The Gift of South Dakota

Subscriptions to South Dakota Magazine make great gifts!

Subscribe today — 1 year (6 issues) is just $29!

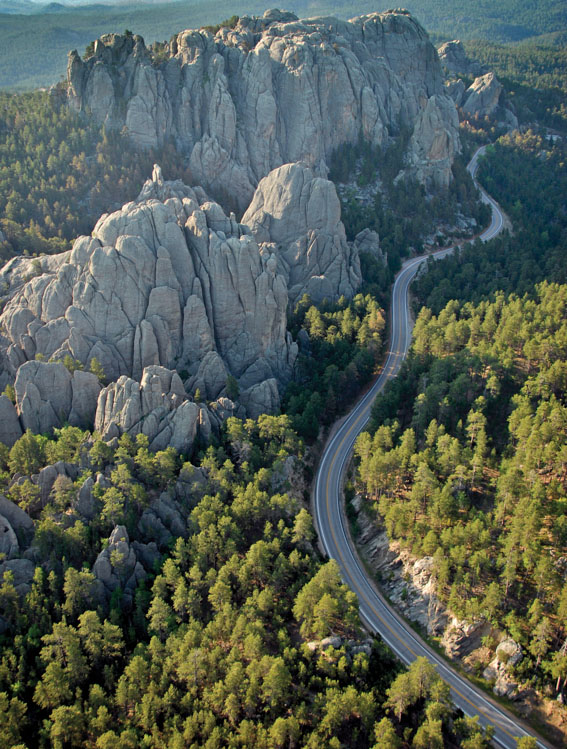

Blazing Trails

|

| Spiraling pigtail bridges make Iron Mountain Road an unforgettable drive. |

BECAUSE THE LANDSCAPES of the Black Hills are so beautiful, motorists don’t often pay attention to the road itself. That is a stirring testimonial to generations of roadbuilders who have bulldozed, dynamited and chopped their way through the mountainous terrain.

Black Hills roads wind through perennial rock (including some of the world’s hardest granite), dramatic elevations, and shape-shifting canyons — all obstacles that have been somewhat alleviated by the steady march of technology, bigger and sturdier equipment and technical schools with programs devoted to blazing trails through South Dakota’s remarkably diverse landscape.

However, the state’s most popular roads were built in eras when horses were powering the equipment, and the planners were mostly people who had little construction training. James O’Neill gets credit for Spearfish Canyon Highway, one of the state’s most loved scenic drives. Motorists climb 1,700 vertical feet over 22 miles through pines and aspens and under soaring rimrock, from Spearfish to Cheyenne Crossing.

O’Neill, born in Iowa in 1880, lived a childhood where poverty forced him to be adopted. His new family migrated west and he first experienced Black Hills stone as a young man, sharpening drills at Homestake Gold Mine. Later he established Spearfish’s first movie house, among other businesses, and won election to the county commission and as Spearfish mayor.

He was an advocate for the canyon road in the late 1910s or early 1920s. The first builders were mostly Spearfish men (sometimes including O’Neill wearing a nearly omnipresent fedora) equipped with picks, shovels and dynamite. When O’Neill was present as a hands-on leader, a tip of the fedora told the crew that a cigarette break was over, and it was time to hit the rocks. Later the Lawrence County Commission endorsed the project and supplied a tractor.

|

| James O'Neill, pictured at far left with his trademark fedora, oversaw this crew grading what would become the Spearfish Canyon Highway. The road eventually shared the narrow canyon with a spur of the Burlington Railroad until a flood in 1933 washed the rails away. |

Governor William Bulow spoke at the road’s dedication in August of 1930 and lit a fuse to ceremoniously blast “the last boulder.” In reality, the boulder was anything but the last. A highway built through a living, evolving canyon never escapes rocks, sometimes roiling with raging flood waters or tumbling from the rimrock. Damage from floods brought road builders back to the canyon many times, and to pave the highway in 1950. A destructive 1965 flood drew engineers who determined they could separate the highway from Spearfish Creek in strategic spots by cutting into canyon walls.

O’Neill lived to see many of those improvements. He also advocated for a long north-south federal highway through the Great Plains, from Mexico to Canada, and worked with like-minded representatives from other states in advancing it. The promoters celebrated in 1926 when sections of U.S. Highway 85 opened; South Dakota’s stretch enters the Black Hills between Lead and Newcastle, Wyoming. Not far across the state line from Wyoming, O’Neill Pass honors James, although mapmakers frequently misspell his name. Later, a spur called U.S. 385 took construction workers through many Black Hills geological zones ranging from sandstone and gypsum to ultra-hard granite as they built north from Fall River County to Lawrence County’s gold mining country.

Peter Norbeck — as a state legislator, governor and U.S. senator — worked to gain Americans access to the splendor of the Black Hills. Norbeck is considered the father of Custer State Park where, he believed, much of that splendor could be enjoyed through car windows if drivers moved at 20 miles per hour. After the park of mountains and pines and buffalo opened in 1919, Norbeck walked and rode horseback to see firsthand how automobile passengers might best enjoy the great granite spires of the Needles and the panoramic views.

*****

Always up for adventure, Norbeck in 1905 had become the first to drive from the Missouri River to the Black Hills, following nearly 200 miles of cattle trails and wagon roads. Skeptics mocked his developing Needles Highway, calling it the Needless Highway (after all, farmers wouldn’t use it for hauling produce to market, usually a priority when developing 1920s roads) and some engineers advised Norbeck that the route he liked was impossible due to the volume of granite. Norbeck scoffed, calling those trained engineers “diploma boys.”

|

| Highway 244, part of the Peter Norbeck Scenic Byway, winds along the backside of Mount Rushmore. |

Suzanne Julin, author of A Marvelous Hundred Square Miles: Black Hills Tourism 1880-1941, noted that Norbeck’s main interest was aesthetics. “Norbeck used his popularity, his political skills and his policy-making power to promote the construction of roads in Custer State Park that would tempt motoring travelers ….” His supporters noted that as a well-digger by profession, Norbeck knew practical engineering and how to cut into the earth. He soon encountered Scovel Johnson, a state engineer whose vision and spirit of adventure matched his own. Supplied with enough dynamite, Johnson told Norbeck, he believed the 13-and-a-half-mile highway would be completed in a matter of months.

Born in 1877 in Washington, D.C., Johnson was drawn west and to the far northwest by the mining industry. If Custer State Park visitors found the area thoroughly remote, he didn’t see it that way. Johnson had once been lost in the Alaska wilderness for three months. “He did so many things,” says history writer Dillon Haug, noting that in addition to mining and road building Johnson served as Custer County State’s Attorney. “In lots of ways he was mostly self-taught.” Johnson likely gained basic roadway engineering knowledge when he worked with Forest Service crews building early logging roads. That know-how would have included surveying, soils stability, drainage and geometry indicating whether vehicles could navigate curves as designed.

Highway engineers and contractors nationally were among the first to learn of the Needles Highway project because of a trade publication, The Highway Magazine. An unnamed writer visited during construction and was ready to report when the route opened in 1922. A “weird and beautiful road” the magazine called it, and a photographer showcased its hairpin turns. More than anything, the publication seemed impressed with what Johnson called Crevasse Tunnel (known today as Needle’s Eye Tunnel). It was cut, the magazine reported, “sixty-six feet through solid granite and is approached through a rock crevice 180 feet long, four feet wide and 70 feet deep, as left by nature, but now widened at the bottom so that cars may pass with safety.” Compressed air machinery was put to work, the article continued, so that an “average of 140 linear feet of drill hole was driven each ten hour shift.”

Compressed air drilling and dynamiting were standard operations in Black Hills hard rock mining and would shortly be adopted for shaping nearby Mount Rushmore. Along Needles Highway soon after its opening, state historian Doane Robinson studied the Cathedral Spires formation and decided to find a sculptor who could transform it into a giant carving depicting historical characters of the American West. Gutzon Borglum was drawn into the project but preferred U.S. presidents and a granite cap at Mount Rushmore, a few miles away. Long before carving ended in 1941, Mount Rushmore had proven itself a Black Hills attraction like none other. “The number of visitors recorded at Mount Rushmore increased from 108,000 in 1932 to 197,000 in 1935 and to over 300,000 in 1939,” wrote historian John E. Miller in his book, Looking for History on Highway 14.

In 1938 the Federal Writers Project’s Guide to South Dakota advised: “Hard-surfaced road to Memorial; sharp curves require careful driving.” That was U.S. Highway 16 linking Rushmore and Rapid City, a little less than 25 miles. After final sculpting and the end of World War II, annual visitation soared into the millions. “A close connection existed between the monument itself and building roads in South Dakota,” noted Miller. “Good hard-surfaced roads were a prerequisite for substantial tourist traffic.” South Dakotans preferred their tax dollars to be spent on highways, not mountain carvings, he added.

Private sector highway contractors gained the state a reputation for fine roadways. Chuck Lien, and Northwestern Engineering Company co-owned by Morris Adelstein and L.A. Pier, were Rapid City-based. In the Mount Rushmore state, sometimes road elements became art in their own right. An example is Wind Cave National Park’s Beaver Creek arch bridge, engineered by Morris Adelstein.

|

| A dam constructed on Rapid Creek in the 1950s created Pactola Lake, the largest and deepest reservoir in the Black Hills, as well as beautiful views for motorists traveling Highway 385 about 15 miles west of Rapid City. |

U.S. 16 saw major rebuilds across the decades because of traffic growth and business development near Rapid City. By contrast, U.S. 16A passes mostly through Forest Service land and its route from Custer State Park to Mount Rushmore is unique, to say the least. This is the Iron Mountain Road, roller-coaster-like in spots. Some drivers love it, some find it intimidating. No one forgets it.

A decade after Needles Highway, Iron Mountain Road was another Norbeck-Johnson project, a stunning route over and through a great granite ridge. Norbeck brought in C.C. Gideon, a Minnesota-born building contractor. Gideon had constructed Custer State Park’s game lodge and several other buildings there, then stepped into park leadership roles. His chief contributions to Iron Mountain Road were three pigtail bridges.

Those wooden structures solved a dilemma. Scovel Johnson, during design, realized Iron Mountain’s west face was so steep that he couldn’t engineer roadway switchbacks, as he had planned for the mountain’s other side. The pigtail design has the road spiraling under itself in tight circles. Meanwhile, three tunnels would be blasted (in recent years the tunnels were named for Johnson, Gideon and Doane Robinson).

Upon completion, Iron Mountain Road became the stuff of legends, some far-fetched. Did the builders complete the first tunnel and express surprise that it perfectly framed Mount Rushmore, and then decide the other two should, as well? That claim makes Gideon’s granddaughter, Marilyn Oakes, laugh. “I’m quite sure they had it all figured out before the tunnel work started,” she says. “They wouldn’t have started such a convoluted road without a very clear idea of what they were doing.”

Boulder Canyon and Vanocker Canyon highways. The Wildlife Loop. Argyle, Nemo and Tinton roads. The maze of Forest Service routes. People lost on foot in the Black Hills National Forest should remember that despite immediate appearances, they’re never far from roads to safety. That’s something Scovel Johnson, the Alaska wilderness survivor, stressed. Most roads serve multiple purposes, but were usually designed with specific tasks in mind, including timber hauls, mine access, firefighting, and bringing visitors within view of buffalo herds.

All drivers traveling on American interstates owe thanks to the Black Hills’ own Francis Case. Serving in the U.S. Senate in the 1950s, Case argued that if the proposed interstate system was to function as the national defense highway (its original purpose) then it had to link rural America to the nation’s urban centers. As a powerful member of the Senate Public Works Committee, Case successfully pushed for a federal gasoline tax so that sparsely populated states like South Dakota could afford their long stretches of highways.

|

| Black Hills roads, like this route through Custer State Park, follow the contours of the landscape, providing scenic views and safe travel. |

The Gustafson family’s road crews built 63 percent of the original I-90 between Sioux Falls and Rapid City. That, said David Gustafson, was under his father’s leadership. Today the younger Gustafson is president of Heavy Constructors, Inc. of Rapid City. It’s a modern builder of roads and other facilities that hasn’t forgotten its roots in the days of horse-drawn wagons and road graders. The company’s name hints at one way its road building has evolved. Equipment is massive and heavy indeed, powered by great engines.

“And computers changed everything,” Gustafson says. “With GPS, our dozers can almost do grading by themselves, although we still need people around with the old skills to double-check. Computers can make mistakes.”

Still, one can’t help but wonder whether today’s computer programs would have drawn plans for the roads we enjoy today. South Dakota’s mountain passages required a vision and a political savvy that probably can’t be captured in software.

Mike Vehle of Mitchell, who gained a reputation as an advocate of good roads during his years in the state legislature, believes the Black Hills’ historic roads warrant admiration. “I just got back from a trip to Croatia and their mountain roads make you appreciate ours even more. What they call a two-lane road is usually one lane, and if you move just a bit too far either way you are either over the edge or into the side of the mountain.”

Vehle chaired the State Senate’s transportation committee for eight years and was inducted in the South Dakota Department of Transportation’s Hall of Honor for his advocacy of better roads. He says the more he learned about South Dakota’s road history, the more he has come to appreciate Peter Norbeck and the other visionaries of yesterday.

Norbeck, the politician and self-made roadbuilder, once told his friend Francis Case that he would rather be remembered as an artist than a senator. Perhaps he succeeded. We’ve forgotten many of his other policies and programs, but we never tire of the roads he created.

Editor’s Note: This story is revised from the January/February 2023 issue of South Dakota Magazine. To order a copy or to subscribe, call (800) 456-5117.

Comments