The Gift of South Dakota

Subscriptions to South Dakota Magazine make great gifts!

Subscribe today — 1 year (6 issues) is just $29!

Doane’s Favorite Places

|

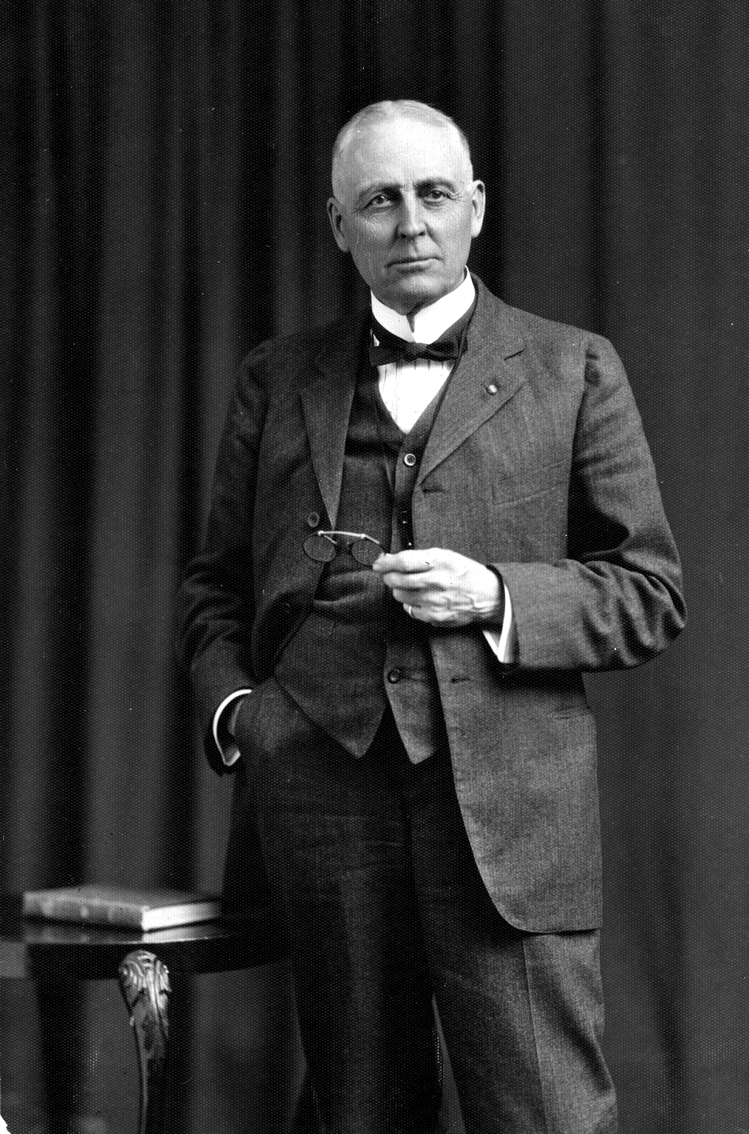

| Doane Robinson began his career in law, but eventually he became a poet, writer, publisher and state historian. |

It’s an eight-minute walk in Pierre from Doane Robinson’s former home on Wynoka Street to the state capitol building, where he once had an office. Eight minutes, that is, if you walk with a sense of purpose.

And it is impossible to think of Doane Robinson ever moving without a sense of purpose. In the early days of South Dakota statehood he was South Dakota’s idea man, and he ranks among our most prolific writers. Usually men of letters leave behind books, and men with big ideas leave thinking that spurs others into action over time. Certainly Robinson’s legacy includes books and inspiration, but he also left South Dakota beautiful buildings at Gary, Pierre and Hisega, as well as a solid foundation for a department of state government. Oh yes ... there’s also that sculpture of four presidential heads blasted from mountain granite near Keystone.

Robinson’s grandson, Will Doane Robinson, a retired teacher in Rapid City, remembers long walks along Wynoka and beyond with his grandfather in the 1930s. “A very, very nice man,” he describes him, and other neighborhood children concurred, often tagging along on walks. At the time they had no real idea of who their older friend was. Professionally Doane Robinson was a homesteader, teacher, lawyer, poet, editor and South Dakota’s first state historian. In his personal life he was a devoted family man who was widowed young. In his spare time he sometimes tinkered trying to invent a perpetual motion machine.

Born into a farm family near Sparta, Wisconsin in 1856, he was christened Jonah LeRoy Robinson. Two childhood incidents impacted the rest of his life. First, younger sister Sadie couldn’t pronounce Jonah and called him Donah, later shortened to Doane. He answered to the name the rest of his life. The second event, says great-granddaughter Vicki McLain, was much darker. Typhoid fever hit his family. No one died, but the family struggled for years to pay medical bills, keeping them in poverty for most of Doane’s childhood. Forever after, Robinson believed debt had to be avoided if at all possible.

He possessed an amazing memory, claiming he could recall incidents that happened before age 2, and maybe even before age 1. Robinson seemed strangely attuned to history-in-the-making. He remembered his parents discussing news that Abraham Lincoln had been elected president the month after Robinson turned 4. His parents were Democrats and he recalled they were unimpressed with the Republican Lincoln. Later he heard talk of distant fighting as the Civil War played out, and Robinson remembered news of Lincoln’s assassination — his mother worried Democrats would take the blame. Much later Robinson decided “in some ways the truth about Lincoln had been withheld from me,” and he committed himself to reading political theory. He became a Republican but, he wrote, “will give my support to another party any minute I am convinced that the sum of happiness will be enhanced by it.”

During his teens he worked hard on the farm, was able to run the place on his own in the event of family emergencies, and he worked equally hard in school where he honed his love of words. In his early 20s he taught school, homesteaded near his brother’s place in Minnesota, and began studying law at the University of Wisconsin. All the while he fretted about Jennie Austin, a Wisconsin girl he greatly admired and found beautiful, but who was a teenager too young for him.

|

| Robinson fell in love with a spot he saw while traveling on the Crouch railroad line. He named it Hisega, and soon build a lodge there featuring a wraparound porch. Photo by Paul Horsted |

Of course, Jennie matured. She became a teacher herself. The two decided their affection was mutual in 1883, the same year Robinson got serious about finding legal work in western Minnesota or across the border in Dakota Territory. He hadn’t earned a law degree but had learned enough to feel confident he could offer quality legal services — not an unusual course of action at the time. He considered setting himself up in Ortonville, Minnesota, but didn’t like the town. Then he visited Watertown “and made up my mind I had found the place I was looking for.” He opened a Watertown law office in September of 1883.

Months later he bought one-third interest in the Watertown Daily Courier. “The law is a jealous mistress and must come before anything else in your life,” Robinson would one day counsel his son Will, an attorney. By buying into the newspaper and, in fact, becoming its editor, Robinson demonstrated an unwillingness to focus on the law alone. The result, he decided later, was failing to be “much shucks” as a lawyer.

In December of 1884, Watertown’s young lawyer and editor rode the rails to Wisconsin to marry Jennie. Then the couple came home to Dakota Territory. Son Harry was born in 1888, and Will came along in 1893. In those years Robinson learned he could supplement his family’s income nicely by selling poetry to magazines across the country. He actually attracted a national following. The Boston Herald noted that “perhaps no one of the younger poets of America has so quickly established himself in the hearts of the common people.” Robinson came to know South Dakota in part because of requests to travel from town to town and recite his verse. His dialect poetry, recreating the speech patterns of the state’s immigrants, often for humorous effect, was well received. He also toured other Midwestern states. Even after he became state historian, Robinson remained a poet, and found he could sometimes combine verse and historical interpretation. An example is this poem about W.H.H. Beadle, Civil War veteran and pioneering educator who championed South Dakota School and Public Lands for generating public education funds:

Man of vision! Man of mission,

Patriot, soldier, scholar, seer.

Man of action! Man of purpose! Duty led

in thy career.

Forward looking; self forgetting; unwaged

drudge for learning’s gain;

South Dakota reaps the harvest planted by

thy care and pain.

In 1894 he moved his young family to Gary, a railroad town in Deuel County, close to the Minnesota border. He bought the Gary Interstate newspaper. “Getting out an edition of the eight page newspaper was frequently a family affair,” son Will recalled in an excellent little biography of his father. “The press was an old Washington hand press.” Jennie positioned the newsprint in the press and Doane swung a big lever to apply pressure and make the imprint. At age 6 Harry removed the finished newspapers from the press and stacked them.

|

| After the town of Gary lost its status as the seat of Deuel County, Robinson urged the state to locate the School for the Blind there. Today the campus is the Buffalo Ridge Resort and Business Center. |

The year after the Robinsons moved to town, Gary lost county seat status to Clear Lake. But the new newspaper publisher had an idea: Why not lobby the state to build a School for the Blind on the former courthouse grounds? Robinson did some research and determined it cost South Dakota $2,000 per student, every year, to send children with visual impairments to out-of-state institutions, in the era when it was assumed students with disabilities learned best in segregated environments. Robinson’s idea won statewide support and ground was broken in 1899. Students arrived in 1900. Vicki McLain thinks perhaps there was more to her great-grandfather’s passion for the school than commerce for Gary. “When he was studying law in Wisconsin,” she says, “he temporarily lost sight, apparently because of severe eye strain. He recovered but never took eyesight for granted.”

Over the next several years the school evolved into a pretty campus a couple blocks north of Gary’s business district. Services moved to Aberdeen in 1961 and the campus fell into disrepair, but more than 40 years later Joe Kolbach completed a beautiful restoration, creating Buffalo Ridge Resort.

Even as he was publishing the Interstate and advocating for the school, Robinson nursed a pet project, one he believed in so much that he was willing to sometimes serve as an “unpaid drudge,” to borrow a phrase from his Beadle poem. The idea was a magazine, the Monthly South Dakotan, that would heavily emphasize the young state’s history. Issues were produced over a period of several years and wherever Robinson moved, the magazine went with him. The Robinsons moved to Yankton where he bought controlling interest in a morning paper, The Gazette, and then it was on to Sioux Falls where Robinson hoped to find more ad revenue for the Monthly South Dakotan. Next the family made Aberdeen its home, and Robinson published the Brown County Review.

“He had a thousand irons in the fire,” Will wrote. As for the Monthly South Dakotan, he added, it claimed a loyal readership willing to pay for subscriptions, but ad revenue constantly fell short. The publication folded in 1904, and by that time Robinson’s life had changed drastically. In 1901 he was selected Secretary of the new South Dakota State Historical Society, a branch of state government. Now he had the opportunity to publish articles of the sort he prepared for the Monthly South Dakotan, but at state expense. After a few years in the position his income would allow for a very comfortable lifestyle. It should have been a happy time, but in 1902 Jennie died of acute bronchitis. Who else but Robinson, with his head for historical dates, would note that Jennie died 19 years to the day after she and Doane decided they were in love?

|

| Robinson advocated for the stately Soldiers and Sailors Memorial in Pierre after World War I. It once housed the state's history museum. Photo by Chad Coppess/S.D. Tourism |

“Oh, my dear boys,” Robinson later wrote his sons, “I can never tell you how dearly I loved your Mama, not only those nineteen years, but long before, and every moment since.” He was 45 and never remarried.

Sadie, the sister who gave him his name, moved in to help run the household. The family relocated to Pierre and Robinson arranged for construction of the home on Wynoka Street. Future governor and U.S. senator Peter Norbeck would be a neighbor on Wynoka, and became Robinson’s good friend and ally.

Robinson perhaps occasionally lost himself in work as he grieved Jennie. He helped plan the state capitol building and wrote 1905’s Brief History of South Dakota, more commonly called “the little red history book,” which for decades was the standard volume schools used to teach about South Dakota’s past. Most important, though, Robinson got the State Historical Society off to a strong start, publishing the first volumes of South Dakota Historical Collections, the biennial series of papers that most every South Dakota historian has referenced.

“His was the foundation we’ve built on ever since,” says Jay Vogt, current State Historical Society director. “In his time, he was much more hands-on than we’re able to be, doing most of the research and writing himself.”

Indeed, when something big developed, such as the discovery of the Verendrye plate that proved French trappers passed through the state in 1743, Robinson jumped into action and researched, wrote and edited until he had 300 pages for Historical Collections. He also gathered South Dakota newspapers and indexed them, along with government documents, and he took special interest in seeking out American Indian historical perspectives. He considered it a great honor, before his state historian years, to have interviewed Hunkpapa leader Gall, one of the victors at the Battle of Little Big Horn.

While no one ever questioned Robinson’s work ethic, he has sometimes been criticized for not being an academically trained historian.

“But you have to put that criticism in context,” says Vogt. “At that time, in all states, history organizations were kind of amateur clubs, made up of people who had interest and maybe connections to historical sources. Doane Robinson brought a wide range of professional experiences to his work, and he possessed great curiosity.”

For many years his office was on the capitol building’s ground floor, along with a little museum. When the legislature was in session, lawmakers knew the state’s best writer was close at hand if they struggled with a bill’s wording.

After railroad tracks spanned the Missouri River and were extended west to Rapid City in 1907, Robinson had easy access to the Black Hills for the first time. The region offered intriguing history, and it was a perfect place to relax. In 1908 Robinson arranged a camping adventure for 17 friends, relatives and Pierre colleagues. The party stepped off the Crouch Line train in a beautiful canyon west of Rapid City and pitched tents. Robinson loved making up words and announced he would call the spot Hisega, a name derived from the initials of six women in the group: Helen, Ida, Sadie, Ethel, Grace and Ada. Everyone loved the place, talked it up back in Pierre, and Robinson devised a time-share scheme. If enough people contributed $100, he would build a mountain lodge for them at Hisega. The big structure with wrap-around porches awaited visitors the next summer, and it still greets guests today.

A building of an entirely different style that stands as a Doane Robinson legacy is the Soldiers and Sailors Memorial, down the front steps and immediately across the street from the state capitol. Robinson pushed for the building after World War I, and it took more than a decade to raise funds and get the stately memorial finished. In addition to honoring South Dakotans who served and died in military service, the building housed the state’s history museum for many years and was usually referred to as the Robinson Museum.

|

| Robinson dreamed of carving into Black Hills mountains. Newspapermen called the idea ridiculous, but Robinson partnered with Gutzon Borglum and history was made. Photo by S.D. Tourism |

Of course, when it comes to tangible legacies, nothing tops Mount Rushmore Memorial. “My grandfather thought the Black Hills were beautiful, but that not enough people would visit just because of that,” says Will D. Robinson. “There had to be some other reason. I can show you the spot on the Needles Highway where his Model T Ford touring sedan got hot one day, and he sent my dad to bring water from a spring. When my dad got back to the car, my grandfather was looking at the Needles, thinking how they could be carved by a sculptor.”

That was 1923. Robinson talked to people who might help, especially Senator Norbeck, and sometimes took heat from South Dakota newspaper editors who considered the scheme ridiculous. But in short order internationally renowned sculptor Gutzon Borglum was on board and in 1927, as Robinson looked on, President Calvin Coolidge was present for a ceremony launching the project. Only the location wasn’t the Needles but nearby Mount Rushmore because, Robinson’s grandson understood, the Needles spires contained too much feldspar and Borglum didn’t want to alter that stunning piece of God’s handiwork.

Borglum also didn’t want to carve figures related to the American West, as Robinson proposed, but instead presidents. In Borglum, Robinson met a man whose vast vision matched his own. In another way, though, the men were polar opposites. Borglum liked to move ahead without much thought about costs, while Robinson insisted on budgetary constraint. As an executive of the original association formed to oversee Mount Rushmore’s creation, it fell to Robinson to confront the sculptor at times about spending. He was happy to pretty much leave the project in 1929, content in knowing his role as instigator had been successful. Robinson was back at the mountain on July 4, 1930, as a speaker when the Washington head was dedicated. He was 73 and had retired as State Historical Society Secretary six years earlier.

In the 1930s Robinson had more time for his walks and young friends on Wynoka Street, and he kept writing. Unlike Borglum and Norbeck, he lived long enough to see Mount Rushmore in its final form. He also saw his son Will become head of the State Historical Society in 1946. Doane Robinson lived a few weeks past his 90th birthday and his grandson recalls his mind and memories were as sharp as ever toward the end. He had witnessed America’s evolution from Abraham Lincoln to the atomic age. No one observed South Dakota’s first half century more intently.

Editor’s Note: This story is revised from the November/December 2013 issue of South Dakota Magazine. To order a copy or to subscribe, call (800) 456-5117.

Comments