The Gift of South Dakota

Subscriptions to South Dakota Magazine make great gifts!

Subscribe today — 1 year (6 issues) is just $29!

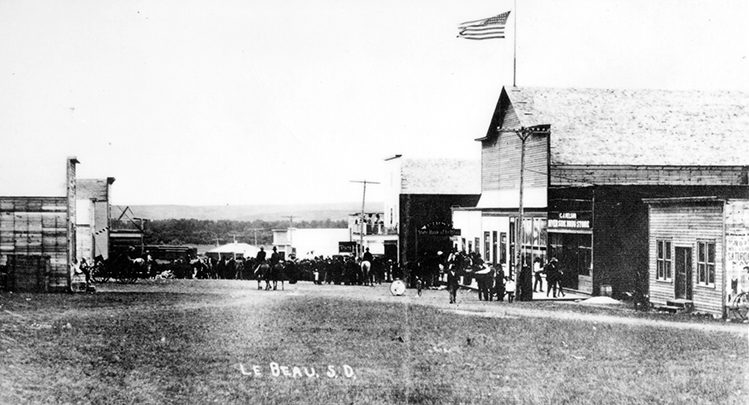

Frontier Phantoms

|

| LeBeau began as a fur trading post in 1875. When the federal government opened reservation land across the river to catle grazing, LeBeau swelled to a cattle-shipping town of 500. |

When the waters of Lake Oahe recede, bits of nearly forgotten history emerge. Among the settlements and towns consigned to watery graves by Missouri River dams is the notorious town of LeBeau — the town a gunfight killed. We climb into Tom Houck’s muddy Ford pickup truck at the ranch house west of Akaska, where four generations of his family have lived, for the 4-mile pasture trip back in time.

We bounce down a well-worn trail through the Houck ranch with Tom and his wife, JoAnn, cross the Minneapolis and St. Louis Railroad grade through a cut, and ford Swan Creek, where killdeer and yellowlegs clatter up from the creek bed and red winged blackbirds shriek warnings from nests amongst the reeds. In the narrow skirt of brushy trees along the water, a brown thrasher sings his inimitable song to his mate.

Back up on the rolling plain, western king birds dodge for insects, and a meadowlark’s seven-note song pierces the blue from a clump of grass. Overhead, an immature bald eagle circles, chased by a red-tailed hawk. We top a hill, and Lake Oahe spreads before us, a glossy sheen. We cross from ranch to Corps of Engineers land and roll downhill toward the river.

Houck brakes the pickup to a stop well above the shore. He points to a lone elm tree near the edge. “That’s where they planned to build the school,” he says. “They got the foundation laid, but then the town began to die. They never got it built.”

We climb out and walk toward the water’s edge. “When Oahe is full, the shore is 1,618 feet above sea level, up about here,” Houck says, his arm sweeping a strip of tall, dense weeds. “Now it’s 1,580 or so, down 35 feet.” We stroll past green depressions, ringed by scattered stones. “Those are the cellar holes of homes,” he says. He points north to a cut where locomotives rounded the bend and chugged along the river shore to cattle pens.

|

| Tom Houck stands on the sidewalk of LeBeau's First State Bank during a year of low water on the Missouri River. |

JoAnn picks her way gingerly, watching for rattlesnakes. Ahead lay remnants of main street LeBeau. Wind-driven waves lap the shore, covering, then revealing foundation stones of the First State Bank. Red bricks from the long-gone factory at Akaska are strewn about the shore. A wide concrete sidewalk slopes toward the water and disappears.

LeBeau’s disappearing act began in 1909, at the ripe old age of 34.

Antoine LeBeau, of French and Lakota parentage, opened a fur-trading post on the Missouri’s eastern bank in 1875; within a decade the frontier town grew to 200. In 1904, the government opened the Cheyenne River and Standing Rock Sioux Reservations across the river for cattle grazing, and LeBeau’s future seemed secure. Cattlemen from Texas and elsewhere moved in, and in 1906 the Minneapolis and St. Louis Railroad arrived to haul the cows to market. Impromptu houses grew up the hill, swelling the town to 500 people.

Those were the glory years of LeBeau, 1906 to 1909. Glory years if you mean the Hotel LeBeau was heated by steam, that there were banks, cafes, general stores, doctors and lawyers, a newspaper, even a pair of churches and an opera house. Glory years if you mean that thousands of cattle grew fat on native grass, money flowed, saloons and gamblers prospered. At its peak, the Scotland-based Matador Land and Cattle Company fattened tens of thousands of steers on half a million acres of reservation land it leased from the federal government for 3.5 cents per acre. When steers were ready to travel east, cowboys drove them into giant holding pens on the west bank of the river and ferried them across on the Scotty Phillip.

LeBeau was not the kind of town where Murdo MacKenzie wanted to live, but it had been a good place to extend his cattle empire. MacKenzie could run the Matador from his mansion in Trinidad, Colorado, but he needed a manager in South Dakota. He sent David, his son.

Like many a rich man’s son, David, or Dode his friends called him, had a talent for spending his father’s money. And he had a penchant for drink. After an all-night binge, Dode MacKenzie and a drinking buddy, Ambrose Benoist, staggered into Phil DuFran’s Angel Bar the morning of Dec. 11, 1909 and ordered drinks. Nobody knows exactly what words passed between the pair and bartender Bud Stephens, but what is known is that MacKenzie crossed the street to Knoll’s hardware, picked up a .45 Colt revolver and a handful of .38 cartridges, loaded the gun and headed back across the street to confront Stephens. The bartender pulled out his own .44 and fired point blank at Dode MacKenzie’s chest.

|

| Cattlemen conducted business by day in LeBeau, but they could grow rowdy inside the Angel Bar, where Bud Stephens killed Dode MacKenzie. |

The trial was held in March of 1910, in the county seat town of Selby. The jury consisted mostly of farmers, who spared little love for big-time cattlemen and their hard-living cowpokes. The jurors bought Stephens’ claim of self-defense and found him innocent of murder or any other crime.

Dode MacKenzie may not have been popular with the men who rode the range, but he was a cowboy, like them. They blamed LeBeau for his death. The Matador moved its operation north, a blow to the town’s economy. And in September, six months after Stephens’ acquittal, LeBeau burned down. Nobody could say how the fire began, but volunteer firemen found their hoses cut. One of the few buildings to survive was Phil DuFran’s Angel Bar.

Perhaps LeBeau could have risen from the ashes, even as its foundation stones still rise on occasion from the Missouri. But other factors intervened. Pro-sodbuster President William Howard Taft had replaced the cattlemen’s friend, Theodore Roosevelt, in the White House. Homesteaders were flooding the territory, and cheap leases of Indian land were about to end. The drought of 1910 was breathing down their necks. The Minneapolis & St. Louis train even derailed east of town.

Ellsworth LeBeau grew up on the Cheyenne River Reservation in the 1950s, and later served as president of the tribal college in Eagle Butte. He inherited the stories of his ancestor’s town, and as a child visited LeBeau before the waters rose. All that remained even then, he says, was sidewalks and foundations and the remnants of cattle pens.

“Antoine was my great, great, great something on my father’s side,” Ellsworth said. In the early days, Antoine and a brother also cut wood at Four Bears, south of the Moreau River, to supply fuel for steamboats that docked at LeBeau. They were paid in guns, ammunition and clothing, Ellsworth said. Antoine helped organize Walworth County, and held county offices for years. In old age he crossed the river one last time, and is buried on the reservation.

In the town’s early days, Indians crossed the river for LeBeau’s Fourth of July parade and celebration, Ellsworth said. “The cowboys were a pretty rowdy bunch.”

Today, rowdy cowboys and others still view Bud Stephens’ .44 in the Walworth County Courthouse in Selby. Crumbling bricks from the short-lived town lie on mantels and stand as bookends in area homes. JoAnn Houck treasures the photographs she took of LeBeau’s remains in 1963, and again 40 years later when water was low. Across the Missouri on the Cheyenne River Reservation, cattle still graze. Birds still nest and feed and sing. But when the waters of Lake Oahe rise once more, LeBeau will recede again into the depths of memory.

Looking for Grandpa at LeBeau

By Tom Keller

My great-grandparents, Harry and Grace Keller, had stores in Egan and Flandreau around the turn of the century. Harry heard about the booming cattle-shipping town of LeBeau, and decided to start a store there.

I’d heard the stories of the long-gone town south of Mobridge since I was a kid.

When Dad had visited LeBeau in the low river year of 1952, the front step of Harry and Grace’s store was still there, with “H.E. Keller” carved in concrete.

|

| Tom Keller found his grandfather's name etched in the concrete of old LeBeau. |

Last fall I decided to see LeBeau for myself. I got vague directions from Akaska, and met my folks on a Saturday morning. There’d been a little snow, and the last few miles of road were dirt. Half way in, my venerable Volvo hit a rock. I got out and watched oil pour from the damaged pan onto the ground. I trudged to the top of the next hill with my cell phone to arrange a tow. The folks waited in the car while I walked west, I hoped toward LeBeau.

The trail diverged into three options, and I had no idea where I was going. I reached the edge of Oahe, but found no LeBeau. No relics. No steps. No sunken town. I hiked up and down the shoreline, and finally gave it up; of course, I didn’t know exactly what I was looking for.

I was almost back to the disabled car when a Corps of Engineers pickup appeared on the horizon. The government man was there to protect the shore from looters. But he had already talked with my parents, and knew my intent. He’d been to LeBeau, of course, and didn’t recall the concrete steps I sought, but he volunteered to show me what was left of the town.

We found a horseshoe-shaped sidewalk, buckling from the bed of the receding lake. We found the imprint of the concrete manufacturer, but no front step of H.E. Keller’s general store. I took a few pictures, and we speculated about life in LeBeau. We had turned to go when my companion said, “Hey, what’s this?”

And there it was.

I was like a kid who’d followed a map to treasure in a secret cave. It was just a slab of century-old concrete, but it still clearly bore my grandfather’s name. I finished off my roll of film.

Back in Sioux Falls, I dropped off the film for developing. When I told the woman my name, she asked where my family was from. She was curious, because her name was Keller too.

“My dad’s family is from Huron,” I said, “but he’s an only child and his dad was an only son, so we don’t have a lot of relatives around. Where’s your family from?”

“Up by Mobridge,” she replied.

Editor’s Note: This story is revised from the March/April 2004 issue of South Dakota Magazine. To order a copy or to subscribe, call (800) 456-5117.

Comments

I still have the chair