The Gift of South Dakota

Subscriptions to South Dakota Magazine make great gifts!

Subscribe today — 1 year (6 issues) is just $29!

Ramming Through the Mickelson Trail

|

| The Mickelson Trail, a recreational trail built atop an old railroad bed. stretches 109 miles from the northern to the southern Black Hills, passing through forests, meadows, four rock tunnels and several old railroad trestles. |

Six hundred avid bicyclists and several dozen trailblazers met at a community hall in Custer last September to celebrate 25 years of happiness, no small feat in today’s anxious world. The gathering included participants in an anniversary ride along with current and former park officials, volunteers, donors, lawmakers and other movers and shakers who helped transform an abandoned rail line into what’s now known as the Mickelson Trail.

The state trail should not be taken for granted. A strange silence had settled over the Black Hills after Burlington Northern’s last train exited the mountains in 1983. The sound of engines echoing down draws was never pervasive, but the understated rumble was always a reminder that railroading helped build high country towns and industries — from Edgemont in the south to Lead and Deadwood in the north — and sustained them for nearly a century. The 109-mile rail corridor was a connection to the outside world that especially helped Homestake become America’s biggest and most technically advanced gold mine.

Three years after the trains departed, a man was walking through the forest when he heard a chain saw. He discovered that someone was cutting down an old wooden railroad trestle. Compared to locomotives, the buzzing of a saw cutting into a trestle in 1986 was more insect-like, but it disturbed the hiker so he contacted Guy Edwards, a young businessman and state lawmaker.

Black Hills activists were already talking about transforming the vacated rail bed into a recreational route under the recently authorized federal Rails to Trails program. Destruction of the rustic trestles seemed like a major step in the wrong direction. Edwards soon learned that the damage was not being done by vandals, but by a salvage contractor hired by Burlington Northern. A few dozen bridges had already been removed. The lawmaker arranged for demolition to cease until matters could be sorted out. Then he convinced state officials to make the trail a priority. So began a complicated, controversial and long-drawn out battle to create a rails-to-trail project.

“Probably 95 percent of property owners along the trail were against us at first,” Edwards told South Dakota Magazine many years later. “I could understand their position. After years of having trains go by their property, it appeared the corridor might meld into the landscape.”

|

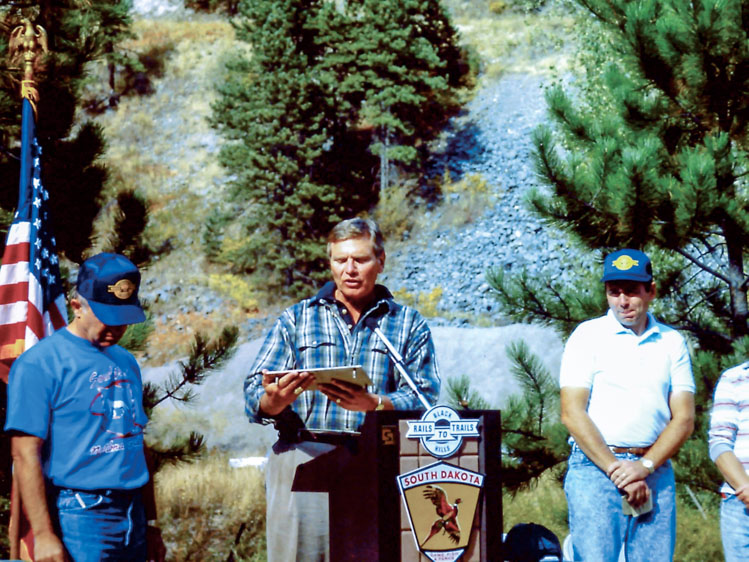

| The Mickelson Trail may not exist today if not for the zealous support of its namesake, Gov. George S. Mickelson, who presided over an early dedication ceremony before he died in a 1993 plane crash. |

The Interstate Commerce Commission had granted Burlington Northern permission to abandon its business of running trains through the Black Hills, but not the railway. The corridor had been established under federal authority because in the 19th century there had been an economic need, and under Rails to Trails it would remain in place in case another need arose. Meanwhile the public could use it for recreation.

In 1986, Brookings attorney George S. Mickelson ran for governor. He made a $50 donation during the fall campaign to a nonprofit organization set up to advance the trail. At the 25-year anniversary event last fall in Custer, the late governor’s son, Mark, reminisced about his dad’s approach to making things happen. “As governor, my grandfather (George T. Mickelson) was the only state official to show up for the first blast at Crazy Horse Memorial,” Mickelson said. “My father saw a parallel in how his own early support could help make the trail a reality. He loved the Black Hills and being out here.”

After taking office as governor in 1987, George Mickelson said he wanted trail work to commence at “ramming speed.” He used the train term metaphorically, but it did illustrate the work that lay ahead: trestle restoration, culvert development and surfacing the route.

The earliest obstacle was the hundreds of property owners who valued their privacy and were wary of sharing the back country with hikers, bikers and horses. Susan Edwards Johnson, who is Guy Edwards’ sister and was then Mickelson’s tourism secretary, spoke of the governor’s tenacity at the Custer anniversary gathering. She especially recalled a meeting at Mystic, where some cabin owners were personal friends and political supporters of the governor.

After listening patiently to their concerns, Mickelson rose to his feet and told the naysayers to get aboard because, “We are coming through!” Few politicians in South Dakota history ever had the political gravitas to lead so bluntly.

Later, Mickelson spoke of the opponents to Rapid City Journal reporter Jim Holland. “Treasures like the Black Hills are jealously guarded,” he said. “They have different ideas of what the Hills should be used for than we do. We will help to protect the qualities of the lands we both hold so dear. It may be impossible to get them to share our dream, but we promise to be good neighbors.”

“He saw it as a legacy project for South Dakota,” says Kitty Kinsman, who became involved with fundraising for the project in the 1990s. Opponents eventually softened — partly because of their respect for Mickelson, who offered to build private-access gates and fences for property owners to alleviate some of their concerns.

|

| The Mickelson Trail isn't particularly steep. Grades are generally less than 4 percent. |

Kinsman helped organize the anniversary event in Custer. She wonders whether the trail would exist without Mickelson, who was a strong conservationist. Just months before his death, he also persuaded lawmakers to pass his Centennial Environmental Act, a comprehensive program that continues to protect the state’s water and land resources. It’s hard to imagine such a proposal passing the South Dakota legislature today.

Along with the political hurdles came less contentious questions. And there were few models across the country to imitate. “It was an idea ahead of its time,” says Doug Hofer, former director of the state Division of Parks and Recreation, who also celebrated at the Custer event. No one doubted that trail sections close to Edgemont, Pringle, Custer, Hill City, Rochford, Lead and Deadwood would see use. But what about those long stretches far from towns? Would Black Hills weather, famous for rapid changes, scare potential users from venturing on the remote stretches? What about the growing mountain lion population?

Then, seven years into the project, Mickelson died in a 1993 plane crash with seven other men. His family directed memorial donations to the trail effort, but no amount of money could replace the leadership of the popular governor, who did everything in life at ramming speed. Eventually the route was named in his honor.

Hofer says the project seemed to benefit from “divine intervention” after Mickelson’s death. Capable people would appear to tackle aspects of development at just the right times. Among them was Dave Snyder, an ag businessman from Pierre and a member of a national Rails to Trails organization. Snyder contributed significantly to the project when he learned that $1 million was needed to match state and federal money, and he devised a plan based on the route’s trestles for raising the full amount.

More than a hundred trestles had to be rebuilt, decked and improved in other ways, and a value was assigned to each based on length. Private and corporate sponsors could “adopt” bridges for donations that ranged from $1,000 to $25,000. Snyder traveled the state, successfully pitching the bridge builder project.

“We had lots of bridges ranging from $3,500 to $5,000, although donors understood they weren’t buying that bridge, but rather matching dollars for the whole trail system,” Snyder says.

He also believed opposition would fade because that was the history of other trails. “There just aren’t incidents involving trail users,” he noted. “You don’t see trash. I tell people that nobody gets on the trail and then feels worse when they get off.”

With money available for construction supplies, Paul Bosworth of the U.S. Forest Service, among other duties, led National Guard men and women assigned to the work. Many were novices when it came to construction, but enthusiastic about the trail. “They were super fun,” Bosworth says. “Of course, this was part of their military training and sometimes they had to take a break when they were ‘attacked,’ grabbing guns and shooting blanks at guys playing the enemy.”

|

| The trail follows several meandering Black Hills creeks. |

Kinsman, who had never pedaled a mountain bike before she began working with Snyder and Edwards Johnson on the bridge builder campaign, now rides the Mickelson regularly. “I’m struck by both the scenery and solitude even when you’re not far from roads,” she says.

Today, 15 trailheads make it easy to jump on and off for short rides or hikes. Rest and shade areas and interpretive signs have been created. A 5-mile paved spur was developed by the state Department of Transportation to take users close to (although not into) Custer State Park.

It took governors, state and federal officials, private sector donors, volunteers and the Burlington Northern to complete the project. The full 109-mile trail opened to hikers, cyclists, runners and equestrians in 1998 — 15 years after that last train — and soon gained a reputation as one of the best Rails to Trails routes in the country. It passes through varied landscapes of forest and prairies, four rock tunnels, and, of course, over those trestles.

More than 20,000 people purchase $15 annual passes, and many more buy $4 day passes. Park officials believe more than 70,000 people traverse it throughout the year. The annual Mickelson Trail Trek, which celebrated its 25th year at Custer, is limited to 600 registrants; most years, the registrations are gone within 24 hours. A three-day Summer Trail Trek is now held in June to accommodate more people.

One of the trail’s many charms is the way it pops out of the pines and passes through small towns. Julia Monczunski’s favorite trail memory is running the 2006 Mickelson Trail Marathon. “Actually, I competed in the half-marathon, my first long-distance race, and it was neat to be running in the mountains and then ending in Deadwood,” she says. “I was tired but felt a burst of energy from the crowd cheering us on as we came into town.”

Monczunski, who has also raced on pavement, appreciates the Mickelson’s forgiving crushed limestone surface. Cyclists also like the control they feel with limestone on long downslopes. Trail developers say limestone is aesthetically appropriate to the Black Hills and less vulnerable to water damage during heavy rains.

Trail use continues to evolve. E-bikes are the newest twist. “They’ve made the trail more accessible, especially for people who aren’t adjusted to altitude,” Kinsman says. “They’re here to stay.”

|

| Nineteenth century railroad workers built the train corridor in about one year. Converting the path to a trail required 15 years. |

But they pose problems. Collisions with other cyclists happen when inexperienced e-bike riders stick to the center of the trail to maintain a sense of control. “It’s a nonmotorized trail and class one e-bikes have been seen as okay,” Snyder says. “But sometimes there are class two or even class three e-bikes out there, almost small motorcycles, and that has to be watched. And a 50- or 60-pound e-bike is probably okay, but maybe not one that’s a hundred pounds.”

Motorized bikes, mountain lions and even the weather don’t seem to discourage users. Online reviews are dominated by 5-star ratings. The most common complaint is the long ascent that runs south of Deadwood/Lead to Dumont.

The passage of a quarter century and the trail’s place in today’s Black Hills culture doesn’t mean the work is done. The corridor requires constant upkeep. Aging trestle decking will have to be replaced and at least one support beam has been infested by ants. The tunnels are monitored constantly for safety. There’s a spot where Rapid Creek — diverted from its original channel by railroad builders — acts up.

The Custer gathering honored six cyclists who have ridden the autumn Mickelson Trail Trek every year since 1998. Kinsman says it was also an opportunity to relaunch the Friends of the Mickelson Trail group because private donations are needed for the rehabilitation efforts.

Though the trail is part of the state park system, numerous agencies and individuals have always stepped forward to help. “I spent so much time working on the trail, and now when I go there and see people using it, having fun, it makes me happy,” Bosworth says.

Bosworth has been retired from the Forest Service for a few years but returns to the trail to help as a private contractor. “The trail did so much for me in launching my career,” he recalled, “that I’ll do anything for it.”

He’s happy that so many people now enjoy the Black Hills wilderness along the trail, and notes that the major concern of property owners today isn’t the hikers and bikers with whom they share the backwoods, but whether the private gates that give them easy access are in good working order so they can join them.

Editor’s Note: This story is revised from the March/April 2024 issue of South Dakota Magazine. To order or to subscribe, call (800) 456-5117.

Comments

Who would have guessed that the undergrad working for the BHSC (no U back then), newspaper and yearbook would still be finding great subject matter today. My pleasure to work with you then, and a greater pleasure to enjoy your work today.