The Gift of South Dakota

Subscriptions to South Dakota Magazine make great gifts!

Subscribe today — 1 year (6 issues) is just $29!

Reaching New Heights

|

| Paul Horsted (left) and surveyors Jerry Penry and Kurt Luebke conducted what they believe to be the first accurate survey of Black Elk Peak in nearly 120 years. |

Standing inside the stone fire lookout tower atop Black Elk Peak on a crystal-clear day, a person can see hundreds of miles across South Dakota, Wyoming, Nebraska and Montana. You feel like a king surveying his realm. You’re standing on the highest point in South Dakota, the spot long touted as the tallest between the North American Rocky Mountains and the European Pyrenees along the border of France and Spain. If you have a map, it will say you are 7,242 feet above sea level.

But that map is wrong, according to surveyors Jerry Penry and Kurt Luebke, who in the fall of 2016 took a team of volunteers and conducted perhaps the first accurate survey of the historic mountain in more than 100 years. Over the course of two days, using equipment and methods that didn’t exist when the United States Geological Survey last triangulated a handful of high points in the Black Hills in 1897, the team concluded that Black Elk stands 7,231 feet high, 11 feet shorter than the widely known and accepted elevation.

Black Elk’s measurements have differed since man first tried to assign it a number in the late 19th century. Sometimes the discrepancies came in hundreds of feet. Even modern estimates differ based on the particular points considered. The highest natural rock? The top of the stone lookout tower? The tip of its lightning rod? Some other prominent point?

Penry chose to conduct his survey to the highest natural rock, so with equipment in hand on the morning of September 15, 2016, he and the team began their ascent.

*****

The birth of Black Elk Peak began more than 1.8 billion years ago, when a vast pool of molten magma cooled and solidified below the earth’s crust. It rose with the Black Hills Uplift, which began about 62 million years ago. By around 30 million years ago the uplift had ceased, and erosion left much the same landscape that we enjoy today.

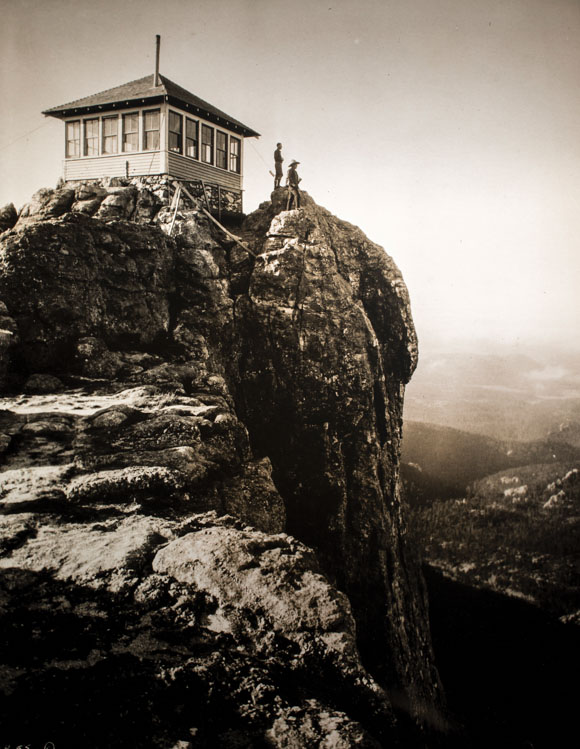

|

| The first structure placed atop Black Elk Peak was little more than a small table placed there in 1911 to spot wildfires. The Forest Service later built this wooden lookout, which has since been replaced by the stone tower that we know today. Photo by Charles D'Emery/Paul Horsted Collection |

The first white men to try to ascertain its height were members of Lt. Col. George Armstrong Custer’s 1874 expedition into the Black Hills. Custer and his 7th Cavalry had been sent from Fort Abraham Lincoln near present-day Bismarck, North Dakota, to scout potential fort locations and to investigate rumors of gold in the Hills, which remained within the Great Sioux Reservation under terms of the Fort Laramie Treaty of 1868.

Having established camp at the present townsite of Custer, a small party escorted by a company of cavalry left on the morning of July 31 to explore what the soldiers already knew — and what was already appearing on crude maps of the region — as Harney Peak. Lt. Gouverneur K. Warren had bestowed that name upon the mountain in honor of his commanding officer Gen. William Harney, known then for his battles against Plains Indians including the Grattan Massacre in 1854 and the Battle of Ash Hollow in 1855, in which Harney’s troops destroyed the Brule leader Little Thunder’s village along Blue Water Creek in western Nebraska, killing about half of his band’s 250 members. It was precisely because of his reputation for violence against Native Americans that tribes in 2016 successfully lobbied the U.S. Board of Geographic Names to rechristen it Black Elk Peak in honor of the Lakota holy man Black Elk (see sidebar).

Custer was accompanied by Newton Winchell (geologist), Aris Donaldson (botanist and correspondent for the St. Paul Pioneer Press), chief engineer William Ludlow and Ludlow’s assistant William Wood. After an 8- or 9-mile horseback ride along Laughing Water Creek and around Buckhorn Mountain, the party left their animals to scramble up the final 200 feet of Harney’s granite. “Wedging ourselves into the clefts, and pushing ourselves up after the fashion of chimney sweeps, clinging to projecting points and straddling over ridges, we at last reached the top,” Donaldson reported in the Pioneer Press.

It was then, however, that someone noticed an even higher point, and a higher point after that. The party scaled until finally they could climb no more. They had reached perpendicular granite walls that stood nearly 40 feet tall and could not be negotiated without ropes or ladders. “Prof. Winchell made the attempt and partially succeeded, but a loose rock just above him made it dangerous to climb higher,” Donaldson wrote. “He stood above us all.”

Ludlow carried a barometer, which he used to calculate the peak’s elevation at 9,700 feet. The following year, in 1875, the U.S. Geological Survey dispatched the Newton-Jenney Party to create a map of the Black Hills. Astronomer Horace Tuttle took measurements using a Green’s mercury barometer, considered among the most accurate tools available in the late 19th century for calculating elevations. Tuttle compared his readings on the mountaintop to another barometer inside the Union Pacific Railroad station in Cheyenne, Wyoming, where a precise elevation was previously established. By comparing the differences in readings, Tuttle concluded Harney Peak stood 7,369 feet high. Noting the incredible disparity between his reading and Ludlow’s from the previous year, Tuttle measured again, this time arriving at 7,368 feet.

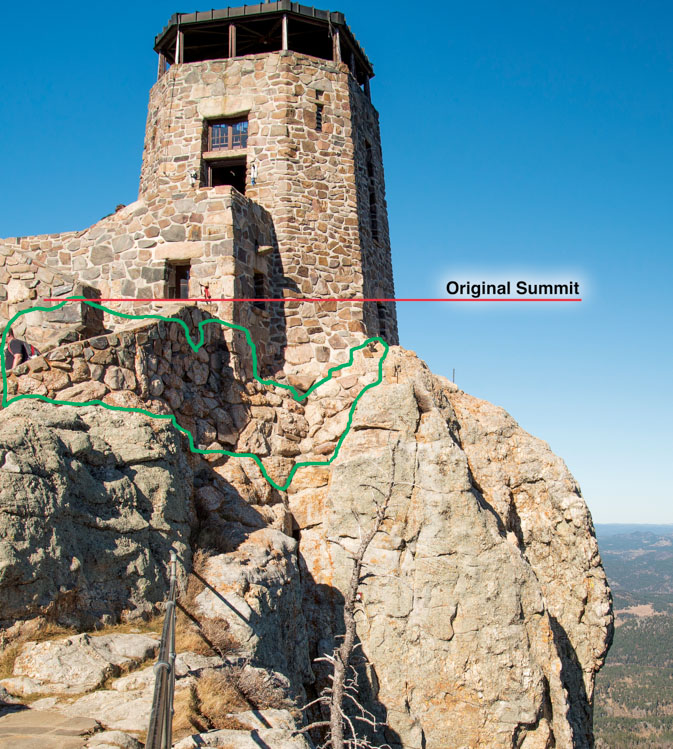

|

| Rock highlighted in green was removed during construction of the stone tower in the 1930s. Photo by Paul Horsted |

It’s worth noting that the original “true summit” of Black Elk Peak may not be the location of today’s fire tower. Valentine McGillycuddy, who worked closely with Tuttle as topographer on the Newton-Jenney Expedition and lived a long and influential life that shaped Rapid City and the Black Hills, selected what he considered the highest point on a spire about 100 yards south of today’s widely recognized and well-traveled summit. “Setting up and leveling it [the transit], we [McGillycuddy and Tuttle] swung the telescope to every point of the compass and Harney Peak — the rock our instrument was on — topped every other bit of granite, near or far!” McGillycuddy later reminisced. “It is possible that the Forest Service has selected a more accessible peak to designate as their Harney Peak station, for not many people have succeeded in making that ascent of the original and only Harney.”

The subsequent years were beset with confusion about the mountain’s true elevation. In 1877 the U.S. Geological Survey of the Territories published its latest edition of Lists of Elevations. Harney Peak was included at Ludlow’s 9,700 feet. Results from the Newton-Jenney Expedition weren’t published until 1880. Other travel publications indicated the elevation at anywhere from 7,440 to 7,700 feet. Tuttle’s result didn’t appear in print until the U.S. Geological Survey’s bulletin of 1891.

Then in 1893 the USGS created the Black Hills’ first triangulation network in which points were placed on selected peaks, including Harney. That was followed in 1896 by creation of the Deadwood Datum. Officials determined that a benchmark at the Deadwood depot of the Fremont, Elkhorn & Missouri Valley Railroad offered the most accurate sea level elevation in the Hills. From that point, hundreds more permanent benchmarks were established. A triangulation station was placed on Bear Mountain, just over 10 miles west of Harney Peak, and another on Crow’s Nest Peak, 16 miles northwest. Penry believes elevations were transferred from nearby benchmarks to these triangulation stations since they were easily accessible. The point that had been placed atop Harney in 1893 was easily sighted from both of those locations, which is most likely how crews arrived at a new elevation of 7,240 feet. The intervening years have added another 2 feet, leading to the 7,242 feet that appears on most maps, websites and other documentation.

*****

Paul Horsted has admired the view from atop Black Elk Peak dozens of times. The promontory and its recognizable fire tower have featured prominently in his photography since he and his wife Camille Riner moved to Custer 22 years ago.

Horsted found his niche in exploring 19th and early 20th century photo sites of the Black Hills and other spots around South Dakota and re-photographing them. His book Exploring with Custer, written with Ernest Grafe in 2002, follows the trail of that 1874 expedition and includes images taken by the expedition’s photographer, W.H. Illingworth, paired with Horsted’s modern-day versions.

|

| Horsted helped take measurements atop McGillycuddy Peak. Photo by Daryl Stisser |

Horsted became particularly interested with the geography around the summit of Black Elk Peak and what he came to think of as the nearby McGillycuddy Peak while studying photographs taken during the Newton-Jenney Expedition of 1875, including one image which portrays Tuttle and McGillycuddy surveying from this alternate summit. Noticing changes in the rock over the years, he learned of the differing elevations and contacted Jerry Penry, hoping to find a definitive answer.

Penry, based in Lincoln, Nebraska, has been a surveyor since 1984. Licensed in Nebraska and South Dakota, most of his work involves determining legal boundaries and property lines. But surveying is also a hobby. He began traveling to the Black Hills in 2010 to meet friend and fellow surveyor Kurt Luebke, of Missoula, Montana. Together, they spend vacations searching the Hills for old benchmarks and other monuments from the early days of surveying.

Penry was immediately intrigued by the elevation mystery. “I couldn’t come up with a definitive reason that that elevation existed on Black Elk Peak, so I really got curious,” Penry says. “There is no documentation that says someone actually had measured up to that peak to determine that elevation (7,242), but it did appear on some of the earliest maps of the Black Hills that the U.S. Geological Survey produced in late 1890s. As near as I could tell, they did it by triangulation from different points placed on mountain peaks. By turning angles both horizontally and vertically you can determine distances from point to point and also the elevation.”

So on a breezy but beautiful September morning, Penry, Luebke and Horsted ascended Black Elk Peak hoping to come away with a true elevation. They were accompanied by Daryl and Cheryl Stisser of the Sylvan Rocks Climbing School and Horsted’s wife and daughter, Camille and Anna Marie Riner.

The job combined using historic benchmarks with modern technology. The crew sought out two geodetic marks placed in 1934 along the present-day Mickelson Trail. Utilizing those, they created a new benchmark in an open area where global positioning devices could accurately be used. Then they headed up the mountain. Over two days — using levels, lasers, prism rods, advanced GPS transmitters and receivers and a lot of trigonometry — they came away with what Penry believes to be “the most precise survey ever done on that peak, I’m sure.”

The results were: 7,231.32 feet to the highest natural rock on Black Elk Peak near the stone lookout tower; 7,257.20 feet to the top of the tower; and 7,262.30 feet to the tip of the lightning rod mounted on the tower’s roof.

|

| Inside the lookout tower, surveyor Jerry Penry (with level instrument) and Paul Horsted transferred the precise elevation from an outside point. That helped determine the floor and roof elevations. Photo by Paul Horsted |

They also measured 7,229.41 feet to the highest natural rock remaining on McGillycuddy Peak. Studying 1875 photos of that area, Horsted says a block of granite about the size of a small car once jutted from the top but has since disappeared. “I think McGillycuddy was correct that it was a slightly taller area at the top of the peak,” he says. “Most people hiking by will wonder what the big fuss is about, but I want to give McGillycuddy his due as a topographer. He took this really seriously, and I do believe that he was correct in his view that he was on the actual summit of what he knew as Harney Peak.”

An interesting postscript to the measurements is that they will all change once again within a year. The 2016 elevations were calculated using the North American Vertical Datum of 1988, a leveling network that spans the continent. When the National Geodetic Survey updates the datum to rely solely on information gleaned from satellites in 2022, all elevations in the Black Hills will drop 2 feet, shrinking Black Elk Peak to 7,229 feet.

*****

Though the survey was completed nearly five years ago, maps today are still likely to read 7,242. That’s because both Penry and Horsted recognize that any official change could be a long and arduous process. “I didn’t really pursue it through a lot of channels, but it should be known,” Penry says. “I spoke to a few people in the Forest Service. It’s on so many documents, and it’s just been copied from one place to another, so I’m not real confident that it would ever be changed.”

“It’s just been fascinating and fun to know that the elevation has probably been incorrectly stated for more than 100 years,” Horsted says. “I’ll leave it to Jerry and Kurt to try to convince the powers that be that they need to update the maps, but that’s going to take years. It’s not unlike the name change. It’s difficult to erase something that’s been written down hundreds of times. So it’s going to be a while.”

Nevertheless, South Dakotans can still delight in a hike to South Dakota’s highest spot. The air remains clean and refreshing and the view just as inspiring — even if you’re only 7,231 feet high.

Editor’s Note: This story is revised from the March/April 2021 issue of South Dakota Magazine. To order a copy or to subscribe, call (800) 456-5117.

Comments