The Gift of South Dakota

Subscriptions to South Dakota Magazine make great gifts!

Subscribe today — 1 year (6 issues) is just $29!

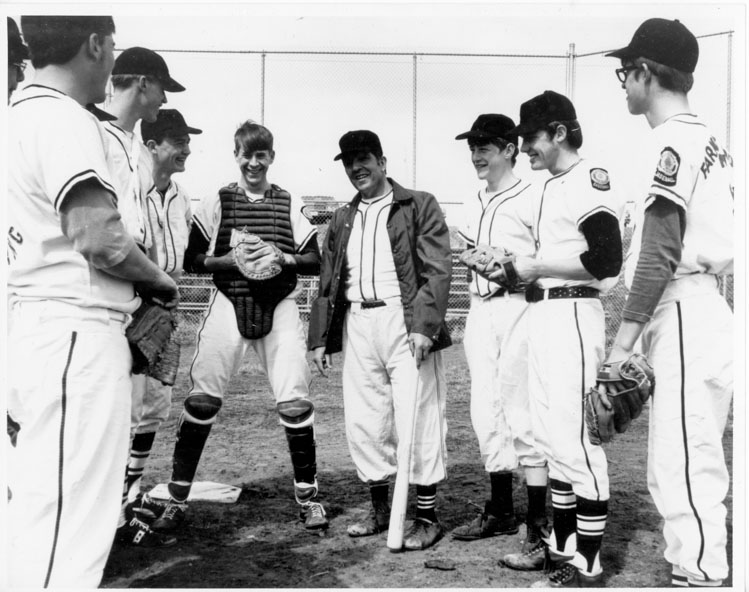

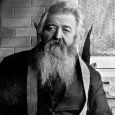

From Coach to Congress

|

| Jim Abdnor (center) coached Kennebec's Legion baseball team before embarking on a state and national political career. |

Jim Abdnor talked constantly, but no one in Kennebec had any inkling that their baseball coach would ever go to Washington. Two decades before he ran for the U.S. Senate in a race that drew national attention, Abdnor was simply a kind-hearted farmer who volunteered to coach the Legion team.

Nobody doubted his baseball smarts. He told Jim Cooney to try playing catcher, a position that didn’t appeal to the 9-year-old. But Abdnor, who would eventually gain a reputation as an astute spotter of green talent, recognized something in Cooney.

“I played baseball until I was 19 or 20,” says Cooney. “Always a catcher.”

Coach Abdnor chattered non-stop at the ballpark. And he talked at the coffee shop and the grain elevator and the school. He avoided gossip, however, and he never ranted when things went bad in a ballgame. In those years, the late 1950s and early 1960s, Abdnor almost always dressed like a working man in khaki pants and a green shirt. “It was like he had three sets of the same clothes,” Cooney recalls. The coach wore a mitt during practices but, in his late 30s, he was a bit too stocky to demonstrate proper fielding.

Abdnor eventually became a familiar figure in other South Dakota towns along old Highway 16 — Oacoma, Reliance, Presho, Murdo and Kadoka. He soon grew to understand and appreciate the culture of rural America. He inherently understood that the independent spirit and work ethic that defined the towns could also be found in many of the young people who grew up there.

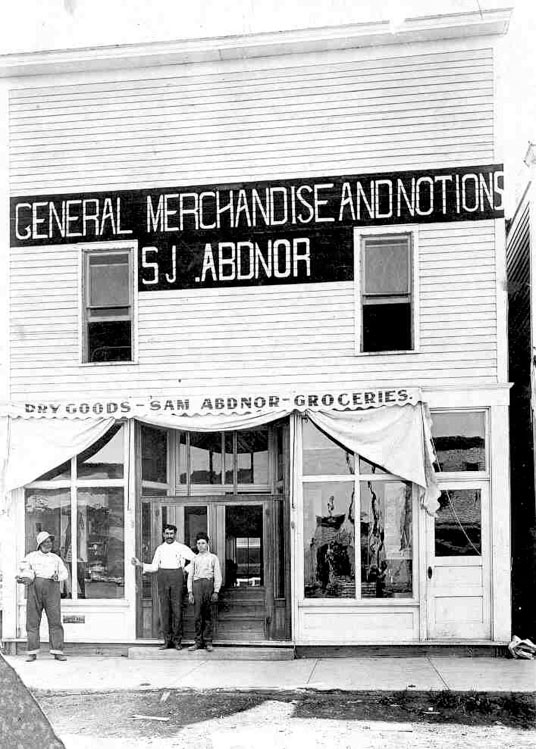

Abdnor was born in 1923, the son of Sam and Mary Abdnor, immigrants to South Dakota from Lebanon. The couple farmed and ran a Kennebec store. They weren’t the only Lebanese-Americans working hard for a living on the West River plains. Their good friends, Charlie and Lena Abourezk, owned the Abourezk Mercantile store at Mission. The two families got together regularly for Sunday dinners of traditional Lebanese food and to listen to records of music from the homeland.

|

| Abdnor's parents, Sam and Mary, were Lebanese immigrants who sold groceries in Lyman County. |

What’s more, the Abourezks also had a son named Jim, a few years younger than Abdnor. In time, the remarkable careers of the two Jims paralleled each other in uncanny fashion.

As was often true of children in immigrant families, Abdnor found sports as a way to absorb American values and cultural understandings. His Kennebec friends and neighbors were never too busy to support their teams. They also had political connections beyond what you might expect in a town of 400. Kennebec was home to U.S. Congressman William Williamson when Abdnor was a child, and M.Q. Sharpe — governor when Abdnor was a young man. The Lyman County courthouse sat on a hill on the south side of town, and the state capitol at Pierre was only an hour’s drive to the northwest.

Abdnor believed small communities had value, but he knew the economics of rural America were challenging, so he supported the Kennebec grain elevator and civic organizations that moved the town forward. As his political career grew, he made certain to use the Kennebec post office for his mailings — boosting local postal numbers. And it seemed almost as if he kept a roster in his hip pocket of the next generation of movers and shakers.

“If it were not for Jim Abdnor there is no way I could be doing what I’m doing today,” said current U.S. Senator John Thune in a eulogy for Abdnor in 2012. Abdnor first took note of Thune as an outstanding Murdo High School basketball player. While South Dakotans recall Abdnor as anything but flashy, Thune remembered “an understated charisma about him and an optimism that anything was possible.”

People responded to that throughout Abdnor’s life. He left Kennebec to earn a business degree at the University of Nebraska and served two years in the Army during World War II. Then he came home to help run the family businesses, teach history at the high school, and begin a 20-year stint coaching baseball. Soon another kind of work with young people put him on the road, in his spare time, building a network of Young Republican clubs. After World War II, both Republicans and Democrats recognized shifting South Dakota demographics and took action to strengthen their voter bases. In fact George McGovern — who will always be linked with Abdnor in South Dakota history — was crisscrossing the state to rebuild the Democratic party at about the same time Abdnor was connecting with young Republicans.

In 1956 Abdnor decided to seek a seat in the state legislature. Simultaneously, he knew he had to go to work on a very personal problem — a speech impediment that caused him to slur certain words. He feared that people meeting him for the first time in Pierre and elsewhere might think him drunk. Abdnor enlisted the help of a high school teacher, who understood speech problems, and he read books aloud, watching for problem words. His speech improved, although he never defeated the impediment completely. Eventually it became an endearing characteristic for many constituents and political contemporaries who understood that only a remarkable person could speak so poorly and still get elected to office.

He entered the state senate at Pierre in January of 1957, a time when the legislature was all male and not known for transparency. Committee meetings could be closed to the public at the whim of the chairman, and lots of deals were sealed in smoky rooms down the street from the capitol at the St. Charles Hotel. In both state and federal government, Abdnor always told friends in Kennebec, he disliked seeing colleagues vote against their principles in order to win votes later for another bill.

Abdnor in the legislature could be counted on to support public works (especially water projects), electric cooperatives in their territorial fights with public utilities and agricultural development.

Abdnor was reelected to the legislature five times and became president pro tem of the state senate. He ran successfully for lieutenant governor in 1968, following in the footsteps of A.C. Miller, another Kennebec politician and his personal mentor.

|

| As president pro tem of the South Dakota senate, Abdnor handled ceremonial duties while also delving into tough governmental issues. |

Then in 1970, his friend who shared his first name and Lebanese heritage, Jim Abourezk, was elected to the U.S. House of Representatives as a Democrat. He would represent the state’s old Second Congressional District (generally West River), and it could have been the two Jims running against one another that November. Abdnor sought the Republican nomination for the congressional seat but lost in the primary. Immediately, supporters urged him to try again in 1972, including Phil Hogen, an attorney who had just moved to Kennebec after completing law school at the University of South Dakota. Abdnor knew Hogen from a decade before, when he worked to get Hogen — then a Kadoka High School student — a position as a state senate messenger.

Hogen was among those who campaigned hard for Abdnor, and his story was typical of many volunteers and staff. They met Abdnor as young people and were committed to him for life. “He had a remarkable rapport with young people, and I’m not even sure why,” says Abdnor’s friend and Kennebec attorney, Herb Sundall. “I only know he could sit down and talk to them like no one else I ever saw. Jim never had children himself, never married, so maybe that had something to do with it.”

Abdnor and his young campaigners won the 1972 congressional race. Abourezk, after just 24 months, vacated the Second District seat and ran successfully for U.S. Senate. Abdnor reported to Washington as the only Republican member of South Dakota’s congressional delegation, consisting also of Democrats Abourezk, Sen. George McGovern and First District Congressman Frank Denholm.

He quickly needed to assemble a Washington staff. He soon had a Red Wing shoebox full of applications, many from Capitol Hill professionals who had been working for just-defeated members of Congress. Abdnor, though, decided he wanted his Kennebec friend and campaign organizer, Phil Hogen, to serve as his administrative assistant.

“Jim, I don’t want to do this,” Hogen remembers telling Abdnor when first asked. “But I changed my mind, and the two years I was in Washington were exciting. We’d been there 45 days when AIM occupied Wounded Knee, and we got to be on a first name basis with lots of people in the Bureau of Indian Affairs and the FBI.”

Hogen quickly came to understand he worked for a man who hated paperwork but loved people. “Lots of politicians go home and walk along the street, glad-handing and smiling at everyone they meet. But Jim did that with everyone he met, not just constituents who could vote for him, and he became very well known and liked in Washington.”

Abdnor watched the Watergate scandal engulf Washington from an unusual perspective in 1973 and 1974. Michigan Congressman Gerald Ford became a personal friend, and Abdnor saw Ford quickly elevated from Congress to vice president and, soon, to president of the United States. Three months after Ford replaced Richard Nixon in the White House, South Dakotans re-elected Abdnor, even though Republicans fared poorly nationwide due to the Watergate repercussions.

“For South Dakotans he was the personification of goodness in a rural state,” says Kay Jorgensen of Spearfish, who also grew up on the West River plains and served in the state legislature. “People saw his entire goal being to make individual lives better.”

|

| In Washington, Abdnor was as comfortable shaking hands with Queen Elizabeth as he was on the baseball diamond back in South Dakota. |

The state never knew a more accessible congressman, Jorgensen added. “He was someone you could always call. Often he answered the phone himself. And if you agreed or disagreed on an issue, it never affected the friendship.”

But even Abdnor’s most loyal friends wondered if the old coach was up to the challenge of running against George McGovern for U.S. Senate in 1980. McGovern had been the Democratic nominee for president eight years earlier, carried tremendous clout in Washington, and was a polished speaker and debater. How would Abdnor fare in a debate against George McGovern?

As it turned out, McGovern’s debating skills went for naught. The old baseball coach did the political version of an intentional walk: he declined all debates. Rather, he said, he would let his conservative record speak for itself. The national press took notice of the race, partly because of McGovern’s stature and partly because a Republican win would confirm that the party was making a strong comeback six years after Watergate.

Perhaps because it was so high profile, the 1980 Senate race split South Dakota communities and families, at least temporarily. “Although Jim’s mother, Mary, was my godmother, and his uncle Albert was my godfather,” wrote Jim Abourezk in his biography, “I never let that divert my attention from what I could do to campaign — unsuccessfully — for George McGovern.”

Abdnor won a landslide victory, claiming 58 percent of the vote, thanks in part to the Reagan revolution that swept across South Dakota and the national political landscape in 1980.

Though he declined debates during the campaign, Abdnor was not a silent senator. Three weeks after taking office, he spoke powerfully on behalf of a new group of individuals whose lives he hoped to make better. In the House of Representatives he had been an advocate for quality veterans’ health care. Now he discussed a particular category of veterans whose needs were just creeping into national consciousness: former Vietnam War prisoners whose problems, especially mental health issues, might not be evident for years. If symptoms did appear, Abdnor asserted, these veterans deserved prompt attention without waiting to prove their needs stemmed from the war. “We have waited for too long,” he said, “in addressing the unique and often severe problems former prisoners of war and their families face because of their internment and their services to their country.”

Abdnor especially appreciated his appointment to the Senate Appropriations Committee. He was sometimes asked how that worked for a fiscal conservative. “I didn’t spend any more money,” he later told the Sioux Falls Argus Leader. “I just tried to make sure South Dakota got its fair share. I don’t know of any other committee where I could have had as much influence.”

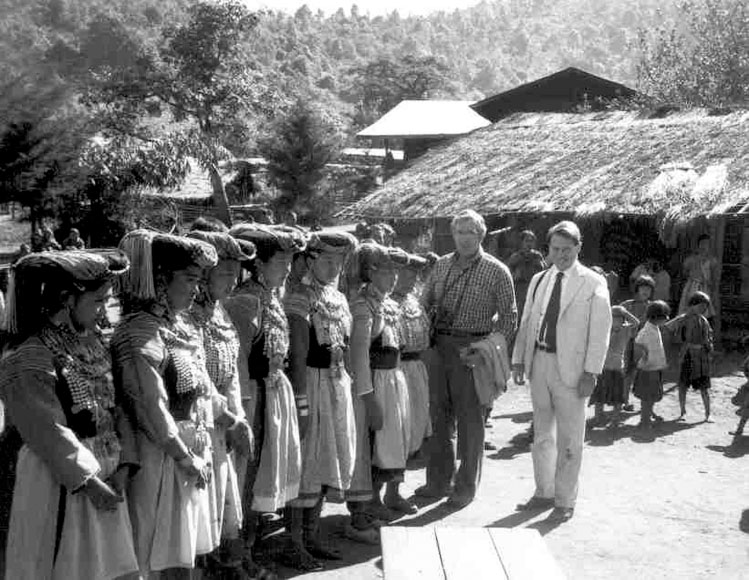

|

| Overseas tours exposed Abdnor to cultures far removed from life on the South Dakota plains. |

But he was unsuccessful in winning a second senate term in 1986. His support of the 1985 Farm Bill certainly cost him votes at a time when South Dakota farmers were suffering economically, losing their farms in some cases, and generally skeptical of federal agriculture policy. Gov. Bill Janklow had challenged Abdnor in the Republican primary. Abdnor prevailed over Janklow but the party was divided heading into the general election.

The old Abdnor-Abourezk connection re-asserted itself. Abdnor was defeated in 1986 by Tom Daschle, Abourezk’s former legislative director. Daschle would go on to serve three senate terms before being defeated by Abdnor’s protégé, John Thune, in 2004.

After leaving the Senate, Abdnor was appointed by President Reagan to lead the U.S. Small Business Administration. He served until after Reagan left the White House in 1989, then came home to South Dakota. He remained a sidelines force in the state Republican Party, and played golf. “Not very well, though,” Sundall says. “But he was always buying a new club that would make him the next Jack Nicklaus.”

He even formed a friendship with his 1980 opponent, George McGovern, who also spent many of his sunset years in South Dakota. “They didn’t agree politically but they respected one another’s honesty,” Sundall says. “Jim said when George told you he would do something, he did it.”

Abdnor also rekindled his love for youth baseball. He lived in Rapid City for several years and was a regular presence at games of the national powerhouse Post 22 American Legion team, even traveling to out-of-town games and out-of-state tournaments.

Baseball diamonds are where many South Dakotans had their last encounters with the senator from Kennebec. He would talk baseball, applaud the good plays and grab the hands of friends old and new.

Editor’s Note: This story is revised from the November/December 2018 issue of South Dakota Magazine. To order a copy or to subscribe, call (800) 456-5117.

Comments