The Gift of South Dakota

Subscriptions to South Dakota Magazine make great gifts!

Subscribe today — 1 year (6 issues) is just $29!

Strong Values, Strong Hearts

Sep 25, 2012

Editor’s Note: This story is revised from the November/December 1995 issue of South Dakota Magazine. To order a copy or to subscribe, call 800-456-5117.

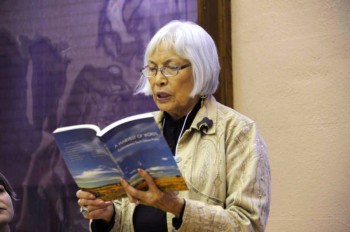

Writing and teaching has been the lifework of Virginia Driving Hawk Sneve, a Brule Sioux who grew up on the Rosebud Indian Reservation. Her literary achievements have garnered more attention than her classroom pursuits, but in both roles she has labored to cast a positive light on the differences between Native Americans and other races.

Sitting Bull, the great Sioux chief, was quoted as saying, "I have advised my people when you find anything good in the white man's road pick it up but when you find something bad or that turns out bad drop it. Leave it alone."

Sneve's philosophy mirrors that quote. But she encourages her people to also recognize what is good in their own heritage. Sneve realized years ago that the strong values of Indian life were seldom revealed in stories of their culture — especially those family strengths which came under siege during the last 100 years of cultural integration in America.

When her daughter, Shirley, was reading books by Laura Ingalls Wilder in the early 1970s, she asked if the Sneves had lived the same experiences as the Wilders. Before she answered, Virginia read the books herself and discovered that the only reference to Indians spoke of "naked wild men" with horrible smells and bold, fierce faces. She then read other children's literature and found similar treatment of her ancestry. Some stories told of brave young warriors and beautiful princesses but there were few stories that revealed the real-life strengths of the Indian culture and no stories of modern Indian children.

Sneve, who had been trying to write for adult women's magazines, decided to try her hand at children's stories. Her first, Jimmy Yellow Hawk, was a book about a little Sioux boy who wants to change his name. She wrote of his concerns in the contemporary world and the cultural reasons for Indian names. The book won a national competition for minority children's books in 1972. That started Sneve on a career as a children's author.

"It has been emotionally rewarding," said the soft-spoken Sneve when we spoke with her in 1995. "I get letters from children who have criticisms or suggestions. Sometimes they have ideas for better endings. And they can be very blunt."

But obviously not so blunt as to discourage her. Since the success of Jimmy Yellow Hawk she has written more children's books and numerous short stories that have appeared in Boy's Life and other publications and collections.

She has gained a reputation, both in Indian country and the literary community, as a first-rate storyteller. "Virginia is a good example of an elder in the traditional sense of the word," explained Chuck Woodard, a professor of English at South Dakota State University in Brookings and longtime friend. "She's a careful observer of experiences, and she has learned, not only from her own experiences but also of her people, which is one and the same in a tribal sense."

Woodard said Sneve's ability to imagine is a key to her writing. He said her 1995 book, Completing the Circle, "is a culmination of her lifelong reflections of what it means to be tribal. She uses both recorded events and her own imagination — developed by decades of examination and reflection."

Sneve's daughter, Shirley, saw signs of mom's imagination when she told bedtime stories to her and her brothers, Paul and Alan. "She made up this series of episodes to get us to take a nap. I remember a witch named Helen and some other characters. But back then she left the Indian stories to my grandparents."

Grist for Sneve's stories is gleaned from her experiences growing up on the Rosebud Reservation. She attended BIA day schools and graduated from St. Mary's High School for Indian Girls in Springfield. She then studied at SDSU in Brookings, graduating with a B.S. in 1954 and a master's in education in 1969. She taught at schools in White, Pierre and Flandreau. When she retired as a teacher and counselor at Rapid City Central High School in 1994, it freed more time for writing.

Sneve sees her writing as an extension of her work as a teacher and counselor — and as a means to give an accurate portrayal of her ancestors' lives on the Northern Plains. But Sneve doesn't lecture. It's not her style. She weaves a lot of legends and true family stories together with facts.

Her explorations have taught her much of the strengths and weaknesses of Sioux culture from the female point of view. "I was amazed at the tenacity of the women and how they held the family together. They had so many trials in their lives, especially in the last 100 years, but they still managed to survive and rise above those trials and not give in."

She has noted that most literature is written from a male perspective. That is especially true in the case of the American Indian. "Male historians used male sources (missionary, military men and fur traders) in narrating their Sioux histories and those sources reported few events involving the women of the tribes, rarely even noting their names. Yet Indian women really had more of a say of what went on in tribal affairs than anyone on the outside realized," said Sneve.

The Sioux felt women had a near-mystical power because they could give life. "The tribes realized they bore the children and if there were no women the tribe could not survive." She discovered a quote from Standing Bear in 1931 who said, "Women and children were the objects of care among the Lakotas and as far as their environment permitted they lived sheltered lives. Life was softened by a greater equality. All the tasks of women — cooking, caring for children, tanning and sewing — were considered dignified and worthwhile. No work was looked upon as menial, consequently there were no menial workers."

Virtue, modesty, hospitality and devotion to family were highly valued and young girls were encouraged to act appropriately and not bring shame upon the family. Pride in appearance and skill in the womanly arts were also important.

When white men first arrived on the plains, women who cohabited with them brought honor to their families and tribes, according to Sneve. But such marriages often resulted in drudgery and isolation for the Indian woman and if her husband became abusive she did not have the family support she would have had within the tribe.

Mixed-race marriages later became even more difficult. The Driving Hawk and Sneve family trees include such marriages. While they have been successful, Sneve has obviously pondered the dilemmas faced at times by both whites and Indians.

In 1977 she wrote a short story called "Grandpa Was a Cowboy and an Indian." Here is an excerpt:

First I thought I'd stay out of it but after fists started flying, I jumped in. The first guy that swung at me was a white man so I hit back and was helping the Indians. I thumped away at my white friends till in the confusion an Indian got me in the gut. Now that made me mad. Here I was on his side and he slugged me. I gave him a good one back and then I was fighting Indians. I ended up getting whopped good by both sides and never did make up my mind which bunch I belonged with.

All the conflicts of the Indian culture — both from within and from the outside — caused much disruption in the lives of the Dakota people, said Sneve. "The fact that any families held together is pretty amazing."

She thinks her own family did well, "because of the values that were passed down from the generations, particularly among the women. Family was important. We took care of one another."

Those values are still alive today. "Indian women have become more politically active," Sneve said. "I don't think Indian women are so much feminists. They are not as concerned about women's issues as they are about tribal issues and the issues that affect all of their people."

Woodard, the English professor, said Sneve's 1995 book represented "a strong affirmation of the values of Dakota women. It shows what powerful models they have been of integrity, courage, humor, storytelling ability and resilience."

Somewhere between the lines there may also be a call to action, woman to woman, It's not a loud bugle call — just a gentle lesson of how life was and how we all might learn from the past.

Virginia Driving Hawk Sneve Today

Sneve has continued to write since this article was published in 1995. Her most recent book, The Christmas Coat: Memories of my Sioux Childhood appeared in 2011. She has received many honors for her work, including the 1992 Native American Prose Award and the Spirit of Crazy Horse award in 1996. In 2000, Sneve was the first South Dakotan to receive the National Humanities Medal.

Watch for Sneve at the 2012 South Dakota Festival of Books in Sioux Falls. She will be presenting “Lakota Storytelling” and hosting a Q&A after the Lakota Berenstein Bears screening on Saturday.

Comments

if possible------ phone---e-mail --address------