The Gift of South Dakota

Subscriptions to South Dakota Magazine make great gifts!

Subscribe today — 1 year (6 issues) is just $29!

The Turtle on Snake Butte

May 2, 2018

|

| The stone turtle atop Snake Butte. Photo by John Mitchell. |

There are runic legends written in stone on hilltops across South Dakota — giant snakes, turtles, mythical beasts, human-like forms, sacred symbols. The meanings within these hieroglyphs are a mystery to most of us. Do they commemorate the deeds of flesh-and-blood beings of our corporeal world? Cosmic or supernatural events? If you could stand on a mountain and read the land like a topographical novel, would it read top-down, left-to-right?

Archaeologists try to unlock the secrets in the stone through methodical research. Others make like Moses drawing water from the rock of Horeb and listen to the voices in their heads.

In any case, you can't get a handle on Black Elk Speaks or Thus Spoke Zarathustra or Their Eyes Were Watching God without bothering to read them. How many of the stories once held in the collections of the vast land library have been lost to the elements, vandals or time? We'll never know, but plenty remain.

One such story-writ-in-stone is the Snake Butte turtle effigy near Pierre — one of hundreds of petroforms depicting animals, humans and mythical creatures that have been documented in South Dakota. Some have disappeared or been altered. Most — including the turtle effigy — are on private land and not officially protected.

|

| A marker directs visitors to Snake Butte, near Pierre. |

The Snake Butte turtle effigy site is accessible; though it’s on private land, the owners welcome considerate visitors. Take Highway 1804 about 4 miles north of Pierre. The turn off (which is a private driveway) is on the left just past Grey Goose Road. At the corner, you'll see a South Dakota State Historical Society sign with the heading, "Sioux Indian Mosaic." From there you can drive to the top of the driveway, park your vehicle (without blocking the driveway) and a sign to the left will direct you to a quarter-mile walk to the top of Snake Butte, overlooking the Missouri River just downstream from Oahe Dam. The effigy is inside a fenced enclosure.

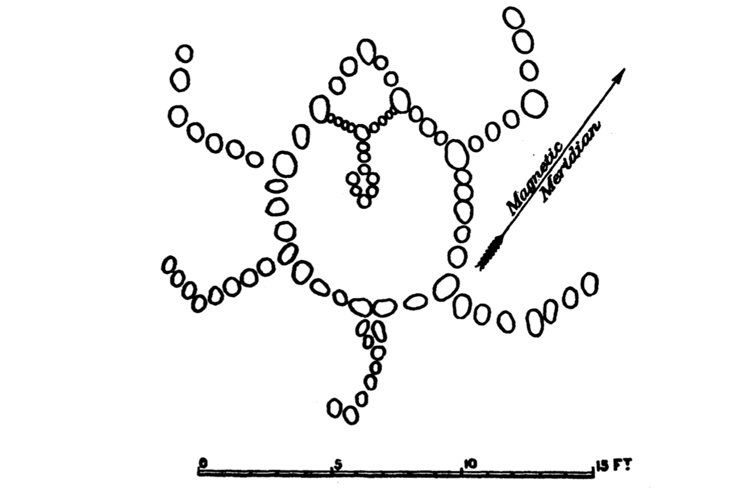

Archaeologist T.H. Lewis was the first to non-verbally document the site in 1889. He described the outline of a turtle (or possibly a beetle in his estimation), 15 feet long from nose to nail, and 8 feet wide, with four legs and a tail. "Running in a northerly direction along the edge of the bluff for from 500 to 800 yards there is a row of bowlders [sic], placed at irregular intervals. According to Indian tradition these bowlders mark the places where blood dripped from an Arikara chief, as he fled from the Dakotas, who had mortally wounded him."

Lewis also described, "many squares, circles, some parallelograms, and other figures" along the bluff.

In 1904, Thomas Riggs — a missionary who lived among the Dakota — related the story that he said a Dakota elder had told him about the stones "thirty years ago."

To paraphrase: An Arikara scout attempted to raid a Dakota camp on Snake Butte. He was discovered at dawn by a Dakota guard, who shot him with an arrow.

"The arrow," Riggs said, "had entered the hip in such a way as to render the leg useless and an incumbrance. He ran, or hopped rather, with marvelous swiftness, falling to the ground again and again; in agony and desperation he rose and continued his hopeless flight till overtaken and slain."

|

| This illustration appeared with an article written by archaeologist T.H. Lewis in 1889. |

"The victorious Dakota," said Riggs, "was filled with wonder and admiration, and that such astonishing spirit might have a fitting memorial, retracing his steps, he carefully placed a stone over each drop of blood and along the course where the wounded man had fallen he gathered small piles of stones, and larger piles to show the starting in the race and the end."

Recalling Riggs' retelling, state historian Doane Robinson wrote that the memorialist placed the turtle at the end of the line of stones, "to show the tribal lodge to which he belonged." The SDSHS sign near the site agrees with this interpretation of the turtle as a signifier for the Dakota band.

"As for which Lakota band is identified as the attackers, some say Itázipčho, some say Hokwojus," says Sebastian LeBeau, a BIA archaeologist and member of the Cheyenne River Sioux Tribe. Either way: "It's an authentic Lakota story."

One difference: in the version he knows, the Arikara warrior was defending his village, not the other way around. "He was running for his life to warn his people of an impending attack." There is plenty of archaeological evidence of Arikara village sites in the area around Oahe Dam, though there is no historical record of a particular battle between the Arikara and the Dakota/Lakota connected to this event. "Even in the oral tradition, there is no specification on whether or not a raid was carried out. It just stops with the creation of the turtle effigy."

"What's important is the commemoration of the great deed demonstrated by the dying Arikara."

Another difference in LeBeau's version of the story is what the turtle symbolizes. "As I was told, the significance of the turtle goes back to creating kinship. Through the brave act of the Arikara — the Lakota in respecting him and honoring him, created a kinship recognition. In some tellings, I've heard old people say they recognized this one as a relative because of his bravery. His concern was for his people and he struggled mightily to try and warn them."

"The central aspect of why one shares that story is to acknowledge not a great deed of the Lakota, but a great deed of an enemy. You measure your own self-worth or cultural worth as a warrior by who you fight with," says LeBeau, laughing. "The Arikaras were good fighters. They couldn't whip us, but we respected their ability in combat."

"What made me feel sad about [the effigy] when I first went to it, was that the actual stone path — elements of it are still there, but the whole path isn't."

While the turtle figure is protected by the enclosure, many of the stones the stories say symbolize the blood trail left by the brave warrior have disappeared, along with the geometric shapes and figures documented by T.H. Lewis.

The physical work itself isn't imposing — it's a big (by-turtle-standards) stone outline of a turtle on a hill — dwarfed by panoramic views of the river valley below. Conceptually, it stands alone. Memorials to fallen warriors, built by their enemies, are hard to find.

Michael Zimny is the social media engagement specialist for South Dakota Public Broadcasting in Vermillion. He blogs for SDPB and contributes arts columns to the South Dakota Magazine website.

Comments