The Gift of South Dakota

Subscriptions to South Dakota Magazine make great gifts!

Subscribe today — 1 year (6 issues) is just $29!

The Wisdom of the Fool Soldiers

Feb 6, 2019

|

| A mural inside Scherr-Howe Arena in Mobridge painted by Oscar Howe depicts the Fool Soldiers rescuing captives during the Dakota War. |

In the winter of 1862, 10 Lakota warriors risked their lives and reputations for a novel concept: the rights of civilians during wartime. People called them "Fool Soldiers" because at a time when being indigenous made them targets, they staked a claim for militant humanism, even if it meant alienating some of their own. If they'd expected medals or accolades, the appellation may have proven apt. But the available evidence — the (mostly forgotten) stories told by descendants and historians — indicates another motive. They just wanted to "do good."

The Fool Soldiers' leader was a man named Charger, later Anglicized as Martin Charger, who was said to have proven himself in war, but who strove for peace, first in intertribal conflicts, then between Dakota/Lakota and the Euro-American arrivals.

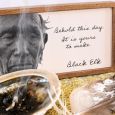

According to Samuel Charger's biography of his father, in 1860 a young man named Kills and Comes Back received a vision and approached Charger to discuss its meaning. The dream as related by Samuel Charger seems abbreviated, more like a postscript. He wrote that Kills and Comes Back, "had seen ten stags in his dream, all black and as he advanced toward them, one in the lead spoke to him. It said: 'This vision is to be fulfilled by you and to be complied with by all who are members. You and every member is to be respected and feared and you must be united in your undertakings.' As the dreamer looked closer he said he identified himself as the one who was speaking."

What did the black stag, who was Kills and Comes Back, show him(self)? Charger held a council to divine its meaning. "Kills Game afterward interpreted it to mean that the membership should be ten in number and that to be respected by the tribe, they should be generous, not only with food but with their property. Charger agreed as did all the others."

The following night, the young men shared the dream with Charging Dog, "a man of the same character as Kills Game, also a medicine man of fame throughout the tribe." Charging Dog reaffirmed the others' interpretation.

"As a medicine man I do not always get riches, but the good I do my fellow tribesmen is something to strive for. We may be brave in battle, but as everybody knows we do not live long and to do each other harm in our camp is very bad. I have seen a lot of it during my life. I believe the hardest thing for anybody to do is to do good to others, but it makes their hearts rejoice."

|

| Four Bear, a member of the Fool Soldiers band. |

So they organized a Society based on those principles. In August of 1862, Dakota people at Upper and Lower Sioux Agencies of Minnesota were brought to the brink of starvation. They'd been hit by famine, and the annuities the government owed them were late, when agency storeowner Andrew Myrick was reputed to say, "If they are hungry let them eat grass or their own dung." Myrick was killed on the first day of the Dakota War.

You know how the lines blur if you've been there, and what happened next. Civilians killed. Reprisals that kill more innocents. That's how it was going on August 20, when a band led by White Lodge attacked the tiny settlement of Lake Shetek, near present-day Currie, Minnesota, killing 15 settlers and taking eight captives — two women and six children.

When news traveled to Charger and the Fool Soldiers that White Lodge and his band were camped, with their captives, on the west side of the Missouri, they saw an opportunity to live their commitment to the vision.

They left their camp near Fort Pierre, traded horses and pelts for food they could offer as ransom, and set out for White Lodge's camp. As they crossed the river, people were said to implore them not to go. "They thought the 'boys' as they called them, would not come back alive," wrote Samuel Charger, "and the undertaking was foolish. But Charger told the crowd 'there is only one life and that is short, hence we should do what we think is good.'"

According to South Dakota historian Doane Robinson, the band included: "Charger, Kills and Comes, Four Bear, Mad Bear, Pretty Bear, Sitting Bear, Swift Bird, One Rib, Strikes Fire, Red Dog and Charging Dog." Along the way, they encountered a Yanktonais camp, where they were told that White Lodge's Band was camped near present-day Mobridge.

As the stories tell it, White Lodge did not warmly welcome the Fool Soldiers. Negotiations were tense, and could easily have degenerated into shooting. In the end, White Lodge's son, Black Hawk, agreed with the Fool Soldiers and helped them secure the hostages — the two women and five children, one child had died — but they weren't victorious yet.

They'd had to trade away all their horses and provisions, and had a 100-mile journey ahead, through blizzard conditions with a group of ragged, hungry children. As they started back, they received some help from Don't Know How, a Yanktonais man who may have traveled with them to White Lodge's camp, or met them coming and going. He furnished them with one horse and helped them fashion a travois to carry the children. (Don't Know How was the paternal grandfather of the great Dakota artist Oscar Howe, who depicted the Fool Soldiers' rescue of the Lake Shetek captives in one of his murals at the Scherr-Howe Arena in Mobridge.)

Don't Know How's kindness helped, but the Fool Soldiers still had to complete a journey akin to Washington's crossing of the Delaware to make it home. Seeing that Laura Duley, one of the two adult female captives, was barefoot, Charger is said to have given her his moccasins, wrapping his own feet in old clothes.

The group camped only twice, walking through the third night, arriving the next morning at the river, where several traders helped them make a treacherous ford of the river, which wasn't wholly covered with ice. From there, a trader named Charles Primeau housed the freed captives until the U.S. Army returned them to their relatives.

|

| A monument recognizing the Fool Soldiers stands in Mobridge City Park. |

Then the Fool Soldiers' story faded into obscurity. They had set out to do good and succeeded. If they'd harbored any less selfless motives, they'd have failed.

Fool Soldier Joseph Four Bear didn't benefit from his actions, says his great-granddaughter Marcella LeBeau.

"He signed the peace treaty [Treaty of Fort Laramie, 1868], and he had to live on the northeast corner of our reservation and not leave. If he left he'd have to have a signed permit to come and go, otherwise he would have been shot as a hostile. They gave him land allotments on the reservation. That was already our land. That was treaty land. What kind of sense is that, to give back his own land to him, and he had to live there?

“And he had to live by that peace treaty. So he didn't dance Indian. He didn't follow his own ways. He didn't hunt for his people and provide for them like he did in the past. So my thought is: if you can't be who you are then who are you? So he lived out his life like that."

Were the Fool Soldiers misguided in helping the captives?

"I believe they did a good deed," LeBeau says.

Joseph Four Bear did receive a token of posthumous gratitude.

"On his tombstone, a white marble tombstone, it said something about: He was a friend to the white man for over seventy some years," LeBeau says. "And I know that his own people didn't have the funds to do that."

There is also a modest quartzite marker in Mobridge City Park that reads: SHETAK [sic] CAPTIVES RESCUED HERE NOVEMBER 1862 BY FOOL SOLDIER BAND.

In 1996, Paul Carpenter, a descendant of one of the rescued captives, brought gifts to the descendants of the Fool Soldiers and honored them in a ceremony. "There was standing room only in that building," LeBeau says.

People lined Main Street and reenacted scenes from the rescue — Martin Charger giving Laura Duley his moccasins, wrapping his feet in rags, the children transported by travois, pulled by their single horse.

The tribute, 134 years after the event, raised some awareness momentarily.

"I think in school they should learn about it," LeBeau says. "But I don't think that's happening. I know when I went to the boarding school we didn't learn anything."

The Fool Soldiers were revolutionaries. While their own people were steadily losing their land and way of life, they took a stand for people who looked like the enemy, 87 years before the Fourth Geneva Convention codified civilian wartime rights — including a prohibition on taking civilian hostages — into international law.

The reasons they haven't been recognized probably range from the obvious (they were Native American) to the thornier issue of their acceptance within their own group. "Their own people — some of them — were against them," LeBeau says.

The Fool Soldiers may be perceived, by some, as capitulators, and any recognition of them may, in kind, be seen as an exclusive endorsement of their response to the times in which they lived, like the epitaph on Four Bear's tombstone. Their act, though, is not a negation of the survival strategies of warriors like Crazy Horse or Sitting Bull. Rather, it was the antithesis of Custer's attack on civilian camps, or the massacre of disarmed noncombatants at Wounded Knee. The Fool Soldiers have been called pacifists, but Samuel Charger's biography of his father depicts them not as pacifists but warriors turned militant humanists.

Martin Charger and his men are the moral forebears of Hugh Thompson and the American GIs who stopped the massacre at My Lai (and others like them). Decades later, Thompson and his men got their medals. On March 16, 1968, they didn't know if they would make it out alive. That's how it's always going to be for a Fool Soldier. The conventioneers can call for Twister as a means of conflict resolution if they want. Wartime ethics live or die on the barrel side of White Lodge's (or William Calley's) guns. What the nations codified on Lac Léman, the Fool Soldiers lived on the Mni Sose. There are greater monuments to lesser men.

Michael Zimny is the social media engagement specialist for South Dakota Public Broadcasting in Vermillion. He blogs for SDPB and contributes arts columns to the South Dakota Magazine website.

Comments

As I grew up, I learned from the words and actions of people around me the negative stereotypes my relatives and neighbors held against the Native race.

When I went to college, I decided to reject those prejudices and found out it was a lot harder than I thought. SDSU is where I learned of Oscar Howe and is incredible gifts. That’s when it occurred to me that those murals in Mobridge were special.

This article is the first time I’ve learned of the full story behind one of the murals, and I was moved by the spirit of peace embodied in the artist’s telling of this historic event. And I’m struck by the courage of the Fool Soldiers, especially when they were painfully living out injustices wrought by the new Americans.

As one of those new Americans, my world view sees the story as another culture taking a risk to save people of my culture. But the author of this article makes it clear that this was no “act of heroism, as we think of it today.

The “military humanist” view makes clear that the motive of the Fool Soldiers was entirely altruistic, and that it was contrary to the opinion of their own neighbors and relatives.

This is a well-written recounting of history, with Howe’s mural as the touchstone. A piece of history that needs to be not only acknowledged but also lauded! No history of our region and nation is complete without it.

They returned to their tribe and confessed what they’d done to the chief. The chief said,”we are all going to pay for this so instead of asking forgiveness, let’s form war parties and kill the rest”. They raped, pillaged, killed, burned, and stole. The US government caught them and removed them all from Minnesota. Most of the hanged Santee went to the gallows on the accusations of a former slave who went with them. The Santee said he was one of the worst but on account of the ongoing war, the government felt that it couldn’t hang a black man, guilty or not. They did hang an innocent white man though.

"The massacre began as a result of misbehaving Santee youth, not starvation" what a disgusting and completely irresponsible take during the real beginning of the end for the Dakota Isanti, Mdewakanton, and other tribes who had lived in the Minnesota River Valley for over 10,000 years. "They raped, pillaged, killed, burned, and stole. The US government caught them and removed them all from Minnesota." Even if that were true (every piece of history in regards to that accursed "War" was written by truly unbiased white men - the victors write the tales), just who do you think they learned it from? Certainly they warred amongst themselves, but the art of kanly was noble, symbolic, and respectful. White people brought their savage weaponry, rape, disembowelment, scalping, beheading, and disease as the law of the land. How else could they depopulate millions of Natives across the Americas in only 4 centuries? And the only way to survive against such tactics were to adopt them themselves. Just ask the Mujahideen during the Russian invasion in Afghanistan. The white arrogance to so blatantly set up their fort and farms and towns right in the middle of Dakota cherished lands. Did they expect them to just give it all up in return for nothing? While their children starved?