The Gift of South Dakota

Subscriptions to South Dakota Magazine make great gifts!

Subscribe today — 1 year (6 issues) is just $29!

Ghost Town Friends

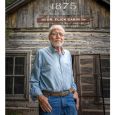

Editor's Note: We were sorry to hear that Black Hills historian and South Dakota Hall of Famer Watson Parker died this week at the age of 88. Long-time Hills residents might remember the Palmer Gulch Lodge dude ranch and resort near Hill City, operated by the Parker family until 1962. Parker and his wife Olga raised three kids in the shady pines there. He earned his PhD in history in 1965, taught at the University of Wisconsin-Oshkosh for 21 years, and gave expression to his love of the Black Hills in four books. The creation of one of them, Black Hills Ghost Towns, is described below, in a story from our January/February 2006 issue.

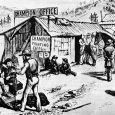

Watson Parker and Hugh Lambert published Black Hills Ghost Towns almost 40 years ago as a record of the myriad towns, stage stops and hovels that rose and decayed along with the boom and bust of the Black Hills gold rush. But their Ghost Towns is more than a coffee table book of interesting pictures and witty anecdotes. It is a valuable record of a vanishing history and a legacy to the enduring friendship of the two men who collaborated for over 17 years.

Like many Black Hills stories, this one starts with a family vacation. In 1937, Hugh Lambert’s family traveled to the Black Hills. While staying at Palmer Gulch Lodge, young Hugh fell in love with the Black Hills and met the innkeeper’s son, Wat Parker. They would become lifelong friends.

After Wat finished his daily chores, the two boys searched for abandoned mining camps. Their summer explorations left an indelible impression on Hugh. Even so, he would not talk to Parker again for 20 years.

Around 1957, Hugh Lambert decided it was time to return to the Black Hills. To his happy surprise, a call to the American Automobile Association confirmed that Palmer Gulch Lodge was still in business, and still run by the Parker family. It didn’t take long for Hugh and Wat to become reacquainted as they shared memories. Both observed that many of their stories would disappear as the towns and mines turned to dust.

|

| Dr. Watson Parker was professor emeritus of history at the University of Wisconsin at Oshkosh before retiring to the Black Hills. |

Rather than lament in nostalgia, the two decided to find and record the history of the surrounding ghost towns. Little did they know that they would work on and off for the next 17 years, gathering material for what eventually was published in 1974 under the title Black Hills Ghost Towns. Their book describes about 600 towns and sites that once populated the Black Hills region. A few of the places survive today, but most were already ghostly when Parker and Lambert began their project.

They divided the work. Parker researched the places in old newspapers, maps and the “musty books of history.” He also wrote the descriptions for sites featured in the book. Lambert located the places on the ground, using the opportunity to correct old maps and to draw up new ones, many of which appear in the book. Lambert also selected photographs for the book and wrote many of the captions. He supplemented the photographs with his own pen and ink drawings.

Parker and Lambert’s Ghost Towns goes a long way toward capturing and preserving many of the “history, ballads, yarns, legends [and] monuments” that give the Black Hills its own unique sense of place. A favorite handed down from Parker’s grandfather is set in Pactola, once a bustling mining area and resort, now under the waters of Pactola Reservoir:

At Pactola in years gone by there used to erupt a dance of quite considerable vigor, presided over by the indomitable Mrs. Bernice Musekamp. During Prohibition, Wat Parker’s grandmother arrived for a visit in the hills, driven, in those long-gone days, by her chauffeur in his natty uniform of boots, breeches and visored cap. It was in this outfit that Pace (that was his name) decided to attend the Pactola dance. Unfortunately for him the local populace mistook him for a revenue officer on the prowl, and a hurried midnight call from Mrs. Musekamp brought Pappy Parker to Pactola just in time to rescue Pace from the angry crowd that was about to lynch him.

The authors also tell about Gayville, named for Albert and William Gay, the latter of whom “achieved notoriety by killing a boy who delivered a flirtatious letter to his wife. He was sent to reside in the crowbar hotel for three years; he returned unrepentant and was welcomed back with a brass band. A dissident party who didn’t like the way William dressed — thought he would look better in a rope necktie — hoped to put him on a platform where everybody could see him, but they were in a minority and nothing was done about it.”

The book teaches without an ounce of pedantry but with plenty of dry wit. One good example is found in the caption that accompanies an otherwise nondescript photo of a cemetery near Harney:

They always built the cemetery on a point of rocky ground. Some say it was to get the departed nearer to heaven, and probably many of them needed all the help they could get. Others say it was to get off the wet valley floor, for no man in his right mind would want to spend eternity in a grave that wasn’t properly drained. But mainly they picked out the most ornery patch of ground there was, that nobody wanted, and made a graveyard out of it.

Parker and Lambert also teach us that Moskee in Crook County, Wyo. was taken from the Pidgin English “maskee,” meaning “no matter, never mind, I don’t care.” They share the lore that Mystic might have been derived from “mistake,” but suggest the more likely (but more mundane) version that it was named by a pioneer who hailed from Mystic, Conn. They explain that the origin of the name Two-Bit is much disputed, and could have been named for placers that yielded 25 cents in a single pan, or, for the more pessimistic, because a miner couldn’t get two bits worth of gold in an entire day. With tongue firmly in cheek, the authors tell us that Bare Butte was “an early name for Bear Butte. Captain Raynolds, exploring the area in the 1850s, took meticulous care to note that it was pronounced Bewt, to avoid giving offense to the delicate-minded.”

While the book has many lighthearted stories, it also captures the pioneers’ desolation. Describing Burdock, in Fall River County, the authors note that “one gets the impression that maybe the young folks held out there as long as grandma in her little cabin looking towards the mountains lived, but when she died, they folded up the store and headed for civilization.”

Only occasionally does a touch of nostalgia creep into Parker and Lambert’s writing. In discussing Rockerville, Parker and Lambert recount its development as a “real mining camp,” and “one of the roaringest.” The authors then ruefully describe how modern Rockerville became a tourist town, and note with palpable regret: “There are not many echoes in the Rockerville of today — the clink of coin, rustle of bills and click of cameras have drowned them out.”

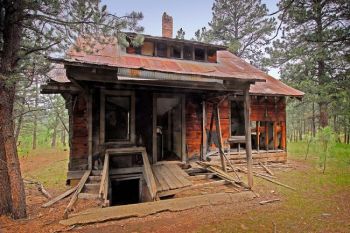

The book’s central theme is that “the ghosts of the past are where you find them.” The epilogue features a Parker story and a Lambert drawing as a monument to the lives that were lived in the harsh, rocky Black Hills:

Here lived the pioneers and built their hopeful towns, and here they nursed their frail ambitions only to move on, into the pages of history. These Hills and their past will come alive, though all around is in ruin and decay, if you will follow down the trails we have trod, see those strange sites that we have seen, and hear the tales that we were told…

Comments

One day Dr Parker brought in a small box to show the class. Contents of which was found laying on the ground, by the young junior historian, Watson and his brother. The item was obtained at the Custer battle field before being designated a National park. Tom Custer’s little finger, try doing that in these times of everyone being weak and offended.

s/f