The Gift of South Dakota

Subscriptions to South Dakota Magazine make great gifts!

Subscribe today — 1 year (6 issues) is just $29!

Lakota Games on Ice

|

| The Rosebud's Mike Marshall is an expert in Lakota winter games. |

From the frozen shore it looks like a game of hockey on Lake Mitchell. Youth and adults are bundled in coats, gloves and scarves. But is that a rib bone flying across the ice?

Actually, it’s the Lakota Games on Ice, a project of the Mitchell Prehistoric Indian Village to explore the region’s earliest Native cultures. “Sliding the buffalo rib” is a contest to see who can shove a winged bison rib the farthest. In pte heste (buffalo cow horn sliding game), kids slide an arrow-like gaming piece across the ice with a focus on distance and accuracy. Napeoglece kutepi teaches throwing a willow spear, and pasloghanpi tests accuracy while sliding a stick on ice.

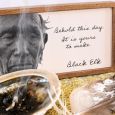

Mike Marshall, an artist, cultural entrepreneur and enrolled member of the Rosebud Sioux Tribe, oversees the games and even makes the gaming pieces. Marshall became interested in the project several years ago when he worked at the Buechel Memorial Lakota Museum in St. Francis, where he helped to digitize a collection of Native American objects that included historic gaming pieces.

Marshall creates the equipment for the Lakota Games on Ice out of bison bones and other objects of nature. Centuries ago, such games were often held in winter because that’s when Native Americans would set up camp. Girls tended to play games that taught how to pack, move and raise camp. Boys played games that taught hunting or fighting skills.

Lakota author and teacher Delphine Red Shirt wrote stories about the games that were passed on to her orally. In her book Turtle Lung Woman’s Daughter, she recalls her grandmother’s words. “She had her group of girl friends who played together. They stayed in small groups and took short walks around the camp or went swimming together in the summer. They played and imitated the women, doing everything they did,” she wrote. “They gave mock feasts and tended to dolls carried in cradle boards, singing songs to them and braiding their hair in neat braids.” They did not play with boys. “We ignored them,” she said. The boys had their own games. “Theirs was a male world, filled with play on horses and games of aggression.”

During the treaty period, many games were banned along with long hair and braids, traditional dress and language — part of a process to force Native Americans to assimilate with the predominantly European cultures that had settled in the United States. But visitors to the reservations recorded the existence of the games a century or more ago, and many of the gaming objects were housed in private collections.

Cindy Gregg, executive director of the Prehistoric Indian Village, says her organization strives to promote an understanding of the first people to inhabit the region. Lakota Games on Ice fits the mission, as do exhibits within the Boehnen Memorial Museum, which includes a reconstructed earth lodge and bison skeleton. More than 1,500 students and teachers from South Dakota, and as far away as North Dakota and the Twin Cities, tour the village and displays each year, including many Native American youth.

The village hosts other events throughout the year to help preserve and celebrate all facets of Native American culture. “The village provides visitors with an in-depth view of pre-white culture on the Great Plains,” Gregg says. “In doing that, it also helps foster a deeper appreciation for the current Native cultures on the reservations and elsewhere.”

Visitors also learn more about prehistoric agriculture and lifestyles. Occupied more than a thousand years ago by hunters and farmers who migrated out of the Mississippi River Valley, the village is believed to have been built by ancestors of the Mandan. More than 70 earth lodges are buried beneath the village, on the banks of Lake Mitchell. On the nearby golf course is a series of burial mounds, one of which covertly underlies a gently sloping green.

Archaeology Awareness Days, held in conjunction with an annual excavation by Augustana University and the University of Exeter in England, takes place under the village’s state-of-the-art Thomsen Center Archeodome. The ongoing excavations have unearthed bone, pottery and tools, as well as hundreds of 1,000-year-old small, charred corncobs and sunflower seeds. Those and other discoveries are evidence that the original village is directly linked to today’s common food products, as well as the corn that adorns the nearby Corn Palace.

“The occupants of this site played a significant role in the continuum of agricultural development that originally started in Mexico and moved up the Mississippi River Valley,” says Jerry Garry, a longtime Mitchell resident and one of the early organizers of the effort to preserve and develop the village as a living educational tool. “Today, because of these people, we enjoy many of the cereals that are consumed worldwide.”

Too often, today’s media focuses only on the historic crises of Indian country rather than the contributions and accomplishments of its ancient cultures — including their playful spirit. “What’s really cool about Lakota Games on Ice is that it makes us more than just a romantic notion,” says Marshall. “We had our games and leisure activities.”

Editor’s Note: The 2021 Lakota Games on Ice is scheduled for Jan. 23. This story is revised from the January/February 2017 issue of South Dakota Magazine. To order a copy or to subscribe, call (800) 456-5117.

Comments

Again, Thank you for the article.