The Gift of South Dakota

Subscriptions to South Dakota Magazine make great gifts!

Subscribe today — 1 year (6 issues) is just $29!

The Strangely Familiar World of Andrew Kosten

Dec 7, 2016

"I’m a basement dweller," says Andrew Kosten. And it's true. He banks major dwell time in the basement studio of his Brookings home, cranking out intaglio vignettes from the world inside his head.

From this world, strange, forlorn and fantastical characters conduit via pencil onto the pages of his many sketchbooks. Then his work begins. "I’m always making, always working,” he says. “I’m kind of the silent worker type, that’s just inherently who I am."

Printmaking through the traditional etching method is labor-intensive. “It’s a very physical process. That’s what I really love about the process is its physicality. That’s why I’ve chosen to make prints. I’ve been in love with the process since I first did it.

“I was a painter before I was a printmaker. I did still lifes. I had a fixation with objects and formal aspects of spaces and color relationships as they were represented in these still lifes.

"My work wasn’t really about a whole lot. It was just about painting. But I had a separate body of work in sketchbooks. People were like, ‘You need to be doing this.’”

The Memphis, Tennessee native took a printmaking class at Washington University in St. Louis and, like a printer's ink, he found a niche. “[The University of South Dakota] was put on a shortlist of grad schools to look into. Initially I was like, ‘South Dakota?’ And I put it on the bottom of the list. I visited Vermillion and I was attracted to the calm and the spaciousness. I could tell this was like going off somewhere and just focusing on your work. I was able to get a lot done there.”

He studied under Lloyd Menard, the legendary longtime instructor-artist and Frogman's Print Workshop founder, in his final years at USD. After grad school, Kosten took turns at several teaching posts before settling in Brookings, where he lives with fellow artist and partner Diana Behl.

Kosten's art seems to draw more from an inner well than his adopted home, though you can find elements of prairie solitude in his work. “I think I’ve absorbed the sense of openness, the open spaces — the idea of mapping your observations. Spatially there’s a way the work has opened up in a way that’s new for me. Whether or not you can attribute that to the locale I don’t know.”

There's a whimsical reminiscence in his work, though one that seems to recall the bygone days of another dimension. But maybe that's memory. Whether the pining kind, or even the good-riddance variety, images of the past are altered in the mind's eye by time and subconscious agendas.

The characters from Kosten's world might seem familiar to you, though it’s hard to articulate why. “I’ve always been an avid collector. Going back to my childhood, I’ve had collections of things that were more about a fixation or fascination with that particular object and the feelings or nostalgia they evoked.”

A first-generation Sony Trinitron delivers vivid aperture grille TV technology to his studio. In a hobby room off his studio he has a collection of box turntables, cassette decks and curly-cord analog phones. "Much of what influences my work is the experience of the every day and how I can mix that in to this dark and comical world I create in some of the imagery."

The dreamy tonal quality of his prints is an effect of the aquatint technique he uses in parallel with the traditional etching process.

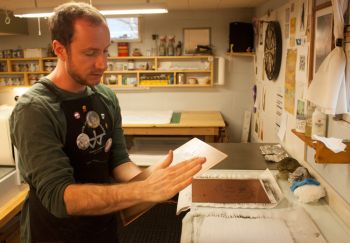

He starts with a drawing and a clean copper plate, coating the plate with a waxy, acid-resistant ground. To create the aquatint effect, he applies rosin to the plate, heats the rosin for an evenly distributed coat, and then uses a scraper tool to create varying gradients of shade.

He scratches the drawing into the ground with an etching needle, then gives the plate an acid bath that etches lines into the areas where the ground has been scratched away.

After the plate has been etched and the ground wiped away, ink is applied and finds its way into the areas etched beneath the surface. The plate is wiped down again, then run through an etching press, which applies pressure to transfer ink from plate to paper. The paper is then hung to dry. Each additional color, if any, requires another run.

Every step in the process is meticulous, and some are time-intensive. But in the process is where this basement dweller hits his stride. "I can isolate myself and get deeper and deeper, so I’ve got to maintain that healthy regimen of getting out and being exposed to art and artists."

One way he interacts with other artists is through exchange portfolios. A group of artists each sends a print to the person putting together the folio. Then they send each artist a complete set of prints by each participating artist. When we visited, Kosten was printing an edition of 25 two-color prints for an exchange.

The print — inspired by something an adolescent Kosten glimpsed across the Lake of the Ozarks at summer camp — is a nice introduction to the hazily dreamlike quality of his work. Do you have some recollection of this place but you're not sure how? Dive a little deeper.

Michael Zimny is the social media engagement specialist for South Dakota Public Broadcasting in Vermillion. He blogs for SDPB and contributes arts columns to the South Dakota Magazine website.

Comments