The Gift of South Dakota

Subscriptions to South Dakota Magazine make great gifts!

Subscribe today — 1 year (6 issues) is just $29!

The Judge

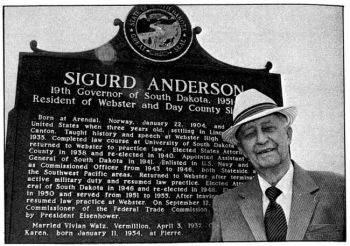

Editor’s Note: Sigurd Anderson’s rise from a young Norwegian immigrant who couldn’t speak English to governor of South Dakota is inspirational. We interviewed Anderson at home in Webster in 1988, two years before he passed away.

Whenever the Anderson family went to Canton for supplies, young Sig had two favorite haunts: the corner drug store, where he read everything but prescription labels, and the Lincoln County courthouse, where he sat enchanted by verbal battles between country lawyers.

That love of the English language might seem surprising, since he was born in Norway in 1904 and came to South Dakota at the age of 3 with his parents. He couldn't speak a word of English when he started country school. Even though there were many other Norwegians in the area, it seemed that he and brother George were singled out for teasing because they dressed differently. And even though they quickly learned English, the words came out with a distinctive Scandinavian brogue.

"One song I listened to a lot," he laughs today, was, "Oh, the Norwegians and the Dutch, They Don't Amount to Much."

Little did the other kids know that their quiet, immigrant classmate would become South Dakota's 19th governor.

Despite some teasing, and an occasional walk home across the cornfield to avoid confrontations, the Anderson boys adjusted. Their father, Karl, loved life in America and took his children to local political debates, where Sig received more exposure to fine oratory. He still remembers a Non-Partisan League debate in Canton where Gov. Peter Norbeck and Tom Ayres heated up the stage.

Eventually, his dress and speech became Americanized, and by the time he graduated from Canton Lutheran Normal School he was awarded a scholarship in debate from State College in Brookings. Scarlet fever cut his first college try short. After a stint as a hired hand on a farm, followed by a year as a country school teacher at Bancroft, he enrolled at the University of South Dakota in Vermillion where he became a good scholar, top debater and student council member.

He graduated with honors in 1931 and got a teaching job at Rapid City. But when school funds were embezzled by a local official, jeopardizing teacher salaries, he moved across the state to Webster and began a lifelong affair with Day County.

Sig returned to USD in 1935 to get a law degree. When he graduated, his goal was to return to Webster and establish a law practice. But he kept getting interrupted. First it was World War II, where he served as a legal officer in the Navy. Then, upon his return to Webster, he was persuaded to run for Attorney General. That followed two terms as governor, 10 years as a Federal Trade Commissioner, and eight years as a circuit court judge. Between almost every career change, he returned to Webster to try to get that law practice going.

Considering his love for Webster, it was not surprising that when he finally retired in 1975, he chose to stay right there, in the modest, two story white-frame house that he's called home for many years.

He still keeps a second story office downtown — a place to stack his books and occasionally hang his hat. But mostly, the office has been a great excuse to put on his trademark suit and tie and walk down Main Street, where everyone greets him as either "governor" or "judge" or just "Sig." This is his town. You get the feeling that they might even like to rename it for their graying favorite son. Andersonville? Sigtown?

But it won't happen. Sig would be the first to object. He'd note that there would be too great an expense involved in redoing the road signs, maps and directories, not to mention the poor business people who would need to toss out all their Webster stationary and envelopes.

The county commissioners did name a room in the courthouse after him. Located adjacent to the county museum, it will be a showplace for some of the former governor's photographs and memorabilia.

Until recently, he has enjoyed excellent health in retirement. However, at 84 years of age, he had a setback last winter and we visited him at the Day County Hospital, where we found him chipper and anxious to get back downtown. You can't practice law from a hospital bed.

About all you can do in a hospital is tell stories, and that's what he did.

He relishes the early days in politics. Soon after graduating from law school, he ran for State’s Attorney in Day County. Although the county is traditionally Republican, it had temporarily swayed to the Democratic side of the ballot due to Roosevelt's New Deal.

Sam Buhler, a legendary political leader in northeastern South Dakota, was GOP county chairman. He rallied the Republicans by holding over 40 events in country schoolhouses throughout the county.

His Democratic opponent was a friend and former roommate, Lyman Melby. Both were nervously anticipating the early returns on election night. Finally, word came that the Oak Gulch precinct totals had arrived at the courthouse. Melby and Anderson and other candidates ran to the auditor's office, where it was announced that for State's Attorney, the results were: Anderson, 29; Melby, 29.

Oak Gulch didn't launch his political career, but the other precincts gave him a victory. He was re-elected two years later, and before serving the second term he was appointed Assistant Attorney General in Pierre. Then, after four years of service as a legal officer in the U.S. Navy during World War II, he returned to Webster. Friends urged him to run for Attorney General. War veterans make good candidates, they explained, and he even had experience in the office.

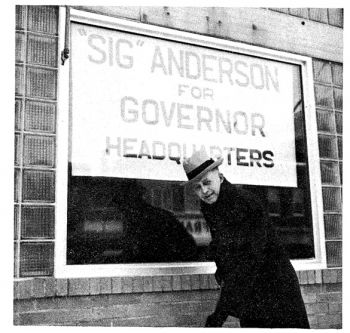

Again postponing plans to get that Webster law practice established, he entered his name as a candidate.

Sig's four years in the attorney general's office were highlighted by a "Stamp Out Crime" program that was popular everywhere except, perhaps, in Deadwood, where main street entrepreneurs occasionally forgot that the Black Hills were not located in Nevada.

"We burned up a lot of slot machines in our day," he says. "And we prosecuted a lot of people."

He remembers a day when law officers carted an especially ornate and fine-crafted roulette wheel out of Deadwood tavern and lined it up with other gambling devices to be burned. A lady proprietor, appreciative of the craftsmanship, pleaded with Anderson to spare the game of chance. "That lady stood there and cried as they burned up the machine," he says.

If he were in office today, he says, he would be strongly opposed to the new lottery program. "I really think we don't need gambling as a source of revenue in South Dakota."

As Attorney General, it was Anderson's responsibility to witness South Dakota's only state execution when convicted murderer George Sitts was led to an electric chair in the Sioux Falls penitentiary on April 8, 1947. "It was a rainy night, dripping outside, just the way the book said it should be," recalls Anderson. "I walked in and there was Sitts. My, what a muscular fellow. He had been a stunt man in a circus. I said, 'George, how are you.' He said, 'Not so bad, under the circumstances.' We shook hands."

Anderson said officers then put a hood over Sitts’s head and led him into the execution room, where he was strapped to the chair. The warden asked the prisoner if he wished to make a statement before they proceeded. "Warden," said Sitts, "this is the first time the police have helped me out of jail."

Then, recalls Anderson, there was a "Swish! Swash! Smell!!! And it was over." Sitts was pronounced dead.

Sig calls it "the big one." Of all his elections, nothing compares with the 1950 battle for the governorship. Again, both parties wanted qualified war veterans. The GOP contest became a five-way race, with Sig and war hero Joe Foss eventually rising to the top.

Foss was a World War II flying ace, a recipient of the Congressional Medal of Honor who downed 26 enemy planes. He campaigned by plane around the state, a tactic that not only speeded his travels but also was a constant reminder of his achievements.

"Every time a plane flew over, a little kid would say, 'Hey, that's Joe Foss up there,'" laughs Anderson. "No one had any battleships for Anderson."

Sig campaigned hard. He and his wife, Vivian, left Pierre each day after work in their Chevrolet coupe, grabbing only a few Hershey bars for nourishment, and traveled from town to town. People liked the gentlemanly, soft-spoken Attorney General. And he was a natural campaigner. He had a command of the language, knew the issues and hardly ever forgot a name.

Most people felt that none of the five candidates would get the required 35 percent majority, and that a nominee would be selected at the state Republican convention. But Anderson narrowly crossed that threshold, and became the nominee.

His Democratic opponent in the fall was Joe Robbie, a young attorney who went on to become owner of the Miami Dolphins. As a Democrat, Robbie was the immediate underdog. Voter registrations then favored the GOP by a three to one margin. Republican gatherings drew much larger crowds, and Robbie was desperate to get his message out. He started an innovative attack of challenging Sig to a debate at almost every stop. He even brought along a chair for his "absent" foe. He'd tell his audience, "That chair is for Sigurd Anderson. He refuses to debate me."

Anderson, now a skilled orator, was anxious to debate Robbie. But any such idea was vetoed by friends and supporters. "Are you cray? Ignore him!" they told Anderson.

The strategy worked. Using his lowkey, friendly style of campaigning, he won the election by 55,000 votes. Two years later, he was re-elected by a plurality of 203,102 votes.

The boy who couldn't speak English when he started school was governor of South Dakota.

Though in years since it has become a cliche, Sig really did treat state government like a business. When the U.S. Air Force loaned him a plane to drop hay bales to starving cattle after a blizzard, Sig went along and helped push the bales out. Then he returned to Pierre and insisted on paying for use of the aircraft. "I believe that you pay your own way," he said. "We tried our level best to pay off the federal government."

Air Force personnel couldn't understand that logic, and didn't know how to accept the payment or where to put the money.

When you are governor of South Dakota, he said, people call you for just about any problem. After one heavy snowstorm, a Pierre area rancher called to complain that the county hadn't yet plowed his road.

"But it's absolutely, without question, the most challenging job you can have. It is the greatest thing next to being president of the United States," said Sig.

His views melded well with the rest of South Dakota. "I didn't believe in sin. I was pretty slow on drinking and gambling legislation."

That didn't make him a naysayer, however. He was an avid backer of building the dams on the Missouri River and worked to conciliate ranchers who would be losing land. He still remembers being at a hearing in Washington, D.C., when a prominent South Dakota rancher walked in with a stone and told the congressmen, "This is what they want to irrigate!"

He said there were also concerns about Indian burial grounds and many people were worried that the dams might break, causing even worse flooding than the river valley suffered without the project.

Of all the programs he worked on as governor, he cites the dams as the most important for South Dakota. Ranking a close second, however, is the fact that he stayed within a budget. "Spending within your means, that's an old Scandinavian trait. You always payoff your debts."

As governor, he retired the Rural Credit bonds owed by the state, created the Legislative Research Council, expanded the care of the mentally ill, accelerated the highway construction program, and terminated a 3 percent sales tax after it raised enough to pay World War II vets a soldiers' bonus. Not many states were rolling back taxes in those days of growth, and the South Dakota governor made headlines in the Wall Street Journal that day.

His happiest day of being governor, however, had nothing to do with taxes or dams or roads. It was Jan. 11, 1954, when he and Vivian had a baby girl, Kristin Karen. She was only the second child born to a governor while in office.

Kristin is now editor of the Brookings Daily Register, and friends say Sig’s house is stacked with copies of that publication. "I don't want to brag, but she is one of the best writers around," he says with a grin.

Upon completion of his governorship, Sig returned to Webster, hoping to get that law practice established at last, with an eye on maybe running for Congress. But President Dwight D. Eisenhower appointed him to the Federal Trade Commission and he and his family moved to Washington, D.C., without campaigning.

Sig held the FTC post for 10 years. He enjoyed the challenge of investigating anti-trust activities and laughs at how slow the process could be. "It took us years and years to get them to strike 'liver' off Carter's Little Liver Pills and make them call it what it is ... and we bad 300 or 400 lawyers under us!"

The Andersons promptly headed west to Webster when his second term was up. He made two other tries at elective office. In 1962, while still at the FTC, be sought the GOP nomination for the U.S. Senate after Francis Case died in office. He lost the nomination to Joe Bottum at a long convention, and Bottum ultimately lost to George McGovern.

Sig also sought the GOP nomination for governor in 1964, but lost to Nils Boe. At last, maybe he could really practice law. He was just getting started when Boe appointed him judge of the Fifth Judicial Circuit. At least that position allowed him to stay in Webster. He retired from the judgeship in 1975, and since then he has enjoyed retirement.

He has that law office near Main Street. And when his health allows, he's downtown every day. But be hasn't run any advertisements. Fact is, he says, "Webster always had plenty of good attorneys."

Editor’s Note: This story is edited from the May/June 1988 issue of South Dakota Magazine. To order a copy or to subscribe, call (800) 456-5117.

Comments