The Gift of South Dakota

Subscriptions to South Dakota Magazine make great gifts!

Subscribe today — 1 year (6 issues) is just $29!

Tongues in Granite Cheeks

|

| Mount Rushmore is a point of pride, a vacation destination and a vehicle for the nation's humorists. |

South Dakota Magazine celebrated its 25th anniversary in 2010. For much of the previous year, we discussed how to celebrate such a significant milestone in the publishing world. Ideas for special stories in each of the year’s six issues took shape in editorial meetings and blossomed as we gathered the information and photos. But as we neared press time on the first issue of our anniversary year, one detail seemed to be missing: We needed an impactful way to kick everything off, something that combined the state culture that the magazine had explored for nearly a quarter century and the celebratory energy that we felt in our offices and hoped to convey to our readership.

Someone mentioned that Mount Rushmore, perhaps the most iconic and recognizable image associated with South Dakota, had never appeared on the magazine’s cover. What if we could find a way to make it look like those four, stoic granite heads were celebrating with us?

We located a beautiful photo by Chad Coppess, then a photographer with the South Dakota Department of Tourism and today this magazine’s photo editor. With his permission, we decided to have some fun. Or so we thought.

Our graphic designer skillfully added colorful, conical party hats to the top of each head, embellished with festive, silver tinsel where each hat met a rocky forehead. Directly below George Washington, we added a huge banner that appeared to be fixed to the mountain itself that read, “Happy Birthday SD Magazine,” and below that, the one-liner, “By George, we made the cover.”

We delighted in our mockup and sent the issue off to print around Thanksgiving. Our January/February issue is designed to arrive in mailboxes a few days before Christmas so that subscribers who receive it as a gift can enjoy a new issue during the holidays. Staffers received an unexpected gift, however, when readers saw the cover.

|

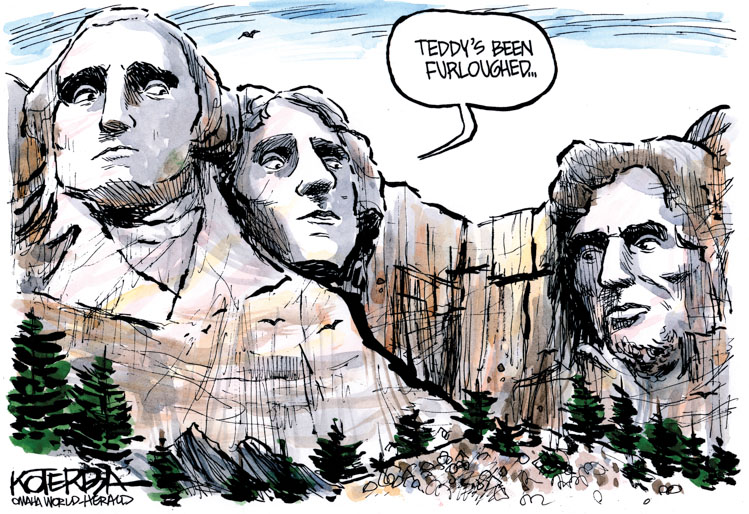

| Cartoonist Jeffrey Koterba drew this image of a Roosevelt-less Mount Rushmore during a government shutdown. He says the national memorial is a good vehicle for editorial cartoons because it is widely recognizable. |

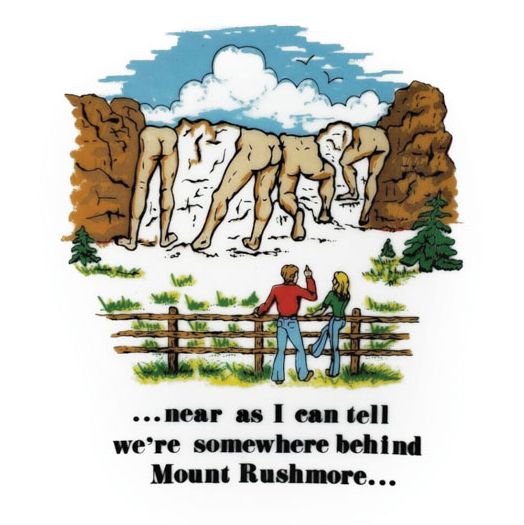

It was far from the magazine’s most controversial cover image. That goes to a friendly rattlesnake that slithered his way to the top of the list in the fall of 2002 and never again made an appearance in such a prominent position. (Honestly, we had no idea how many people have snake phobias!) But a few readers were upset that we had taken such liberties with the Shrine to Democracy. Some even thought we’d desecrated the national memorial, as if we’d truly traveled across the state and spraypainted birthday wishes onto the billion-year-old granite. We feared what might happen if those readers ever saw the iconic “backside of Mount Rushmore” postcard.

All jokes aside, when it came to Mount Rushmore we began to wonder if people thought all jokes should be set aside. Since the last piece of granite was chiseled away in 1941, the images of Washington, Jefferson, Roosevelt and Lincoln — locked into their stony gazes across the Black Hills — have slowly seeped into American popular culture. Their likenesses help sell cars, beer, toothpaste, shirts and hats. They show up on music albums, at theme parks, in Hollywood movies and newspapers — both in the comics section for pure entertainment and the opinion page as the vehicle for cartoonists who have something to say.

It seems, though, that Mount Rushmore has always had one foot in pop culture. Even when the memorial was still an idea inside state historian Doane Robinson’s mind, the motivation behind it was to draw tourists into the Black Hills. As roads began to improve in the 1920s, the Hills were already becoming a vacation destination for people longing for the cool mountain air and beautiful topography. But Robinson worried that it wasn’t enough. “Tourists soon get fed up on scenery unless it has something of special interest connected with it to make it impressive,” he said.

About the same time, he began reading reports of sculptor Gutzon Borglum’s massive undertaking east of Atlanta, Georgia, where he was attempting to carve Robert E. Lee, Stonewall Jackson, Jefferson Davis and other heroes of the Southern Confederacy into Stone Mountain. It served as inspiration for Robinson, who began dreaming of historical figures carved into the Needles.

In December of 1923 Robinson wrote to Lorado Taft, considered one of America’s pre-eminent sculptors, to gauge his interest in such a grand project. When Taft demurred, Robinson turned to Borglum in August 1924. Borglum’s relationship with the committee behind the Stone Mountain project had become strained and he was looking for a way out. Intrigued by Robinson’s proposal, he came to the Black Hills the fall of 1924 to see the lay of the land.

Borglum believed whole-heartedly in American exceptionalism, once saying that the records of the American people and their achievement should be “built into, cut into, the crust of this earth so that those records would have to melt or by wind be worn to dust before the record could, as Lincoln said, ‘perish from the earth.’” He also believed in big art. “Volume, great mass, has a greater emotional effect upon the observer than quality of form. Quality of form affects the mind; volume shocks the nerve or soul centers and is emotional in its effect.”

In the Black Hills, he discovered the perfect natural canvas to accomplish both of those aims. After abandoning the idea of full-bodied likenesses in the Needles, he began work at Mount Rushmore, a granite uplift that had been named years earlier for New York lawyer Charles Rushmore.

An air of patriotism and national pride surrounded the memorial from its start. President Calvin Coolidge attended a dedication ceremony during the summer he spent vacationing in the Black Hills in 1927. President Franklin Roosevelt visited in 1936 as Thomas Jefferson’s head was unveiled and was awed by the undertaking. “I had had no conception until about ten minutes ago not only of its magnitude but of its permanent beauty and of its permanent importance,” Roosevelt said in impromptu remarks.

|

| Among the most iconic and irreverent riffs on Mount Rushmore is the view from the "backside" of the mountain. It has appeared on postcards, T-shirts and commemorative plates. |

Work concluded on Mount Rushmore in October of 1941 under the leadership of Borglum’s son, Lincoln, who took over after his father’s death earlier that year. In 1933, President Roosevelt had signed an executive order placing the memorial under the jurisdiction of the National Park Service. That organization still serves as the guardian of Mount Rushmore, helping more than 2 million visitors each year learn about its history and trying to ensure that its image is not sullied.

Perhaps the earliest and most visible challenge came in 1958 when director Alfred Hitchcock planned to use Mount Rushmore in his thriller North by Northwest. The movie’s climactic scene featured Communist agents chasing stars Cary Grant and Eva Marie Saint across the faces.

The National Park Service was worried about such a depiction from the beginning. Officials signed an agreement with film studio Metro-Goldwin-Mayer in which producers promised that no violent scenes would be filmed “near the sculpture [or] on the talus slopes below the sculpture,” or on any simulation or mockup.

Hitchcock was upset with the situation and considered pulling the movie. But when he and film crews arrived to shoot scenes on Sept. 16, 1958, there were no problems. The Park Service even granted MGM permission to take several still images of the memorial before they headed back to California. That led to controversy when Hitchcock filmed the famous chase scene against a backdrop that was created using those images.

Park Service officials argued that Hitchcock had violated their agreement and that audiences would believe those scenes had been staged on the actual memorial. They demanded the removal of a credit line acknowledging the cooperation of the Interior Department and the National Park Service in filming at Mount Rushmore. The feds sought further help from South Dakota Sen. Karl Mundt, who in 1939 had successfully pulled from distribution a government-produced film called The Plow that Broke the Plains because of its inaccurate portrayal of the Midwest and his home state.

By then, however, little could be done. The credit line was removed, and the scene remained. In a 1991 article by Todd Epp for South Dakota History, Nicole Swigart, a seasonal interpreter at Mount Rushmore, wondered what Borglum would have thought. “It’s just my opinion,” she said, “but Borglum probably would’ve liked how the memorial was shown in North by Northwest. He liked publicity.”

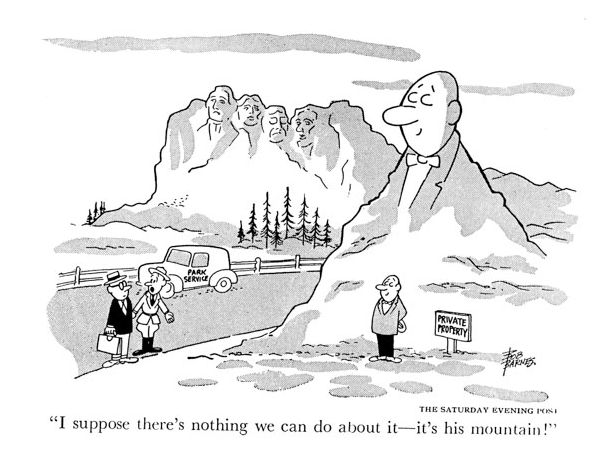

Cecelia Tichi, author of Embodiment of a Nation: Human Form in American Places, says the Hitchcock episode likely began the era of satirical depictions of Mount Rushmore, however two years earlier, the cover of the February 1957 issue of MAD Magazine featured a smiling Alfred E. Neuman sculpted at the foot of Rushmore.

Once the Rushmore image was out, it became nearly impossible to police its every use. In 1970, the band Deep Purple released an album called Deep Purple in Rock, which included sleeve art depicting the five band members carved into the mountain in place of the presidents. A Colgate-Palmolive television commercial from 1995 used Theodore Roosevelt to sell toothpaste. Computer graphics showed Roosevelt breaking out in a toothy grin after his teeth had been power washed. That image transitioned to a man using Colgate toothpaste.

|

| Marty Two Bulls rarely draws Mount Rushmore, but he turned to the four faces to help illustrate opposition to the Keystone XL pipeline in 2016. Two Bulls grew up on the Pine Ridge Reservation and was a finalist for the Pulitzer Prize in editorial cartooning in 2021. |

An episode of the Fox animated series Family Guy parodied the North by Northwest chase scene in 2005. A huge Lego Mount Rushmore stands at California’s Legoland, complete with a crew cleaning Washington’s left ear with a giant Lego Q-tip. One online retailer offers a Mount Rushmore dartboard (you’ll hit the bull’s-eye by firing a dart at the left corner of Jefferson’s mouth). Small replicas are offered on several websites that feature other figures in place of the presidents — stars of classic and modern horror films, Disney characters and the Golden Girls.

Closer to home, a logo of Custer’s Mt. Rushmore Brewing Company and Pounding Fathers restaurant features the four faces, plus an arm added to Washington and Lincoln. Both men are gripping a pint.

The image of Mount Rushmore appears today in ways that Robinson and Borglum likely never imagined. So how much is too much? Is there a line? What makes people care?

“People are fickle,” says James Popovich, who served as Mount Rushmore’s chief of interpretation for 20 years before retiring in 2004. “Some will say it’s just in fun and others will say it degrades the memorial. There are thoughts on both sides, and you have to respect them.”

In his two decades at the memorial, Popovich saw incredible demand for Mount Rushmore imagery in advertising. That usage sometimes rubbed people the wrong way. “People want to use any kind of logo from a national park, or Mount Rushmore especially, because it’s such an iconic symbol of America,” he says. “They want to use them in advertising or in any way to attract people to their business. So people do feel really particular about making sure the memorial is protected and safe for everybody to see and to see it the way they think it should be.

“The park service people, I think they feel a little unhappy about it when they first see it, but even me, as I saw it over time, I began to recognize why people do it. It sells literature, T-shirts, cups and hats, and that’s what they’re in business for, too.”

The memorial has also become a favorite for cartoonists, whose riffs on Rushmore have appeared in newspapers and magazines for decades. Jeffrey Koterba is a nationally syndicated cartoonist. He grew up in Omaha and spent 31 years with the Omaha World-Herald, where he drew more than 12,000 cartoons. Today his work is distributed through Cagle Cartoons and appears in 700 to 800 newspapers worldwide. He says Mount Rushmore is a natural fit for cartoonists because it’s recognizable — a trait that he thinks is becoming rarer. “When I was first starting out in cartooning, you could reference a film or a book, and even if you hadn’t seen the film or read the book, you at least had some understating of what it was, and I could use that for a cartoon,” Koterba says. “But today, there aren’t that many things that are so quickly identifiable in American culture. To me, Mount Rushmore stands pretty much at the top of the list. Everyone knows what that is.”

A notable Rushmore cartoon of his was born out of the federal government shutdown in late 2018 and early 2019. Washington, Jefferson and Lincoln gaze at a blank space on the mountain where Roosevelt should be. “Teddy’s been furloughed,” Jefferson quips.

|

| As Mount Rushmore gradually solidified its place in modern popular culture, cartoons became much more widespread, appearing in national publications like The Saturday Evening Post. |

Koterba put a lot of thought into that cartoon — the recognizable image, the implications that a government shutdown could have on the memorial itself and his audience’s potential reaction. “It’s my job to look for an image, or something using very few words, to get the idea across in a fast way,” he says. “They say the average reader spends 7 seconds with a cartoon. I thought, ‘What is something we all recognize as a symbol of our country and is somewhat related to the government?’ And I thought it was funny. I am going for a joke, not just for the sake of the joke, but ultimately to make a point.”

And then there’s the art itself. “I chose Teddy because visually, where it landed seemed like a good place. You wouldn’t want to do either president on the end. It made it more glaring. And it’s my job to take the reader by surprise. You don’t expect to see that image missing one of the faces.”

Koterba’s cartoons have featured the Statue of Liberty, George Washington’s famous crossing of the Delaware River during the Revolutionary War and the Mona Lisa. Locally, he’s drawn several cartoons featuring The Sower, a prominent sculpture atop the state capitol in Lincoln. He doesn’t recall any negative feedback in using those as vehicles. That could be because his audience is worldwide. Local readers may be more inclined to object with what they see as an unfit portrayal of a memorial or point of pride in their own backyard.

“When I’m coming up with a cartoon idea, it’s coming from a good place with good intent, based in journalism, based in fact,” Koterba says. “Yes, it’s my opinion, but I’m basing my opinion on fact as I see it. If I’m setting out to make a point that I believe is a valid point, I have to make people think. How can I portray that in a cartoon and get you to think about something in a different way? I’m not trying to change anyone’s mind, just add my voice to the conversation.

“I have respect for monuments and paintings and symbols and the American flag. It’s never my intent to rile people up,” he says. “But if it’s a symbol that people recognize and I can use it as a vehicle to make a point, then I think it’s fair game. I don’t see it as such a sacred thing that it is above being able to be used for satire or cartoons.”

Maybe it’s true that Borglum — ever the publicity seeker — would delight in the universal access to his grand creation that the 21st century allows, and that millions of people around the world can see it in periodicals, on television, in movies and on the internet, portrayed both solemnly and respectfully and occasionally with tongue planted firmly in cheek. He might even think it’s worth celebrating.

Where are the party hats?

Editor’s Note: This story is revised from the January/February 2023 issue of South Dakota Magazine. To order a copy or to subscribe, call (800) 456-5117.

Comments