The Gift of South Dakota

Subscriptions to South Dakota Magazine make great gifts!

Subscribe today — 1 year (6 issues) is just $29!

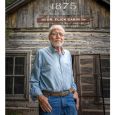

A Ghost Town Called Spokane

Editor’s Note: The mining town of Spokane, 16 miles northeast of Custer, was founded in 1890. The surrounding hills produced gold, silver, copper, zinc, mica and graphite. Mining proved profitable into the 1920s, but unfortunately Spokane met the same fate as did dozens of other Black Hills mining camps. By 1940 it was largely abandoned. Only remnants of its heyday still exist. Writer David Ford visited in the summer of 1990 and wrote this account for our May/June 1991 issue. It is illustrated with images by Spearfish photographer John Mitchell, captured in early 2019.

"It is said that there is a place on the small hill overlooking the old Spokane Mine, where on a moonlit night with the wind brushing softly through the pine trees, you can hear the miners clinging faintly to each other. As you listen to the wind, you can hear in it the faint sound of the miners working with picks hitting rock and see in the ever changing shadows, the dim outline of feathered Indians, fortune hunters, hard rock miners, loggers, rangers, and farmers driving their oxen, all passing by."

— From Rushmore's Golden Valleys, by Marthe Linde

I wasn't exactly sure where Spokane was. I just knew it was there. Four of us had been hiking up the overgrown road in the draw for about 20 minutes, give or take a few. You lose track of time in the Black Hills. It just doesn't seem as important as it does other places.

The first signs we found were scattered treasures of civilization: garbage, an oil filter, barrel hoops, and evaporated milk cans. The trash population increased as we climbed a rise on the left side of the road.

"Ssh, hear that?" I asked. Voices. Nothing you could understand, just muffled voices. Mixed with the voices was a sort of clanging — the kind of clanging one might hear in a factory or in a mill ... a mill that should have been quiet for a quarter of a century, at least.

I was the tour guide for our quartet of explorers, Judy, Ron, Marietta, and myself. I had hoped to have Spokane to ourselves so we could explore to our hearts' delight. It sounded as if we weren't the first here today. I figured I would find, just around a curve or over a hill, a bus load of picture-taking tourists from Japan or Boy Scouts from Chicago. Those guys seemed to be following us everywhere we went since we arrived in the Black Hills. But when we reached the top of the rise, all human noises stopped. There was no one there. No bus, nothing. The sounds of nature were still there — the birds and the rustling of the leaves in the trees. Nothing else. What else could there have been?

The first mine feature to be seen was the top of the headframe. The large stamp mill came into view beside the house and machine shop. Just think what it was like with the huge cables running from the hoist house to the headframe, lowering men down to work the mine and bringing up buckets of ore laced with gold, zinc, lead, and silver. On the north wall of the mill we found graffiti left by previous explorers. Now it is a sad part of Spokane history.

We followed a road that led through the mine buildings and down around the hill. It was a beautiful day and the hike was refreshing along the shaded lane. We rounded a last curve and a lush green meadow opened before us. It seemed to have been waiting for years for us to take in, or maybe to take us in. The road we were on circled the meadow so we circled with it. Foundations were now appearing on either side of the road. A basement here, what looks like a vault or cold cellar there. At one comer of the meadow another small road trailed off up the hill. It was littered with all types of garbage — fenders, stoves, and the ever-present evaporated milk cans.

At the head of the meadow, a two story house and garage stood guard over what we now realized had to be the townsite of Spokane. The house was deserted now but for how long has it been that way? It had a timeless quality about it. Further up from the house was a one-room schoolhouse. The steps were gone, as were the windows and the floor. Just like in a lot of other small towns, this school must have been used as a church. There seemed to be an energy about this building. Did it come from the pupils at recess or a teacher writing today's lesson on the blackboard? Maybe it was left over from some fire-and-brimstone preacher or the weeping of a wife and family who had lost a husband and father in some mine disaster.

As we left the schoolhouse I realized we were now speaking quietly and with reverence, a sort of new respect for the area we visited. This quietness continued as we took the road back to the stamp mill, the road that was the avenue to and from the mine for so many years. Every morning they marched up that road to work and every evening, home to their families. That was the key. We hadn't just left foundations and piles of garbage. We had been to see the homes of a community. A town that had once been filled with laughter and tears. A town that had felt the excitement of a gold strike and the fear of an Indian attack. The ruins hadn't changed but we had. Even though we had seen no one, I now knew we weren't alone. We had never been alone. We were surrounded by the spirits, the life forces of folks who had walked here before us. Indians, who had been here first, miners and their wives, farmers, shopkeepers, doctors, lawyers, undertakers, children and their teachers, and maybe now our little group. I could feel the ghosts of another time, not necessarily a better time, but different. It was a taste of life I hope to experience just a little of through my travels, my photographs, and now my writing.

The voices were always there, I just didn't know how to hear them. Now I know.

Comments