The Gift of South Dakota

Subscriptions to South Dakota Magazine make great gifts!

Subscribe today — 1 year (6 issues) is just $29!

Why We Fall for Balanced Rocks

|

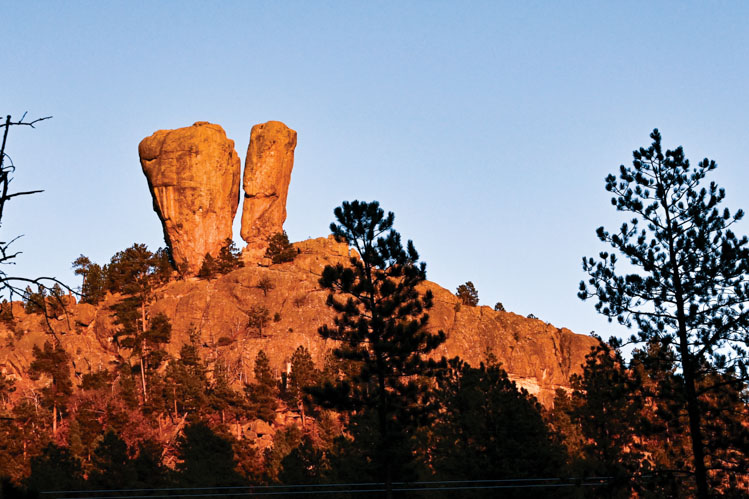

| Balanced rocks near Sylvan Lake. |

Ever since there have been poets, which is roughly the last 5,000 years, they have lauded the permanence of nature, and they might be right because Beecher Rock has stood on a mountaintop between the present-day towns of Custer and Pringle for perhaps 1.6 billion years.

The natural phenomenon of precariously balanced rocks (called PBRs in some scientific circles) not only fascinates poets but anyone who enjoys the natural world. Since the advent of human history, the fragile formations have served as guideposts and curiosities for travelers. They are studied, photographed, climbed, carved and sometimes intentionally toppled or dynamited.

All the above are true in South Dakota, where PBRs are most often found on granite peaks in the Black Hills. To learn more about the geological novelty, we sought out Perry Rahn and Kenny Hargens, two old friends who have been exploring the backcountry for decades. Rahn is professor emeritus of geology at the South Dakota School of Mines and Technology in Rapid City. Hargens has been hiking and studying the Hills ever since he was a boy, growing up across the road from the legendary poet Badger Clark.

We met Rahn and Hargens at the trailhead for the Mickelson Trail in Hill City, where the retired professor spread a large map across a picnic table and explained the geological history that created PBRs. “What we have here,” Rahn said, pointing to the buttes around Mount Rushmore, “is the old basement rock that was intruded by granite, exposing some of the oldest rocks on Earth.”

|

| Kenny Hargens (left) and Perry Rahn, pictured below Black Elk Peak, have studied and explored the Black Hills back country for decades. |

Rahn said the uplift was not a sudden eruption but a slow rise that continued for tens of millions of years as the earth’s crust was warmed by volcanic activity far below the surface. It caused strange rock pilings that would not have been visible because today’s canyons and valleys did not exist. However, another 20 million years of erosion by water, wind, snow and bacteria exposed boulders that had been stacked — sometimes precariously — by that ancient upthrust.

John Paul Gries, a predecessor to Professor Rahn at the School of Mines, noted in his 1996 book Roadside Geology of South Dakota that the original uplift happened about 58 to 50 million years ago. He wrote, “By roughly 37 million years ago, the Black Hills had much of their present size and shape. Hard rocks formed the ridges and plateaus, softer rocks became valleys and parks.”

The gradual erosion left so many balanced rocks — especially in the Sylvan Lake and Mount Rushmore range — that sightseers might take them for granted, especially since they share the terrain with a beautiful and dense pine forest.

Boulders, some as large as cars or trucks, are perched on the mountaintops surrounding Sylvan Lake, below Black Elk Peak. Though most are unnamed, one is called Guardian of the Pools due to its face-like appearance. It was popular on travel postcards a century ago. To people with some imagination, others could easily be seen as buffalo, dogs or frogs.

Hargens came across another “geological marvel” while hiking along Grizzly Creek in the Black Elk Wilderness Area, above Horsethief Lake. He found a 10-foot granite boulder stacked above another of similar size, both standing on bedrock. A smaller stone sat atop the two. Altogether, it reminded him of a gigantic snowman. Nearby was an outgrowth of rose quartz.

If the Snow Man, the Guardian and other Black Hills formations stood apart on a vast desert or prairie they might be better appreciated, perhaps enough to end up on a license plate or a postage stamp, like the iconic arches of Utah or Chimney Rock in Nebraska.

Arches are another category altogether, Rahn explains. “There’s lots of situations in nature that catch our attention. There are also leaning rocks and the wrinkled rocks near Mount Rushmore.”

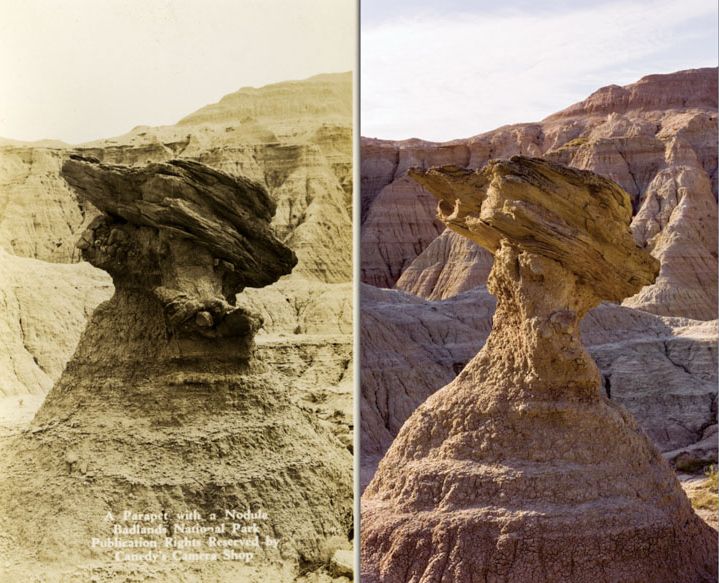

In the Badlands, toadstool formations (also known as hoodoos) are common. While toadstools appear to consist of a rock on a pedestal, they can be a single rock formation with a wide crown. Similar situations are found in the Cave Hills of Harding County. Rahn says he was sitting on a rock in the Badlands many years ago when he heard, “a sound like an earthquake. One of those pillars was falling to the floor.”

Three hundred miles east of the Badlands, in the land of pink quartzite near Garretson, a promontory stretches high above scenic Split Rock Creek in Minnehaha County. Locals call it Balanced Rock, though scientists would likely describe it as a pedestal spire.

|

| A pair of PBRs known as Beecher Rock north of Pringle. |

Rahn noted that unusual rock formations are rare in eastern South Dakota because that region was levelled by the Ice Age just 20,000 years ago. “The Black Hills was never glaciated, unlike eastern South Dakota where the continental glacier moved down over the landscape and smoothed it off. Here in the Black Hills this did not happen, so the weathering processes etched out these remarkable balancing and leaning rocks.”

Rahn and Hargens guided us southeast of Hill City to Sylvan Lake and Needles Highway. Rahn, ever the professor, could not walk for more than a minute or two without kneeling to identify a stone or pebble — rose quartz, mica, feldspar or tourmaline.

The shoreline of Sylvan Lake offers two interesting and picturesque examples of wedge rocks, yet another category of precarious formations. The easiest to find is above the far end of the trail which circles the lake. You can identify first-timers from frequent visitors because newcomers will look up, eyeing whether or not it’s safe to pass underneath. An even bigger specimen is near the trail, but harder to reach.

Sylvan’s wedge rocks are not likely to fall on you, but Rahn says PBRs will all topple eventually — tomorrow or 10 million years from now. “Once I was walking with a friend in Spokane Creek when I noticed the sand started to flow and before I realized what was happening the whole cliff came down on me,” he says. “I ended up in the creek with a few broken ribs.”

Rahn says most formations are gradually weakened by fracture joints. “Some of it is weathering and expansion. Maybe water gets in there and it causes an expansion when it freezes. There is also a chemical weathering where the feldspar slowly dissolves into clay and the rock crumbles away.”

However, humans have toppled more PBRs in the last century than Mother Nature. In 2016, pranksters pushed a famous formation known as the Duckbill onto the Oregon coast. Two years later, vandals shoved over the 320-million-year-old Brimham Rock in northeast England. A decade ago, a Boy Scout leader in Utah pushed a hoodoo to the ground in Goblin Valley State Park. He was sentenced to a year of probation for criminal mischief. Defacing natural sites in state or federal parks is a crime.

Fortunately, many of South Dakota’s PBRs are not as fragile as they may appear. Hargens led us to a ledge north of Pringle where twin spires known as Beecher Rock stand high above the forest. They appear precarious, but they aren’t likely to be toppled by man.

A Forest Service Road leads from Highway 385 to the western base of the 5,580-foot Beecher formation. Paul Horsted, an accomplished Black Hills photographer known for researching historical pictures, says Beecher Rock was visited by General George Custer and his expedition in 1874. They called it Turk’s Head, perhaps because from the south the twin rocks resemble faces with turbans.

Hargens says his father, Holland, once told him that he often climbed the ledge up to Beecher Rock with friends. “They would lay on their backs, he said, and when moving clouds passed above them, they got the sensation that the rocks were falling over on them.”

|

| Custer photographer Paul Horsted created a "then and now" scene of a formation called Parapet with Nodule that can be found on the Badlands Loop Road. |

Horsted says he has found teetering formations in the Grand Canyon, Yosemite, Acadia, Death Valley, Olympic and Yellowstone parks. “They are not uncommon, but they capture our imagination somehow.

“I think we like these formations because they defy gravity, and they sometimes look like nature couldn’t have made them. The Needles in the Black Hills might even qualify under that definition. These balanced rocks speak to geologic time as well,” Horsted says. “I think of how much time must have passed since that sandstone slab was resting on a hillside, which gradually eroded away around it, leaving the pedestal.”

While the formations have an aesthetic and poetic appeal, the concept of PBRs is also rooted in science. James Brune, a geophysicist with the California Institute of Technology, was studying earthquakes in Nevada when he recognized that the tenuous boulders provide a unique seismic history, telling a story in the way that tree rings do.

Today, many geologists and other researchers are continuing Brune’s work. They follow an unwritten code: never, ever knock a rock off its pedestal. Poets, photographers and all lovers of natural history share the sentiment.

Life is fragile enough, for people and for PBRs. Why not enjoy them while we can?

Editor’s Note: This story is revised from the January/February 2024 issue of South Dakota Magazine. To order or to subscribe, call (800) 456-5117.

Comments

We will be going in May so I need to know the activities happening in the Hills during that month.. Will your May Issue be out soon or could you send me a list of events during May. I will schedule our trip to conincide with things that look inviting.

Thanks much and keep up the outstanding journalism.

Doug England, formerly of Watertown, SD WHS Class of 57'