But when we woke before first light, he would always be seated at the kitchen table with a cup of hot instant coffee cradled in his hands, his eyes sparkling at the commotion of the gaggle of half-crazed boys around him.

A rodeo rider in the 1940s, Duffy always told us a story or two about life in The Pocket as he made us flapjacks and eggs before we headed out into the cold to wait for the geese and ducks to rise off the river and fly for the wheat and corn fields on the hills above.

Duffy had been known not only for his ability to land on his feet nearly every time he came to the end of his saddle bronc ride, but also for his Roman racing skills; apparently, he and his neighbor Howard Hansen would each stand on two horses and race around the arena.

Wes’ grandmother had been a member of the Crow Creek Tribe and one of the tribe’s first female council members. She had led tribal delegations to Washington, D.C., many years before. His great-great-grandmother, Many Tracks, first arrived in the area in 1863.

They, like other longtime families including the Big Eagles, the Hansens, the Halls, the St. Johns and the Howes, have forged a life tied to The Pocket, a place that still has one foot anchored in the past and another in the present. It is a tight-knit community of tribal members and nonmembers who have lived side by side for generations.

|

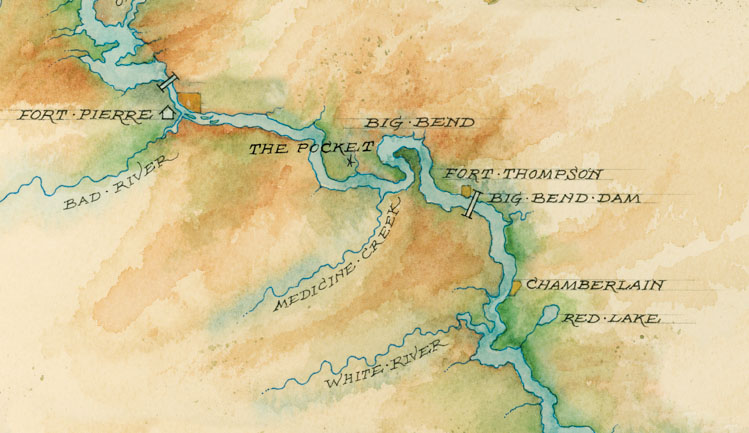

| The Pocket is tucked to the west of the Missouri River's Big Bend. Illustration by Mike Reagan. |

Most people drive by The Pocket without knowing it exists. Traveling east from Pierre along Highway 34, it is the expanse of land south of the road where the Missouri River disappears, only to re-emerge at Fort Thompson or De Grey. There is one main road, 316th Avenue, which horseshoes back as 319th Avenue. Within that horseshoe is a scattering of other farm paths known as Cut Across Road, Lonesome Road and Joe Creek Road. Like many interesting landscapes, The Pocket had a big beginning. A sheet of ice, half a mile thick in some places, paved its way through Canada and the northern U.S., stopping its advance roughly where the Missouri River exists today.

Tim Cowman, South Dakota’s state geologist, says that the glacier likely had “fingers” that extended off the main sheet of ice, reaching into what had been the bed of an ancient sea that today is comprised of a thick layer of hard Pierre shale.

“The river wants to run south, but it hits a protrusion of Pierre shale and bounces back northward until it hits another outcrop where it flows south again,” Cowman says. That pinball action created the bend in the river that 18th and early 19th century explorers often called the “Grand Detour.”

The glacier also gave the land within The Pocket its geological characteristics. Along its southern, eastern and western hillsides lie boulders and rocks — some as large as kitchen appliances — that the glacier pushed along its leading edge. Between Highway 34 and those leading edges is a rich layer of sandy and heavy loam, which, along with the Missouri River’s bottomlands, makes The Pocket highly productive agriculturally. In the 1880s, after bison herds had been decimated and Native Americans had been forced onto reservations, it was reportedly where the federal government grazed the cattle it provided to tribes as beef issues.

“It’s as good as any place to farm because the land is so good,” says Dick Hansen, who traces his roots in The Pocket to 1925 when his grandfather arrived at the request of the Crow Creek Tribe and broke 20 quarters of land for them in a year, an amazing feat considering the equipment that was available at the time. Farming there for more than 50 years, Hansen adds that the land has allowed him to plant, “a little bit of everything.”

It is also home to South Dakota’s only commercial mint farm, which was established in the 1980s on the river bottoms. Visitors to The Pocket can readily detect the herb in the air when it is growing or being harvested. The high-quality essential oil the mint farm produces has been sold to companies including Colgate Palmolive for use in toothpaste, and Mars Incorporated, which owns the Wrigley Company, producers of chewing gum. Along with mint, the farm also grows white and yellow popcorn for Jolly Time.

*****

Amidst and adjacent to these highly productive farm and livestock operations lie roughly 40 homes, including 20 that make up Big Bend Community — an enclave of tribal members that was established in the 1970s. The community’s anchors include St. Catherine’s Catholic Church and the adjacent community center, cemetery and pow wow grounds. The center is used for wakes, funerals, community gatherings and bingo.

|

| Sister Charles Palm plays the organ and tends to myriad duties at St. Catherine's Catholic Church. |

St. Catherine’s traces its origins back to the area’s first missionaries. The church was located on Missouri River bottomland nearby but was destroyed in the early 1960s after Big Bend Dam was built, and the tribe, like other tribes in South Dakota, lost thousands of fertile acres to rising waters. The current church building was moved from a location east of Stephan and includes some of the furnishings that were removed from the original church before the waters of Lake Sharpe consumed it. Also lost to the reservoir was Oscar Howe’s birthplace and childhood home where he lived until he went to the Santa Fe Indian School and studied art.

Community members are highly protective of The Pocket. That’s why they and others quickly opposed an idea to place a hazardous waste site there in the 1990s, in spite of the potential jobs it would have brought to a place with high unemployment. Today, a small billboard stands adjacent to the community, asking visitors and residents alike not to litter in order to protect “Grandmother Earth.”

Not surprisingly, The Pocket has always attracted people. Megan Ernst, the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers’ archaeologist for the Oahe Project, says prehistoric peoples lived there as far back as 5,000 B.C. They were followed by Woodland cultures, who cultivated local plants and inhabited small hamlets on the river bottoms, and then by ancestors of the Mandan, who fashioned larger villages where they grew maize, beans and squash and hunted bison.

The Mandan villages were located on higher ground above the river and sometimes included stockades and fortified ditches for protection from invaders. Today these sites are federally protected and lie mostly hidden beneath the blowing native prairie grasses.

Ernst says that access to water and highly productive agricultural lands was as important to the early dwellers as it is to today’s residents. “The Pocket was occupied back then for the same reasons it is occupied now,” she says.

*****

Unlike the time when the people of The Pocket needed to fortify their homes, today there is a sense of neighborliness and hospitality that some longtime residents say has always been there. “Everyone seems to be there for everyone else,” one resident said. “If someone needs help, everyone will come to help them. If there’s a fire, everyone shows up to put it out.”

|

| A campground at West Bend Recreation Area is a playground for travelers as well as people who live in The Pocket, such as Chris LaRoche, Lyndsey Parsons and their son Christopher. |

That sense of community extends to strangers as well. Once, in the early 1980s while I was traveling back to Pierre from Sioux Falls, I decided to stop and see my friend Wes, who by then was living on the ranch. He wasn’t home, and as I turned around in his driveway, my car slid into an icy ditch.

With the sun starting to sink, my car low on gas and the closest ranch several miles to the north, I had no choice but to begin to walk northward, into a howling wind on a February day when the air temperature had not risen above zero, and the windchill was somewhere in the area of 40 below. Wearing a suit, topcoat, dress shoes and no hat, I put my head down and did my best to stay focused on my destination in spite of the wind and the cold. Within 30 minutes, a pickup pulled up alongside me and the driver threw open the door and commanded that I get in.

He looked at me with a sense of concern and sympathy as I tried to warm up, my body shaking so severely that it was difficult to speak. When I finally told him what had happened and explained my connection to The Pocket, he took me back to the car and wouldn’t begin to help tow it out of the ditch until he was certain that I had warmed up and would be all right, even though I assured him I was fine. As I drove back up the gravel road to Highway 34, he stayed in my rearview mirror until I reached the highway.

*****

All South Dakotans and expats have a favorite location in their home state. Spend any time on their Facebook pages and you’ll see fond references to places like Spearfish Canyon, the Needles, Lake Oahe, Palisades State Park and others. For me, it will always be The Pocket.

|

| The author, Steve Kinsella, with his dog, Hutch, in The Pocket. |

It’s not so much the place itself — although its beauty and history rival any other location in South Dakota — but the sense of place. Any time I turn off Highway 34 and drive down that long gravel road, with each passing mile the world simultaneously becomes quieter and larger. I am overtaken by a feeling of peace and calmness as my field of vision becomes dominated by a sweeping landscape with views of the vast meandering river, its dark backdrop of Pierre shale anchoring it firmly in place.

I am not alone. When you ask people who live in The Pocket what they view as its most prominent feature, they often say it is the feeling of isolation and serenity they experience living there. That feeling led the postal service to name one of the ranch roads “Lonesome Place.”

Wes Parsons, who took over the ranch after his grandfather passed away in the 1980s, making him a fifth-generation landowner in The Pocket, says that sense of serenity evokes a feeling that never goes away, even for longtime residents.

“I’ve been asked why I don’t go on vacation,” he says. “When I stand on the bluffs and look around, I feel like I am on vacation all the time.”

Editor’s Note: This story is revised from the March/April 2021 issue of South Dakota Magazine. To order a copy or to subscribe, call (800) 456-5117.

Comments

Thank you

Send me newsletter.

Thank you