The Gift of South Dakota

Subscriptions to South Dakota Magazine make great gifts!

Subscribe today — 1 year (6 issues) is just $29!

Stopping the Green Glacier

|

| Cedar tree encroachment is becoming a problem in the Missouri River valley, choking out native species and reducing available forage for cattle. |

WE STOOD HIGH ATOP a ridge on Rich and Sara Grim’s ranch in Gregory County. The Missouri River below looked like a wide blue ribbon stretching from horizon to horizon. A gentle northwest breeze made the afternoon’s 91 degrees feel like 75. Cattle stood on a point along the river munching prairie grass, surrounded by the remnants of a thick grove of cedar trees.

“My nemesis,” Sara Grim said as she grabbed the soft branch of a cedar and began picking at its prickly needles.

She’s not the only rancher who’s grown to despise these hardy trees. Landowners along the Missouri River — especially in the four south central counties of Gregory, Charles Mix, Lyman and Brule — have slowly watched valuable pastureland succumb to eastern redcedars, which have fruitfully multiplied for decades, marching steadily north from Texas, through Oklahoma, Kansas and Nebraska, and now South Dakota. Farmers and ranchers in those southern states have long fought a losing battle against cedars, but many experts see South Dakota as the cedar frontier, the place where maybe the encroachment can finally be stopped. But to do so, landowners are having to get out of their comfort zones and reclaim acres through a force we’ve all been taught to fear — fire.

*****

HOMESTEADERS WHO POPULATED the central Plains in the 1800s were awestruck by the lack of trees. But in ravines and other protected areas stood eastern redcedars. A member of the juniper family, eastern redcedars are native to much of the eastern United States. In poor soil, they may never grow larger than a bush, but under ideal conditions they can reach 30 or 40 feet.

|

| Sara Grim has become a staunch supporter of prescribed burning to control cedar tree encroachment. |

They are drought tolerant and among the most important windbreak species on the Plains, qualities that eventually made cedars ideal for planting in shelterbelts. They can also reproduce prolifically, thanks to the birds and other small animals that ingest the tiny blue berries that sprout from a cedar’s branches. Studies have shown that the seeds pass through a bird’s digestive tract in 30 minutes, leading trees to sprout near their parent trees or along fence lines where birds might perch. Years of unchecked reproduction have led to cedar groves with canopies so thick that no vegetation can grow beneath. That decrease in forage worries cattle ranchers.

Sean Kelly, a South Dakota State University Extension Range Management Field Specialist based in Winner, says that every 1 percent increase in tree cover leads to a 1 percent loss in forage production. “It’s just a slow green glacier moving north,” Kelly says. “You see one or two out there in your pasture, and then five years later it’s 15 or 20. Before you know it, you’re trying to catch up and stay ahead of the curve. It’s hard for a rancher to stay in business very long if all they have is cedar forest and no grazing opportunities. And it can really start to snowball. If you’re not adjusting your stocking rates accordingly, it starts to spiral.”

Landowners began to act in 2011 when Doug Feltman asked the Natural Resources Conservation Service to survey his ranch south of Chamberlain to determine the impact of cedar trees. Using a series of five photographs of a north facing slope taken between 1981 and 2011, researchers determined that an area that once supported 10 cows could now barely support three. Feltman’s productive potential had decreased 70 percent due to cedar encroachment.

The NRCS then looked at neighboring Gregory County. Through aerial photography, maps, GPS and field work, researchers confirmed that 30 percent of the county was covered with a heavy to medium encroachment of cedar trees, judging by average trunk diameters.

A survey of 109 Gregory County landowners revealed that 80 percent were concerned about cedar encroachment. It also indicated that they were interested in learning more about prescribed burning. “Fire is the most economical way of controlling cedars, especially if you don’t have thick encroachment yet,” Kelly says. “When it was Native Americans and buffalo out here, natural wildfires kept invasive species like this at bay. Without that element of fire, they’ve been able to take over and keep spreading. That’s why we’re trying to reintroduce prescribed fire.”

|

| Members of the Mid-Missouri River Prescribed Burn Association create a fire line to help keep a burn under control. |

After a series of meetings that began in the spring of 2012, the Mid-Missouri River Prescribed Burn Association (MMRPBA) was officially incorporated in 2016. The organization is landowner-driven and governed by a seven-member board, all of whom own land within its four-county coverage area. Integrating guidelines from several government agencies and university experts, the association established a lengthy and detailed protocol that dictates precisely when and how they will initiate a burn.

“It’s a 15-page burn plan,” says Kelly, who also serves as vice president of the MMRPBA. “On a new burn unit, it’s easily a yearlong process.”

Every burn begins with an initial meeting between one or two board members and the landowner, who also must join the association and attend a prescribed burn on another member’s property before receiving burn services on his or her ranch. The group conducts four or five field visits throughout the year to determine the severity of cedar encroachment and identify other factors that will affect a potential burn: Where can they create fire breaks? Is any shearing needed? Are there hazards, such as power lines? Can safe escape routes be planned?

Once those questions are answered, work begins on the ignition plan. They determine how large the crew should be and what equipment will be needed. If possible, they try to incorporate one or two other landowners to utilize natural fire breaks. If a burn is planned all the way to the river, they work with the Department of Game, Fish and Parks and the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers.

Then it’s a matter of waiting for the right weather. Kelly says they generally follow the 80-20-20 rule, which calls for temperatures no hotter than 80 degrees, at least 20 percent humidity and wind under 20 miles an hour. Those parameters mean that March, April and May are prime burning months, followed by a few opportunities in the fall.

After years of preparing, perfect weather arrived in April of 2016. The association was ready for its first prescribed burn on the Grim ranch.

*****

SARA GRIM WAS A girl on horseback, helping her father move cattle through the river breaks of the family ranch. When they came to a grove of cedars, she got off and led the horse through. That’s when a cedar branch caught on the saddle horn and broke the latigo.

“Now that’s a memory,” she laughs. “I haven’t thought about that in years. I don’t remember how he dealt with that. We had bad cedar trees back then and the cattle would get in them. It was hard to get them out; we had to crawl or lead the horse through. My father was noticing a problem with cedar trees, but nobody knew what to do. We all hoped it would just go away on its own, but it didn’t.”

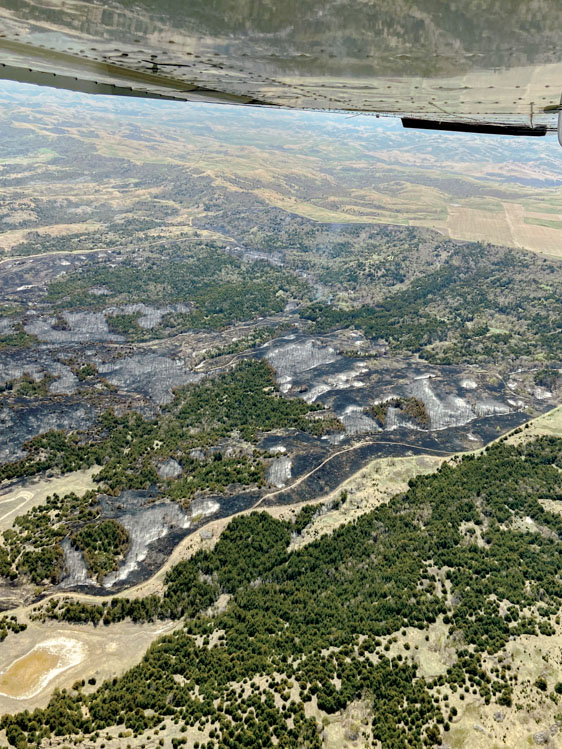

|

| An aerial photograph shows the darkened patches of the Grim ranch treated by prescribed burn in May of 2023. |

Grim’s grandfather, William Sutton, arrived on this patch of land in 1929. He was working for the Yeoman Mutual Life Insurance Company, which had ended up with the ranch after its original owners, the Jackson brothers (also owners of the vast Mulehead Ranch), went under. Sutton came from Iowa and within a couple years purchased the ranch from the insurance company. His ranch brand became the Y-S, for Yeoman and Sutton.

When Grim’s father Billie Sutton, a popular local politician, died in a farm accident in 1982, Grim and her brother came home to help their mother manage the ranch. Eventually they decided to split it in half. Grim and her husband work about 3,600 acres of rough river break country mostly dedicated to cattle that have slowly seen their grass get choked out by cedars.

About 10 years ago, the Grims began working with David Steffen, a retired NRCS employee living in Burke, on a Conservation Stewardship Program that focused on grassland management. The program included the idea of cedar control through burning.

Grim was still working in the county treasurer’s office, where she spent 27 years. “One day, Dave came into the courthouse and said, ‘Sara, what are we going to do about this green glacier?’” she recalls. He had brought an overlay showing the cedar encroachment in Gregory County. The Grims had helped develop the county landowner survey along with Steffen and were interested in prescribed burning, so they got involved.

They quickly learned that education is paramount. “I’ve talked to so many people who are just unaware. They look at those trees growing in the river hills, and they think it’s beautiful, but there’s nothing growing underneath. There’s no grass, no feed, and we’re losing ground.”

The association identified a section of the Grim ranch and formulated a burn plan. The Grims participated in a few controlled burns with local fire departments to prepare. “They were small experimental burns, and we were scared out of our minds,” she says. “I didn’t sleep for a week. It was very scary. For years if anyone saw a fire you put it out.”

But when they dropped the match on that April day, the association was in complete control. Flames roared and smoke billowed high into the sky. When it was all over, 340 acres of thick cedar forest had burned. Just as importantly, the blaze sparked confidence in the volunteers who were learning to manage such a destructive force. “You have to respect it, but you don’t have to fear it like you used to,” Grim says.

*****

PETE BAUMAN HAS been helping people get comfortable with fire for nearly 25 years. When he began, the focus was on using fire to help manage land enrolled in the Conservation Reserve Program. After he started working for SDSU in 2012, his efforts shifted to working with multiple organizations on creating classes where landowners could be introduced to fire.

|

| Cedars produce thousands of berries that are dispersed by birds and other animals. |

“There was just this general idea that South Dakotans had a fear of fire,” Bauman says. “But over the years, it became very clear that people didn’t have a fear of fire, they had a disconnect with fire. There was no innate fear. It was more like we forgot how to understand it.”

Bauman says the prairie evolved with three things: fire, grazing and climate. Indigenous people recognized the value of fires and ignited them to stimulate the regrowth of native grasses that would, in turn, attract the great bison herds. “It’s nature’s wonderful reset button,” Bauman says. “Healthy prairies really are not damaged by fire at any time of the year because native plants come back. Fire stimulates native plant growth, it recycles nutrients, it definitely stimulates total production, seed production and seed viability. Pollinator plants thrive post-fire, which then creates insect habitat. They utilize that smorgasbord of nectar that’s been created. When that all functions well, you’ve got the foraging animals. Those benefits just build up the line. It’s when we throw exotic species into the mix that makes the timing of fire so much more important.”

He says the goals of fire today are to control, reduce or eliminate exotic species like brome, bluegrass, Canada thistle and sweet clover. “Now we have to look at fire as a specific tool that has to do with timing, intensity and duration, very much like grazing. We have to apply fire not as a hammer but sometimes as a scalpel and understand what the objective is of each individual fire, and that’s different than it would have been 250 years ago.”

For the past three years, landowners have received hands-on training at fire schools that Bauman has supervised throughout eastern South Dakota. Bauman serves as the “burn boss” while attendees assume other leadership roles that a prescribed burn would require. “The coolest thing about prescribed fire is we’re in control,” he says. “We don’t ever have to drop the match. From the moment we start to the moment we stop, it’s about control, control, control, which makes the fire the tool. The tail doesn’t wag the dog. Our mantra is that we want you to be bored on your fire. If you’re bored, your fire is doing exactly what it should do. We don’t want the amped up, excited chaos associated with fire response. We want clear thinking, well planned, well executed, boring fires.”

However, Bauman says a boring fire isn’t enough for cedar infestations. “What those folks need to do to save their ranches requires a higher level of risk and coordination and fire intensity,” Bauman says. “The schools that we do help lay the foundation for those folks to build their skills, because it’s a different kind of fire. If you have a boring fire trying to kill cedar trees, you’re probably not going to kill many trees.”

*****

WE SPENT TWO HOURS traversing the vast Grim ranch by UTV. The gray skeletons of cedars burned in that first fire in 2016 are finally beginning to fall. Charred trunks and trees that sport splashes of brown amongst the green branches show evidence of the 530-acre burn they held on their West River pasture in May of 2023.

|

| Native plants such as snow-on-the-mountain have begun to re-emerge on patches of land treated by prescribed fire. |

“Oh, look at that switchgrass,” Sara Grim said, stopping the side-by-side so we could examine the new shoots already emerging, just three months after their most recent burn. Big bluestem waved in the breeze. The white flowers of snow-on-the-mountain contrasted against the blackened trunks of cedars that will eventually topple over.

That spring burn had been planned for seven years. In the meantime, the MMRPBA has kept busy with other fires. The group burned 688 acres in 2017, 271 acres in 2018 and 314 acres in 2020. Covid, drought and other hiccups put a hold on burning for a few years, but in 2023 they rebounded by burning roughly 6,000 acres. There are 10,940 acres on the books for prescribed burning in 2024.

Grim’s ranch is very near the heart of South Dakota’s cedar encroachment, but Kelly says the spread is evident, especially along the Little White River in Todd and Mellette counties and the Cheyenne and James River valleys. Its leading edge seems to be along Interstate 90, where groups are already experimenting with prescribed burns and working to form burn associations.

Sheldon Fletcher, with the Lower Brule Sioux Tribe’s Environmental Protection Office, has begun holding meetings and oversaw a 30-acre prescribed burn after traveling to watch the MMRPBA in action. Rod Voss, a Rangeland Management Specialist for NRCS based out of Mitchell, has helped with two prescribed burns along the James River. “We’re at a stage here where it would be fairly easy to stop if we can just get our people educated,” Voss says. “A lot of people are recognizing the production impacts, but it’s a hard thing to educate people that a tree can be a bad thing. Out here on the prairie, people like their trees, but a tree in the wrong place is simply a weed.”

That’s something the ranchers of south central South Dakota know all too well. Kelly hopes people in other parts of the state begin to see the benefits of fighting with fire. “It’s not an easy sell, especially in some of these areas where the encroachment is just starting and they’re not really sure if it’s a problem that’s worth spending any time on yet,” he says. “I can understand that, but if you don’t believe me come down and take a look at Gregory County, because this is what you might look like in 40 or 50 years. We’ve got a real opportunity to stop it.”

If they succeed, then South Dakota can be something that Texas, Oklahoma, Kansas and Nebraska could not: the cedar’s final frontier.

Editor’s Note: This story is revised from the November/December 2023 issue of South Dakota Magazine. To order a copy or to subscribe, call (800) 456-5117.

Comments