The Gift of South Dakota

Subscriptions to South Dakota Magazine make great gifts!

Subscribe today — 1 year (6 issues) is just $29!

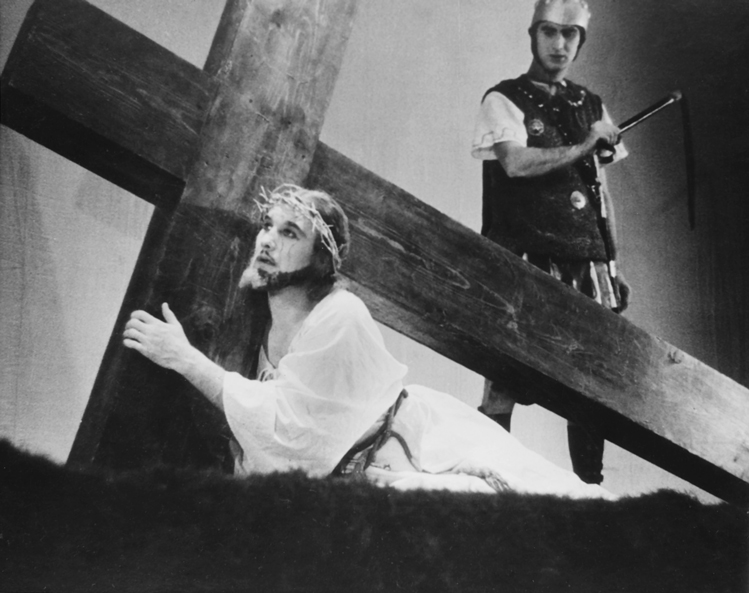

The Man Who Played Christ

|

| Josef Meier brought his Passion Play to Spearfish in 1938. |

So overpowering are the accomplishments of the man who played Jesus Christ that it's sometimes hard to remember the individual behind them.

Popes honored Josef Meier three times for the religious inspiration he brought to millions. Meier was the Cal Ripken of theatre, his record 8,000 performances of a theatrical role unmatched in American stage history. And he was the very image of the immigrant who comes to the United States with very little, lives every day in celebration of American freedoms, and in so doing builds not only a livelihood but also an institution.

He did all this based in Spearfish, where in 1938 he transplanted an Old World passion play, a drama recounting Christ's last seven days on Earth. It can be added to Meier's accomplishments that he pioneered Black Hills tourism, putting his play in a town with no railroad. Tourism was still the domain of railroads in the 1930s, but Josef Meier correctly guessed that would change.

Of course, Meier's mystique is enhanced by the fact that most photos show him costumed as Christ, the role he played 8,000 times for a total audience of 9 million people. But digging through Spearfish files one uncovers other pictures, such as Meier dressed in work clothes and a western hat, his beloved horses and dogs at his side.

A year after Meier's death in 1999 at age 94, interviews with his family, friends and Passion Play actors revealed an individual every bit as remarkable as his honors and records, though he always downplayed those, explaining that the Passion Play's message was important, not its numbers and awards.

One longtime Spearfish friend said, somewhat sheepishly, "I find I can't talk about Josef Meier without quoting him, because he was such an articulate man. And I can't quote him without imitating that wonderful German accent of his. So I imitate him, but with the utmost respect."

Charlotte Carver, first South Dakota Arts Council executive director, recalled Meier as "a gallant gentleman. He possessed a true continental charm."

Indeed he did, and a knack for winning lifelong friendships. At one point the Meiers' Christmas card list numbered 6,000, He especially liked friends who held up their end of lively discussions about most anything: politics, the South Dakota cattle industry, the arts, the best spots in the Black Hills to find deer during hunting season.

Plenty of Spearfish people also recall Meier as a tough negotiator, who knew his play made a huge economic impact in Spearfish (it brought 4.5 million visitors to town during his lifetime) and who expected the community to help promote it and maintain quality roads to the amphitheater. At the same time, he'd do most anything to help the town move forward. He established scholarships at Black Hills State University, served on Spearfish's first hospital board, sacrificed some of his own property to make certain Interstate 90 got routed to town, and contributed time to civic projects through the Lions Club and Knights of Columbus. Meier never saw Spearfish until age 33, and then his play kept him away for months almost every year. But there could be no doubt where he considered home.

|

| Nine million people saw Josef Meier portray Christ in the Passion Play. |

It was a home far from his native Lunen, Germany. Born in 1904, one of nine children, Meier gained an academic knowledge of the English language in school. He was a serious student who considered a career in medicine, loved competitive swimming and developed a deep appreciation for literature, music and theatre arts.

''I'm not sure if he was serious about a medical career by the time he was a young man or not," said his daughter, Johanna. "At any rate, whatever his other interests might have been, his love of the theatre took over."

So much so that at age 27 he boarded a ship bound for New York, part of a troupe that would stage the 700-year-old Lunen Passion Play, in German, to American audiences. Their idea was to play cities with large German immigrant populations. The players found some appreciative audiences in 1932, but Meier quickly saw that a better plan would be to translate the play into English. After doing so, he based the play in Chicago and began hiring American actors as the original cast drifted back across the Atlantic. He eventually toured to more than 600 cities across the United States and Canada.

On the road during the Depression, the cast sometimes outnumbered the audience. Seldom-used auditoriums often required hours of maintenance before scenery and lights could be rigged. The cast traveled by rail; once their poorly heated car sat through a cold Oklahoma night, waiting to be picked up by a freight train. That misadventure sent one actor to the hospital with pneumonia, and prompted Meier to buy a fleet of trucks and cars.

|

| Josef and Clare Meier toured 600-plus cities and towns. |

"I found that good actors are often not good drivers," Meier said years later. "But we never had an accident that resulted in serious injury."

In the early years, Meier once told The Saturday Evening Post, "I worried over so many things. I worked hard all day on the play, and then sat up half the night struggling with letters and other paper work. It seemed a hopeless struggle, until one night in the middle of the play as I spoke the lines to Judas, 'Do you not worry about the tomorrow.' It struck me that it was about time I took my own advice. I worked just as hard afterward, but I haven't worried since."

Things improved further after Chicago actress Clare Hume joined the cast. She and Meier were married a year later. She took over costuming responsibilities and played Mary, Christ's mother.

Clare Meier recalled when the Passion Play came to Sioux Falls in late 1937. Among performances there was a memorable one at the state penitentiary, where the cast dressed in cramped prison cells. Sioux Falls businessman Leo Craig met the Meiers and learned that Josef one day hoped to find an outdoor venue for the production. Craig suggested the Black Hills, where he owned a cabin. Meier had already investigated possible sites, including the Ozarks, where the scenery was beautiful but the mosquitoes thick. He liked a Santa Barbara amphitheater, but not the ocean fogs that would surely cancel performances.

The play came to Spearfish in late summer of 1938 for a few performances at the college auditorium. Before Meier and his company left town, the Lunen Passion Play's name had been changed to the Black Hills Passion Play. Spearfish photographer Joe Fassbender shot publicity photos, and builder Martin Thompson said he'd have an amphitheater constructed to Meier's design specifications by the next summer. Mount Rushmore sculptor Gutzon Borglum welcomed Meier to the Hills, and the Borglums and Meiers became close friends.

Spearfish banker Walter Dickey topped Josef Meier's list of people who made the Passion Play a South Dakota success. When the cast moved into its amphitheater for its opening performance June 18, 1939, it was the talk of the Hills. According to the Spearfish newspaper, 27 dates that summer drew 35,000 people. But in 1940, with most residents having seen the production and Black Hills tourism still in its infancy, attendance fell sharply. A local Passion Play corporation, which had built the amphitheater and was responsible for its upkeep, folded. Josef Meier personally assumed the corporation's debts, and Dickey told him he could repay a bank loan as he was able.

Keeping the production afloat wasn't Meier's only interest in those years. Johanna is certain that Spearfish's western setting was a reason her father settled there.

|

| Meier relaxing with two of his many dogs. |

"He grew up loving stories of the American West, and suddenly he had an opportunity to live here and have horses and livestock," she said. "He acquired a ranch, and he was much more than a gentleman rancher. I remember driving across the state with him, buying bulls, and he spent long days calving, vaccinating, and doing everything else a rancher does."

Meier’s ranch stood out because of its camels, which he used in the play. He learned that two-humped Bactrians from cool regions of Asia weathered South Dakota winters well.

Had the Passion Play failed, would Josef Meier have been content as a South Dakota rancher?

"He loved everything about ranching, but I'm not sure he could have done only that," said Johanna. "He had a charisma that needed a public outlet."

During the Second World War, Meier's public outlet became national in scope. Wartime travel restrictions shut down Black Hills tourism almost completely, but South Dakota's congressional delegation helped Meier secure fuel for far-reaching national tours. In 1942, the Black Hills Passion Play ranked as the second largest box office draw among road shows in the nation. Some cast members spent the summer of 1943 growing victory gardens in Spearfish before embarking on a tour that saw sellout crowds in Denver, Kansas City, New Orleans, Philadelphia and Washington, D.C. Time wrote that the Black Hills actors had scored "a solid, urban success." Performances resumed in Spearfish in 1948, and the production, now nationally known, attracted 50,000 people for the first time in 1952. By 1966, attendance had grown to 100,000.

Meier spent a lot of time during those years supervising amphitheater improvements, transforming it into one of the best equipped in the world, a theater which accommodated 6,000 in stadium-style seats. As he made his rounds, a dog or two usually accompanied him. (He once owned seven Great Danes and nine dachshunds; he was a soft touch for strays of any breed). While most Black Hills people knew him as a leader in local tourism, few knew he held the same reputation in central Florida, where another amphitheater went up in 1952 for annual winter and Easter season performances. Meier beat Walt Disney to central Florida by nearly 20 years.

Just because he staged the play thousands of times didn't mean he let it coast. He constantly reminded actors playing Jewish priests and scribes to think of their characters not as villains, as in some passion plays, but as educated religious leaders who feared their people would be punished by the Romans if Jesus proved too popular. Harold Rogers, one of the original actors who came to Spearfish in 1938 and who later became the play's general manager, recalled many nights when he and Meier sat in the amphitheater after performances, talking about problems audiences didn't see, but which rankled Meier.

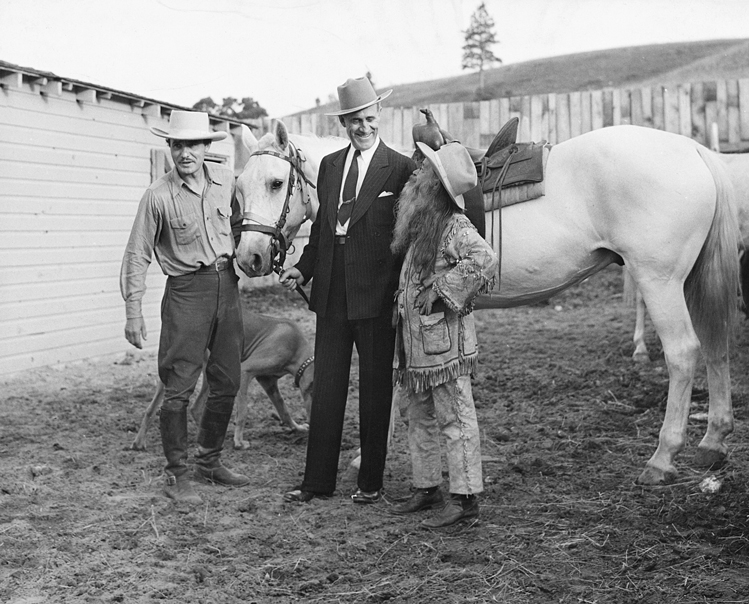

|

| Gov. Harlan Bushfield, center, met Josef Meier and Potato Creek Johnny in the early 1940s. |

His interest in the arts extended far beyond his own production, said Charlotte Carver. "He sat on the first South Dakota Arts Council, about 1970. I was executive director and he was a tremendous asset. At the same time, Charlton Heston was on the National Endowment for the Arts board. I told people I worked with Moses in Washington, D.C., and Jesus in South Dakota. You can't do any better than that."

Meier was an arts council asset because, just as he saw problems in his play no one else saw, he also saw opportunities no one else saw. And he envisioned charitable auctions for the arts that others didn't, and could bring them to fruition. For example, in the early 1950s, he met world-renowned opera singer Marjorie Lawrence in Chicago. Her career had been interrupted by polio, but she got back to the stage and Meier saw her perform. Like so many others, Lawrence was captivated by that charisma and continental charm, and before long she was in Spearfish, performing the first of two amphitheater benefits for young South Dakota polio patients.

Late in his career, so many plaques and lifetime achievement trophies came Meier's way that the family lost count at about a hundred. One that meant a great deal was the Bundesverdienstkreuz, West Germany's highest civilian honor. West Germany paid tribute to a South Dakota actor and rancher for two reasons — because he helped keep a piece of German heritage alive in the New World, and because after the Second World War he helped rebuild a Lunen church that had been shelled.

However busy Meier might have been during the war, taking one of America's biggest road shows from city to city, he never let Germany slip from his mind. In a eulogy, nephew Heinz Meier remembered treasured wartime packages that came to German family members from South Dakota containing Spam, chocolate, colorful American neckties, shoes, and even concealed contraband cigarettes and coffee.

Josef Meier turned the Passion Play over to Johanna and her husband, Guido Della Vecchia, in 1991. He and Clare traveled, splitting each year between Spearfish and a lake home in Florida. In South Dakota, he drove to the ranch outside Spearfish regularly, and there was also time to catch up on some reading — his taste ranging from political history to German classics to Zane Grey westerns.

Thirteen months after Meier's death, the first Passion Play performances of 2000 were staged on the road, in a Hamilton, Ontario coliseum. Once again the production that is Josef Meier's legacy proved its staying power, drawing capacity audiences and winning critical acclaim. "It's spoken with elegance and certainty by a commanding company of actors," a Hamilton Spectator reviewer wrote, " ... taking us away from mundane daily concerns."

Backstage between matinee and evening performances — an environment of costume trunks and electrical cables and penned camels that Meier knew well — the cast gathered around a table of sandwiches. Seven of the performers once worked for Josef Meier. During their meal, they shared memories: Meier's precise direction, his love of experimentation with special effects, his disdain for laziness or complacency.

No one spoke more poignantly than Charles Haas, a Florida actor portraying Christ. "He sparked something in me that made me a better person," Haas said. He is forever grateful for Meier's guidance when he was in his 20s, playing the disciple John. In the middle of the Spearfish season, Haas' parents were killed in a car crash.

"Mr. Meier told me life is movement," Haas said, "that you have to keep your thoughts going and your body active through difficult times, and live in the present. Regardless of tragedies and obstacles, he believed we all have a responsibility to use whatever gifts and talents we've been given."

That is the spirit that built the Black Hills Passion Play.

Editor’s Note: This story is revised from the July/August 2000 issue of South Dakota Magazine. To order a copy or to subscribe, call (800) 456-5117.

Comments